Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences

Department of Circulation and medical imaging

Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences

Department of Circulation and medical imaging

by

Asbjørn Støylen, Professor, Dr. Med

asbjorn.stoylen@ntnu.no

![]()

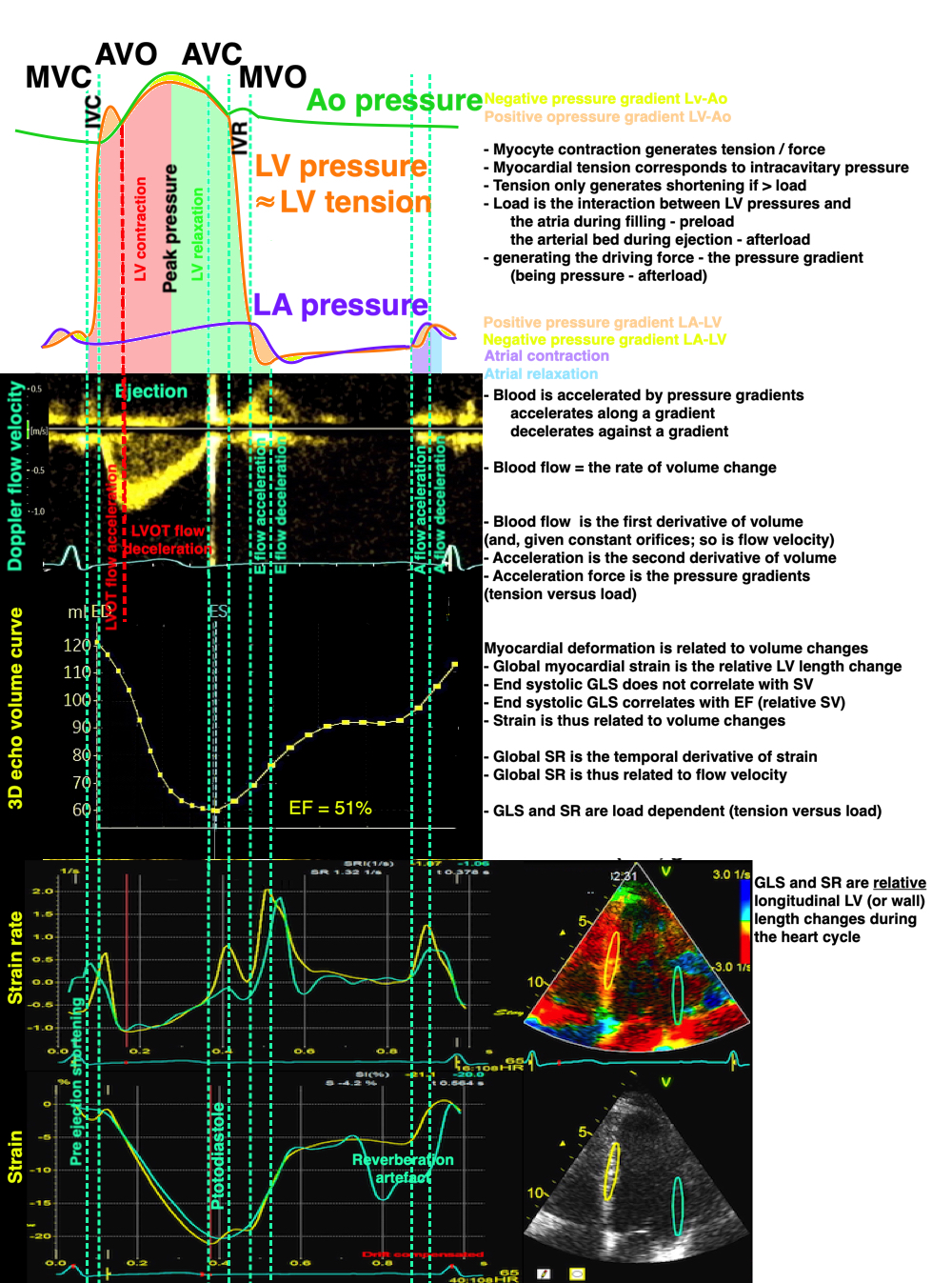

Deals with the basic physiological concepts; contractility and load, and the relation of deformation parameters to these, diastolic function, event timing and relation to valve function and intraventricular flow and pressures. Any imaging method deals with myocyte shortening, myocyte shortening is always a function of tension versus load, and thus any imaging method and measure is load dependent.

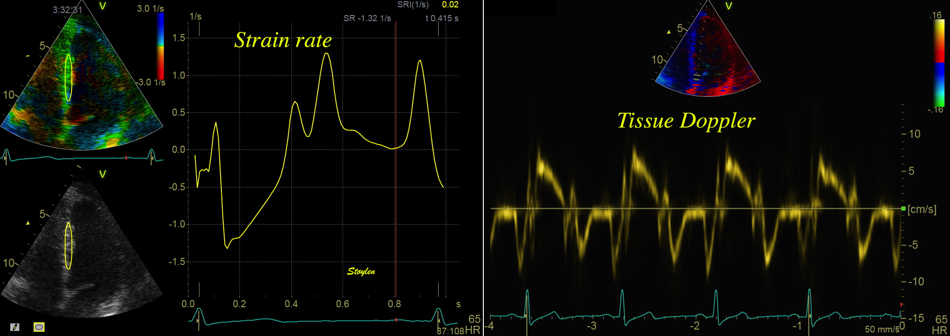

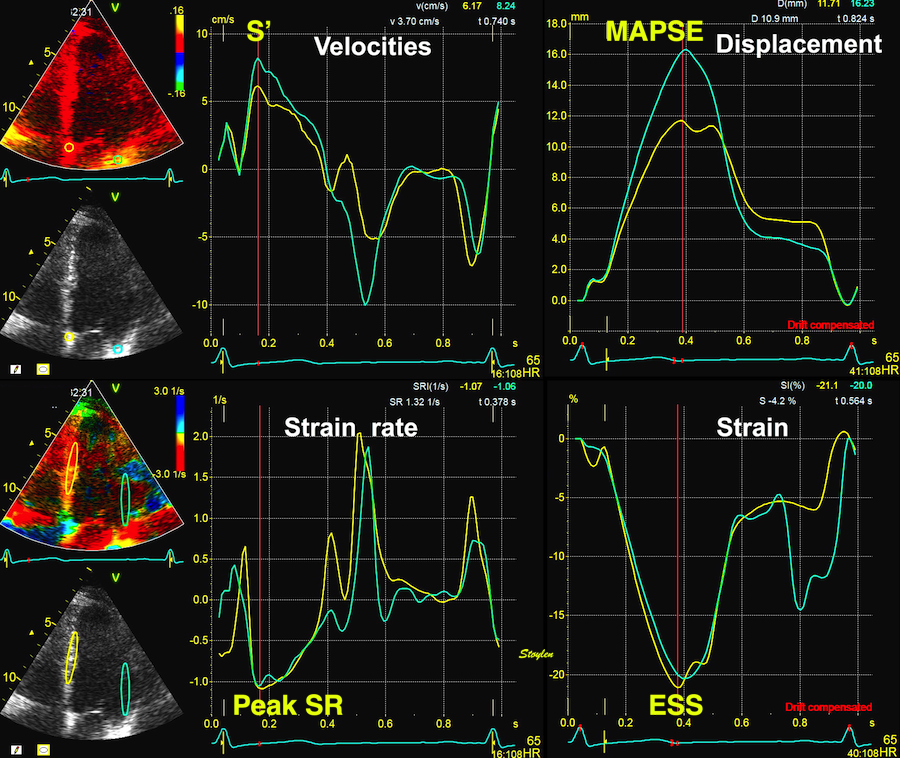

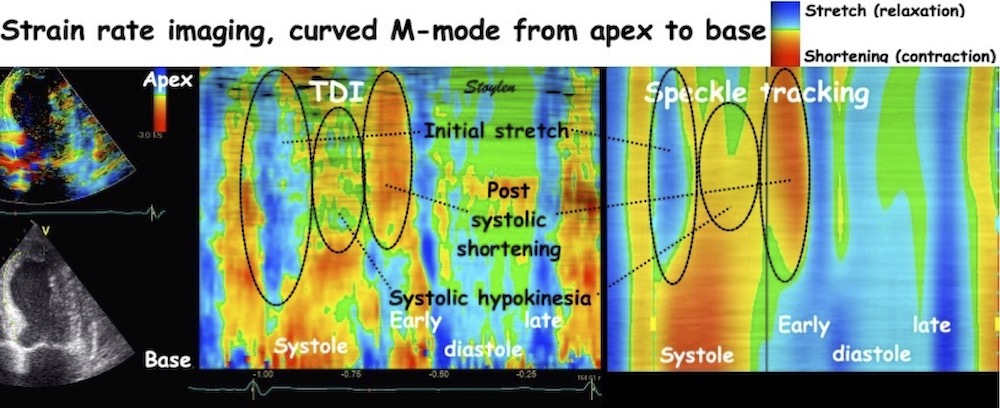

There are two methods for ultrasound deformation imaging, tissue Doppler and speckle tracking. Both methods have advantages and disadvantages, which are dealt with in the ultrasound chapters, but the basic physiology is method independent, so the basic physiology in this chapter is valid for both methods.

This section deals with the basic physiology as seen with various echo methods, and replaces most of

In the physiological aspects, as these were largely overlapping anyway.

There will be discussions of validity on composite measures, these will be based almost solely on physiological principles.

Of course the opposite caveat is also true. Biological plausibility is not evidence of effect, it's at bes hypothesis generating.

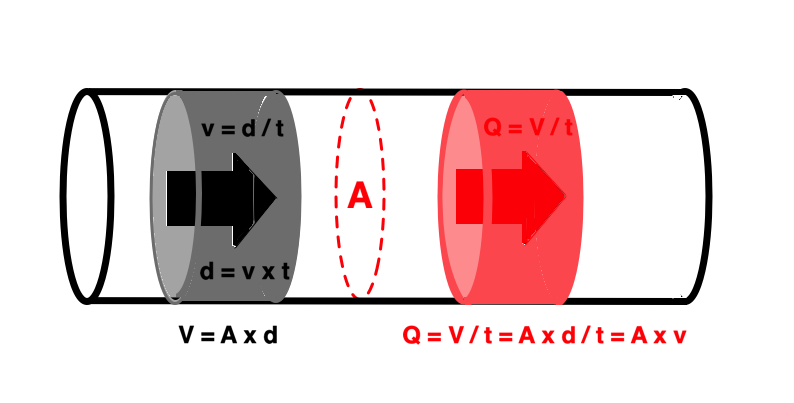

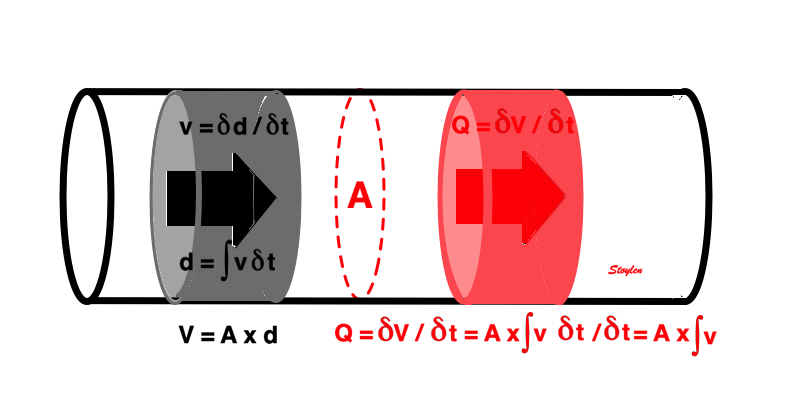

The first temporal derivatives of these parameters are

The spatial derivative of flow is

This is

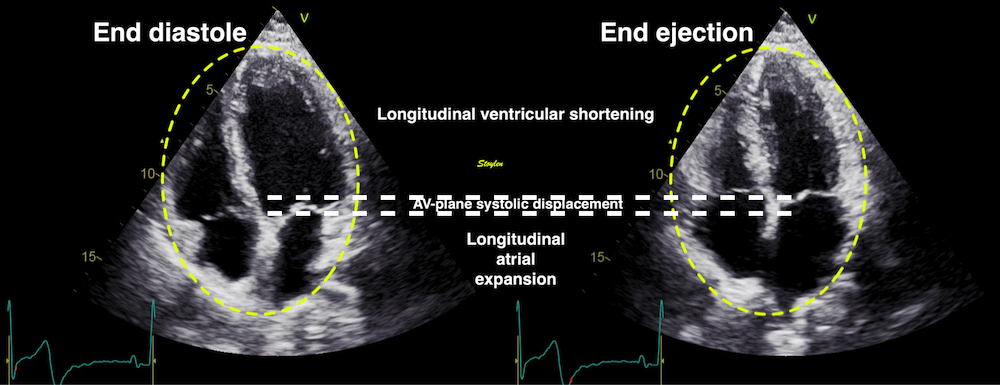

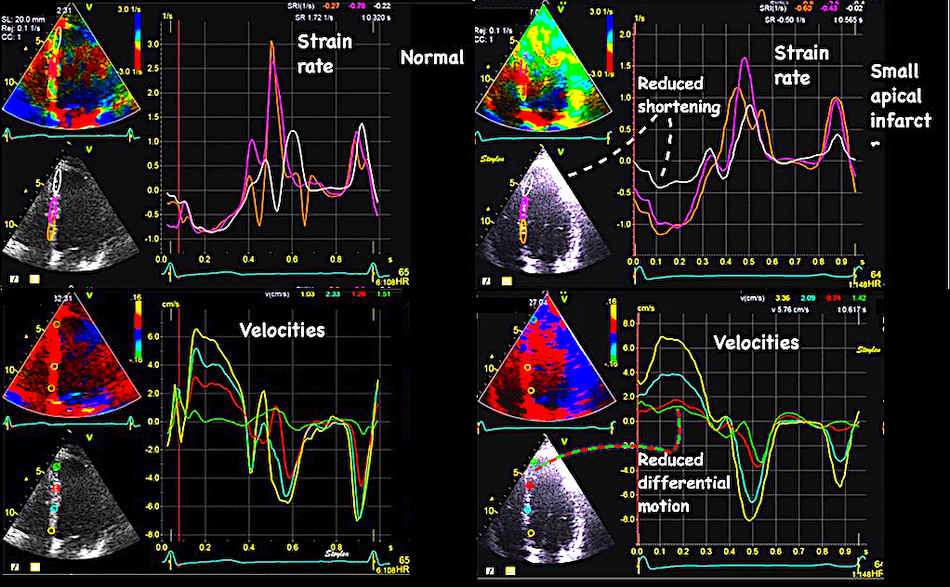

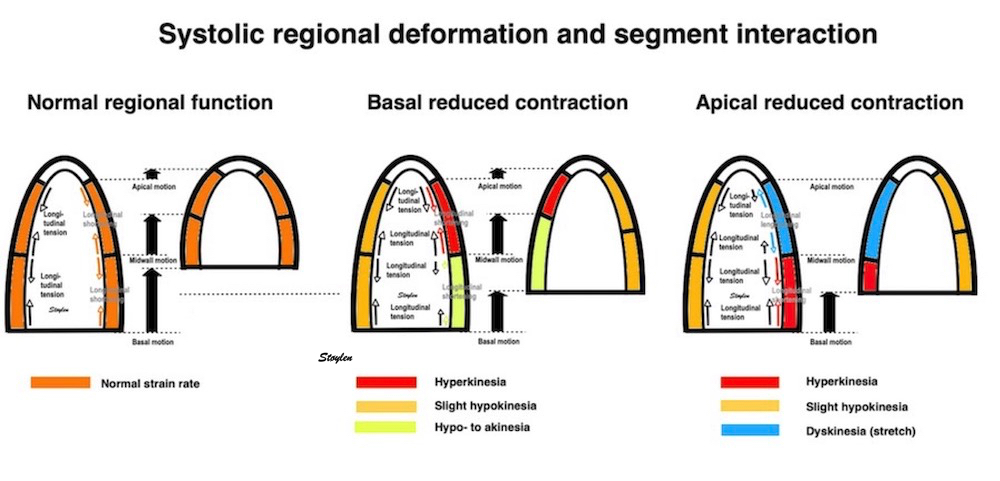

Systolic deformation is the result of fibre shortening, although in a complex manner.

| |

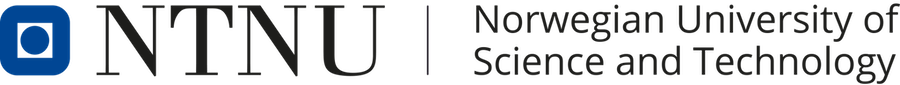

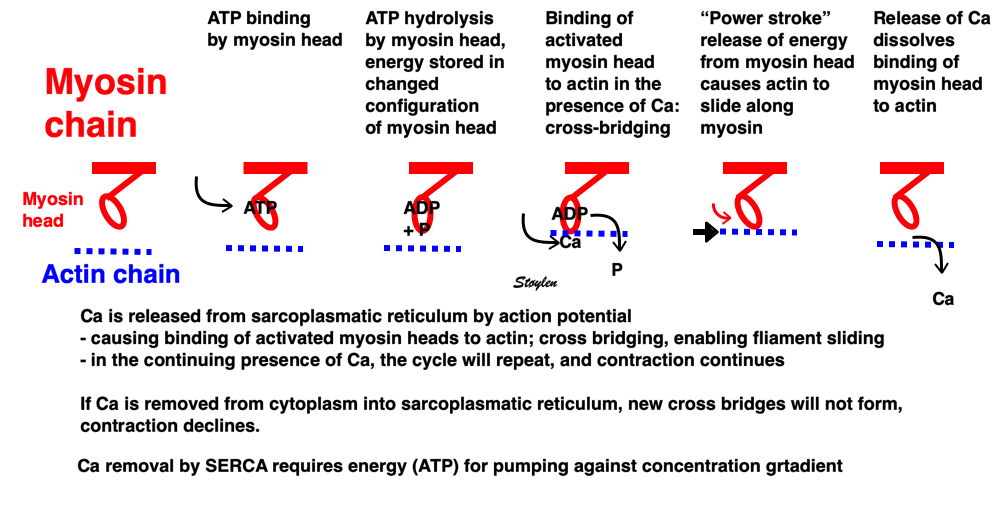

Image of beating isolated myocyte, prepared so the cell fluoresces with the presence of free calcium in the cytoplasm, the cell is stimulated to generate action potential. In systole the cell can be seen to increase free calcium and simultanously shorten. In the cellular diastole, the cell can be seen to elongate, and simultaneously free calcium disappears from the cytoplasm. The isolated myocyte is the completely unloaded situation, where myocyte tension results directly in shortening, and where shortening is a direct measure of contraction.. Image courtesy of Ph.D. Tomas Stølen, cardiac exercise research group (CERG), Dept. of Circulation and Medical Imaging, Norwegian University of Science and technology. | Excitation-tension diagram. The Action potential triggers the influx of calcium, which triggers further release of Ca2+from sarcoplasmatic reticulum. Calcium binds to troponin, and allows activated (by ATP) myosin heads to bind to troponin sites on actin (cross bridge forming) and release energy, causing the filaments to slide along each other, as long as there is a high calcium concentration in the cytoplasm. As the cell membrane repolarised, this triggers the removal of calcium from the cytoplasm, mainly by the SERCA pumping it into the sarcoplasmatic reticulum again. The removal of free calcium is an energy (ATP) demanding, active transport of calcium into the sarcoplasmatic reticulum by SERCA.Thus, obviusly, both contraction and relaxation are ATP demanding processes, and energy depletion will affect both. |

Fibre shortening is not the same as contraction. We have both isometric and isotonic contraction:

Diagram of mucle sarcomere shortening. Shortening is the result of tension versus load. If the load is higher than the maximal tension the muscle can develop, the muscle will not shorten at all. Actin is still moved along the myosin , but the energy is stored as deformation within the sarcomere without shortening aof the sarcomere. This means that the force generated by contraction is stored as elastic tension in the muscle, and the contraction is isometric The middle figure, retaining the length of the baseline - left). If the load is less than the maximal tension, the muscle will start to shorten when tension equals load, and from there the contraction is isotonic - shortening at constant load. The right sarcomere is shorter than the baseline.

In physiology and pathophysiology, the main object in characterising increased or decreased muscle function is the contractility, which is the ability to develop tension independent of load. As imaging only measures length, the tension must be inferred from knowledge of load. Shortening is the result of tension vs. load as discussed later.

As the muscle uses some time to develop full tension, in most situations there will be a period before tension reaches load (an isometric phase) before tension equals load and the muscle starts to shorten (isotonically) (78).

The concept of load is important for understanding the contractility. Contractility is defined as the inherent capacity of the myocardium to contract independently of changes in the preload or afterload (79).

The preload is defined as the load present before contraction starts (79). This is illustrated below left.

Frank-Starlings law of the heart states: Dilatation is caused when increased venous return or decreased ejection increases end-diastolic volume. This form of dilatation, within physiological limits, increases the heart’s ability to do work. The stroke volume of the heart increases in response to an increase in the the end diastolic volume, when all other factors remain constant. (83)

Preload is the force acting on the muscle before contraction starts. Thus, it will stretch the muscle, and induce an increase in muscle tension. This is best explained in isometric experiments, where an isolated muscle is fixed in both ends , and tension is measured by a tensiometer.

|

|

Isometric experiment. Isolated muscle with fixed length, tension measured by a tensiometer. The three measures of tension are the peak rate of force (tension) development, time to peak tension and peak tension. They are all measures of contractile function. | Adding a weight to the muscle without stimulating contraction, will stretch the muscle, before fixating the muscle and adding a tensiometer. This can be achieved without the weight, of course, simply by fixing the muscle at different lengths (pre stretch). |

With increasing length by pre stretch, the stretch will both increase passive tension (elasticity), but also increase the active tension developed when stimulated (78).

|

|

Stretching the muscle before stimulation, increases tension. The increase in passive tension will be present at rest, before twitch. During twitch, there is an increase in total tension with increasing pre twitch length. The increase in contractile tension is then the difference between the passive and the total curve. | Isometric twitces with increasing pre-twitch length. In can be seen that as opposed to inotropy, time to peak tension do not increase, even though peak tension does, and, as a consequence of this the rate of force development (as the rise to higher peak during the same time gives higher rate). |

|

|

Hypothetical length tension diagram, based on the sarcomere hypothesis, that by increased fibre length initially will increase the overlap between the myosin head regions and the troponin regions on actin, optimising the number of cross bridges that can be formed, and thus the peak tension obtainable. In this model there is an optimal length, then the available number of cross bridges, and thus the peak tension decline again. | Both shortening and shortening velocity can be seen to increase with increasing preload. |

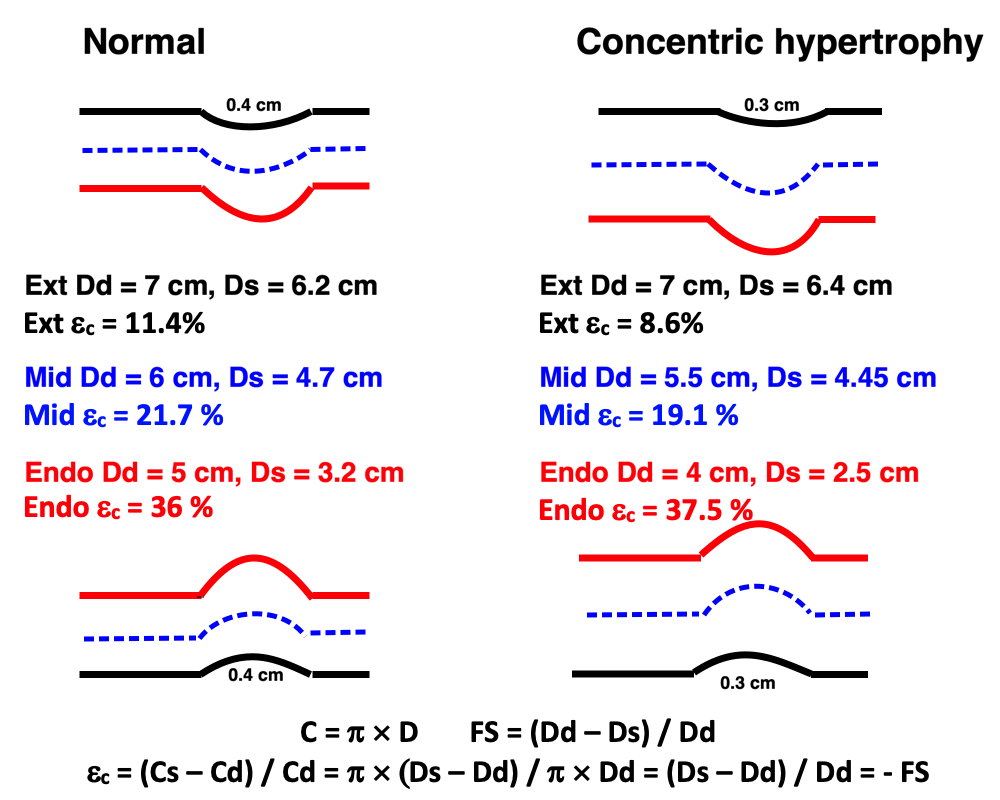

Afterload is force added to the preload as resistance to the muscle shortening. Total load is preload + afterload. This is the force the muscle must overcome ( e. the tension the muscle must develop) in order to shorten, also termed wall stress. This can be expressed as wall stress, the force acting on the wall. This is proportional to both the intracavitary pressure, and radius. Wall stress, however is the tension per cross sectional thickness of the wall, i.e. if the same load is applied to different wall thicknesses, the thickest wall has lowest wall stress per mm thickness.

This is summed up in Laplaces law: Wall stress () is proportional to pressure (P) x radius (r), and inversely proportional to the wall thickness (h):

![]()

In an afterloaded contraction, the muscle must first build up force corresponding to the total load, before it can start shortening. When the force equals the load, further contraction is translated into shortening without tension increase (isotonic contraction). Thus, neither peak force nor time to peak force are relevant measures of contractility.

|

|

The difference between pre- and afterload is illustrated here. After preload is added, a support is placed, preventing further stretch of the muscle when another weight is added. This second weight is the afterload. When the muscle contracts, it has to develop a tension that is equal to the total load, before it can shorten. If the peak force is higher than the total load, the muscle will then shorten without generating more tension, in an isotoniccontraction. | Isotonic isometric twitches tension diagrams above, length diagrams below. From the diagrams, it is evident that shortening only starts after tension have reached load, and then, the tension is constant while the muscle shortens. Thus the first part of an unloaded contraction is also shortening, while the first part of a loaded contraction is isometric, becoming isotonic after tension equals load. Peak rate of force generation (RFD), occurs during the isometric phase (except in the unloaded phase, where there is no tension development). Peak rate on the other hand occurs during the first part of the shortening, after tension = load, and is thus later than peak RFD. The figure also shows that shortening decreases as load increases, as more of the total work is taken up in tension development. This experiment shows that both peak rate of shortening and peak shortening, i.e. peak strain rate are affected by afterload. Both peak shortening and peak rate of shortening are affected by pre- and afterload.The curves are explained further below. |

|

|

|

Length tension diagram of a muscle twitch in an isolated muscle preparation. The muscle takes some time to develop the tension that equals the load, and during that period the contraction is isometric, with no shortening. Shortening starts when tension equals load. When the muscle relaxes, relaxation induces shortening until tension again equals load, after that relaxation is isometric. | Series of twitches with different loads. All twitches follow the same tension curve, i.e. shows the same contractility, but as load increases, shortening starts at later time points, and the shortening time as well as the extent and rate of shortening decrease. | Series of twitches with the same load, but with different contractility (ability to develop tension). With decreasing contractility, it takes longer to develop tension = load, the period of shortening as well as the extent and rate of shortening decrease. |

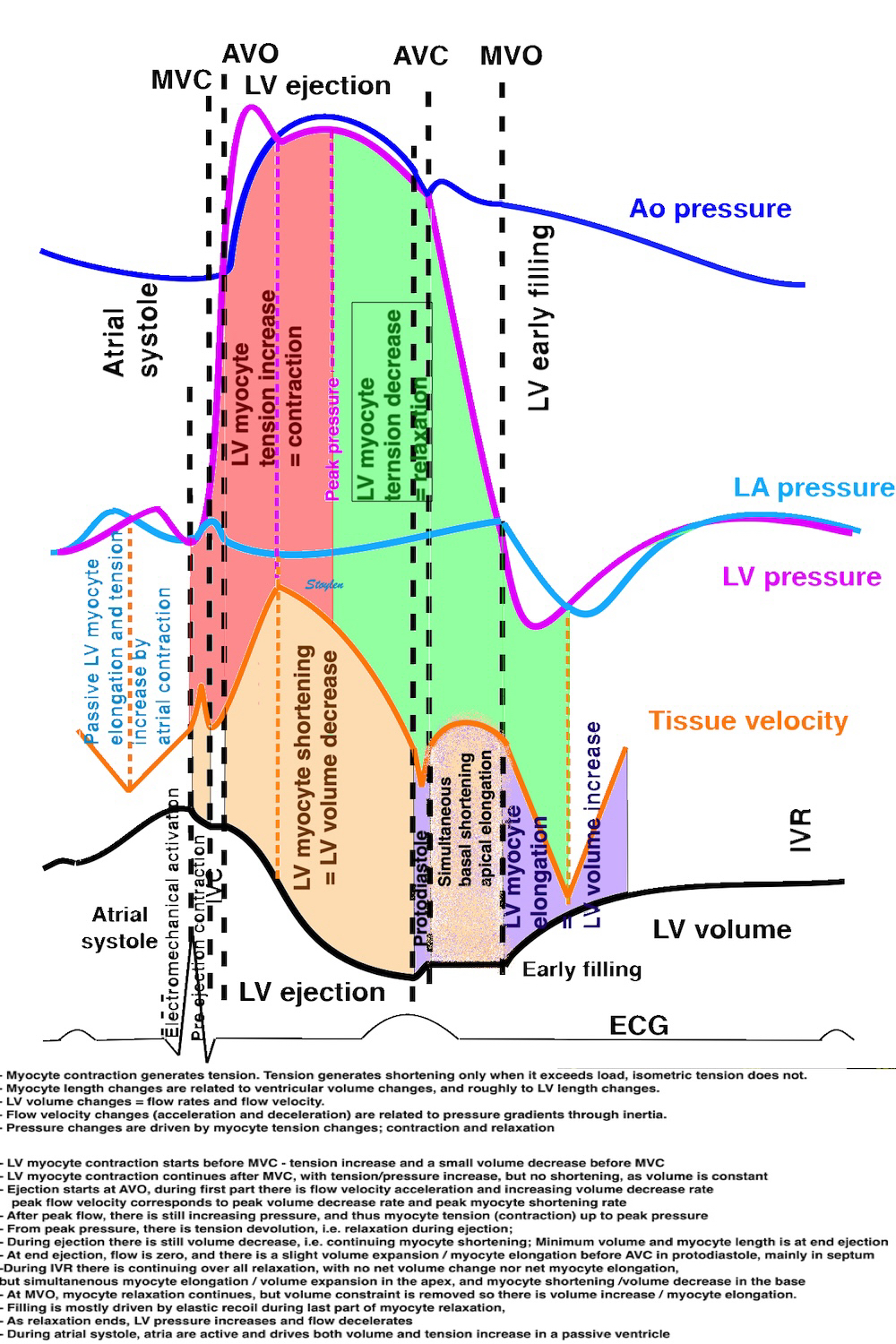

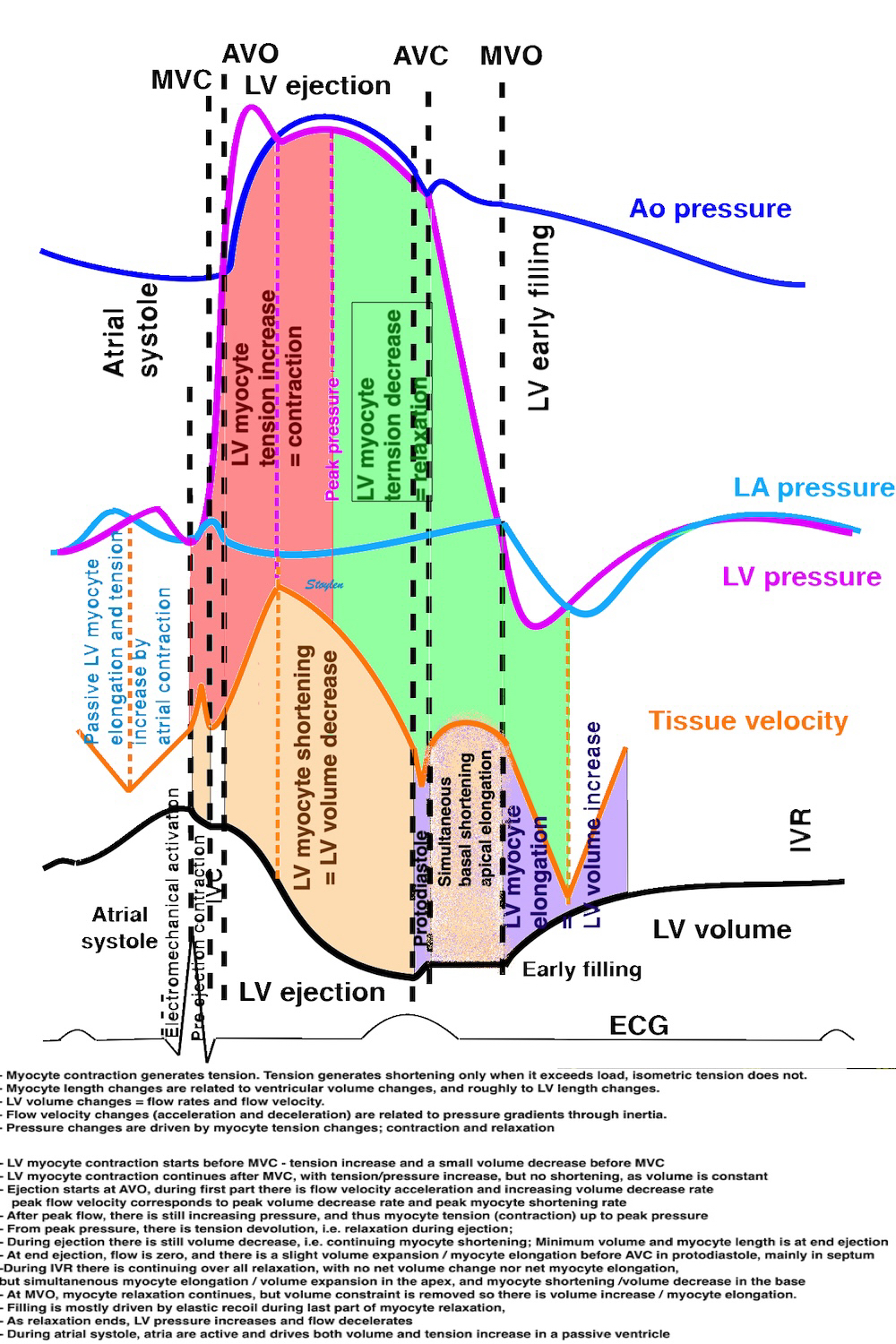

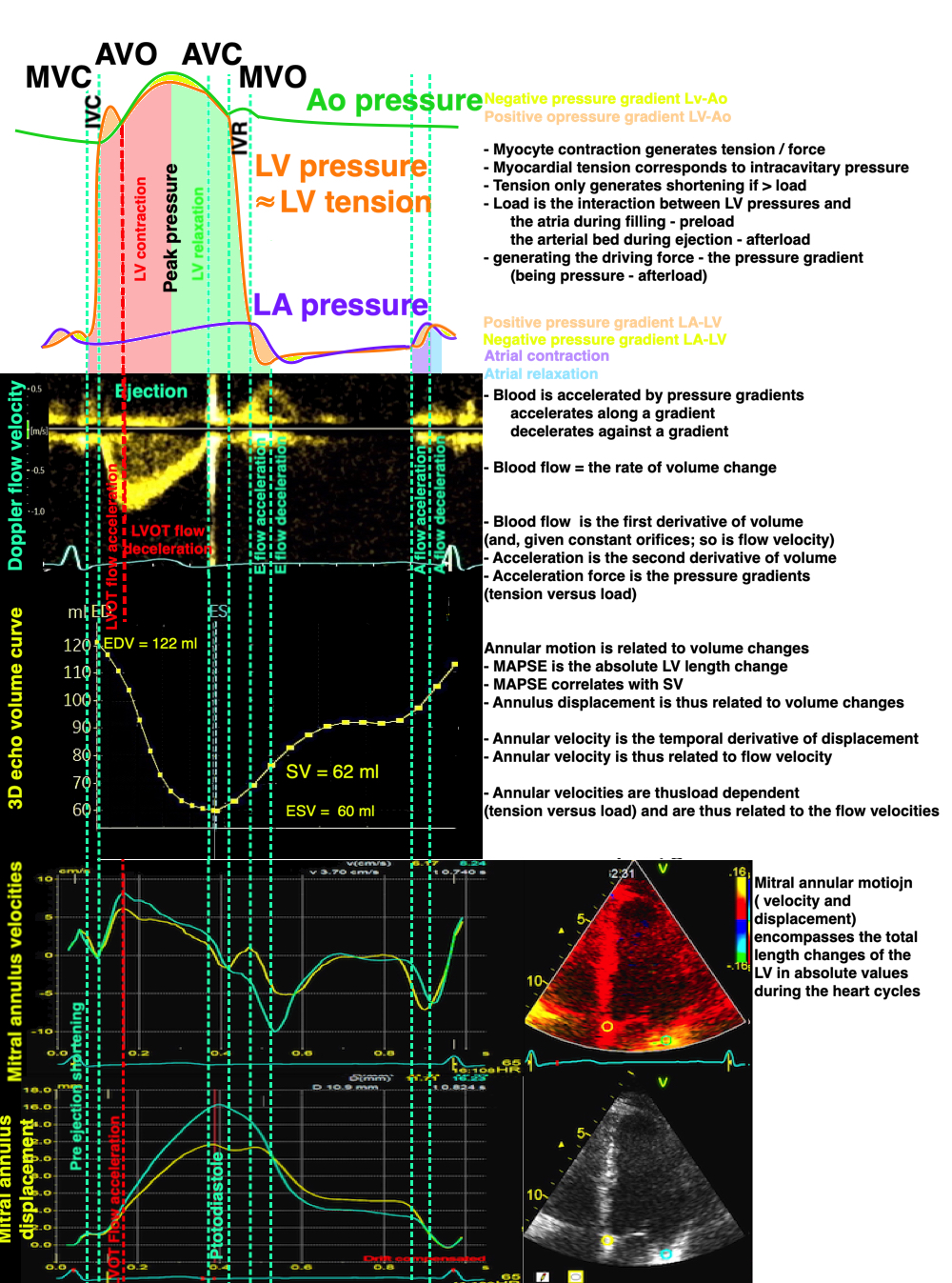

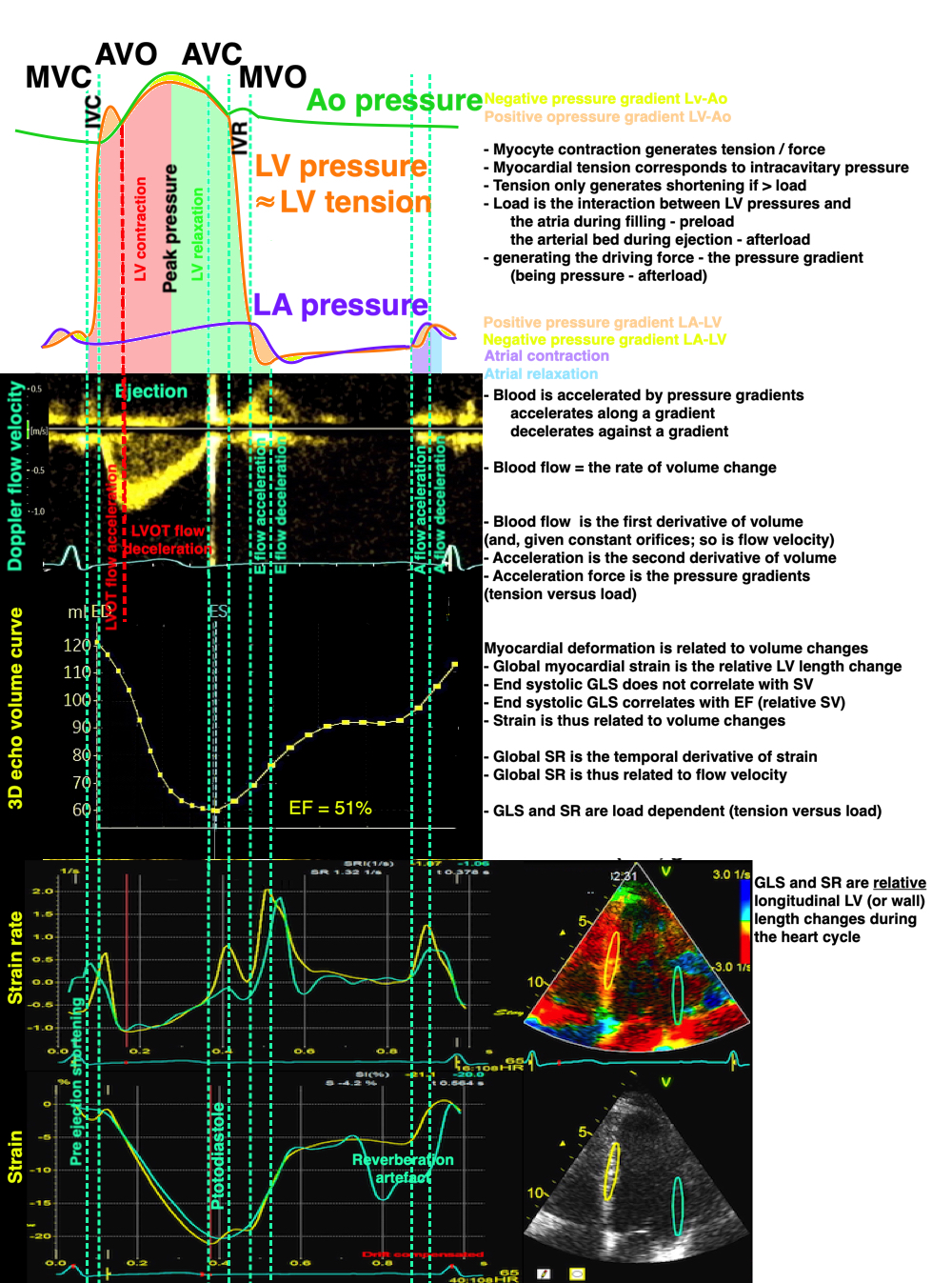

Looking at the whole heart cycle, there is a complex interaction between tension increase and devolution, and shortening and elongation whioch is discussed here.

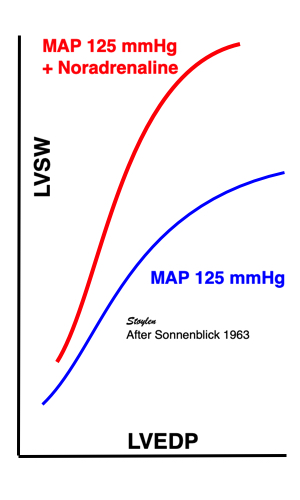

Contractility is defined as the inherent capacity of the myocardium to contract independently of changes in the preload or afterload (79). The contractility decreases in myocardial failure and with betablocker, but increases with inotropic stimulation, such as adrenaline, noradrenaline or calcium.

|

|

Shortening velocity and total shortening, Relation to preload and total load. Both shortening and velocity can be seen to decrease with increasing afterload (total load), but increase with preload. | Shortening velocity and total shortening, Relation to total load and inotropy. Both can be seen to increase with inotropy, but decrease with load. |

As we see, both increased preload and inotropy wil increase the muscles ability to develop tension, and thus the shortening and shortening velocity in an isotonic experiment. This can also be shown alternatively:

|

|

Stretching the muscle before stimulation, increases tension. The increase in passive tension will be present at rest, before twitch, and is equal in baseline and inotropic state. During twitch, there is an increase in total tension with increasing pre twitch length. The increase in contractile tension is then the difference between the passive and the total curve. At a certain length, active tension starts to decline, even if passive and total tension still increases. This effect is additional to the effect of inotropy. | Myocardial shortening vs pre-, afterload and contractility. shortening increases with preload, as shown in both panels, although to a certain extent, until the preload insensitive zone (where active tension starts to decline, but passive tension still increases). Shortening is the resultant of force vs. afterload, the higher the afterload, the less the shortening, for a given contractility. Contractility is the load independent part of force development. The higher the contractility, the more the shortening for a given afterload. |

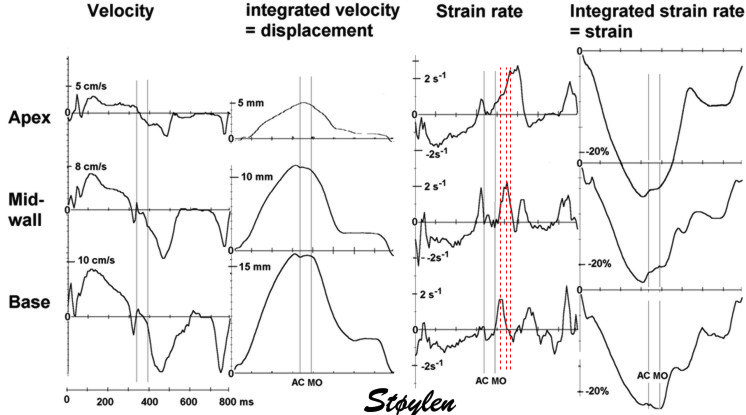

Thus, both shortening (strain) and peak rate of shortening (peak strain rate) is load dependent, and not independent measures of contractility, and looking at imaging, it is difficult to discern between reduced contractility and reduced load as shown below. This means, of course, that both strain and strain rate are load dependent.

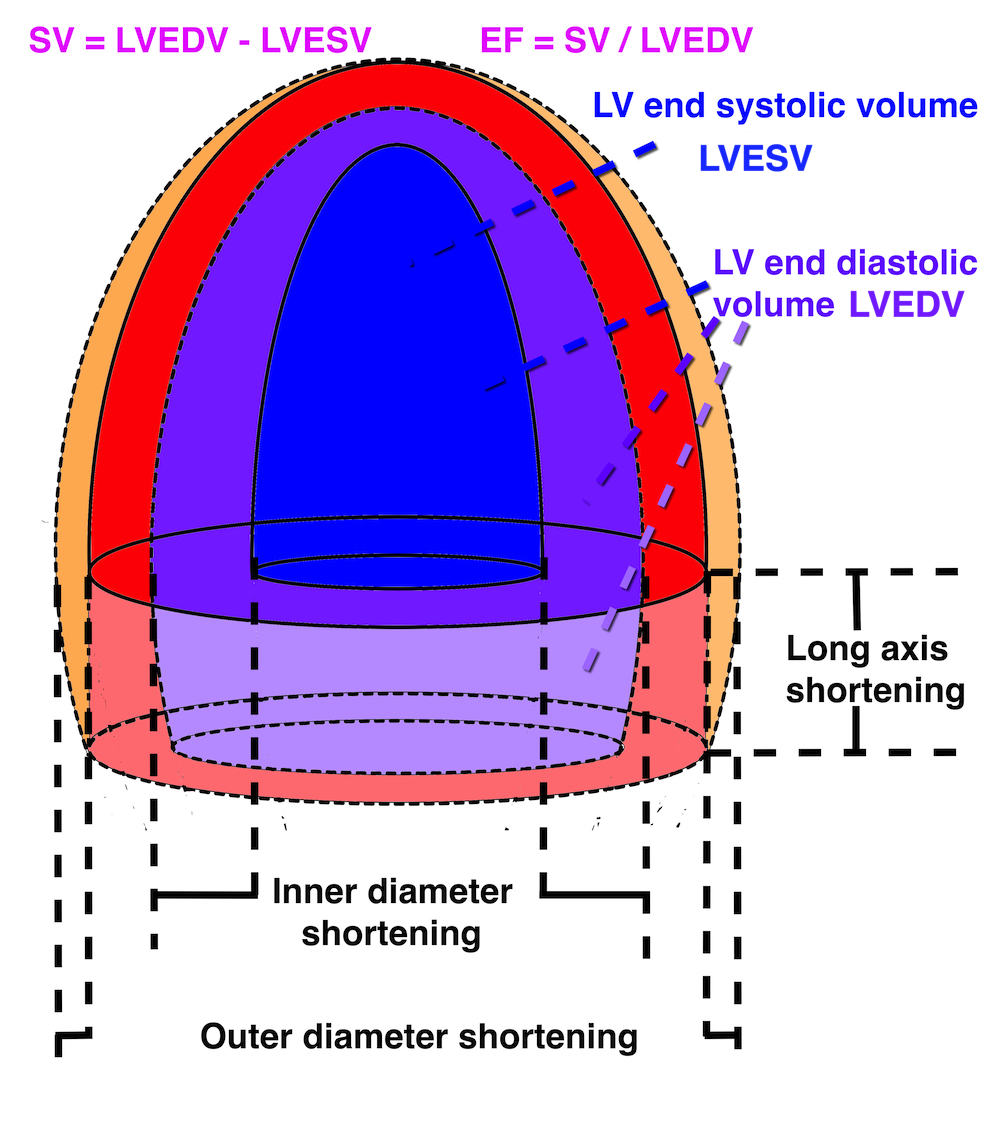

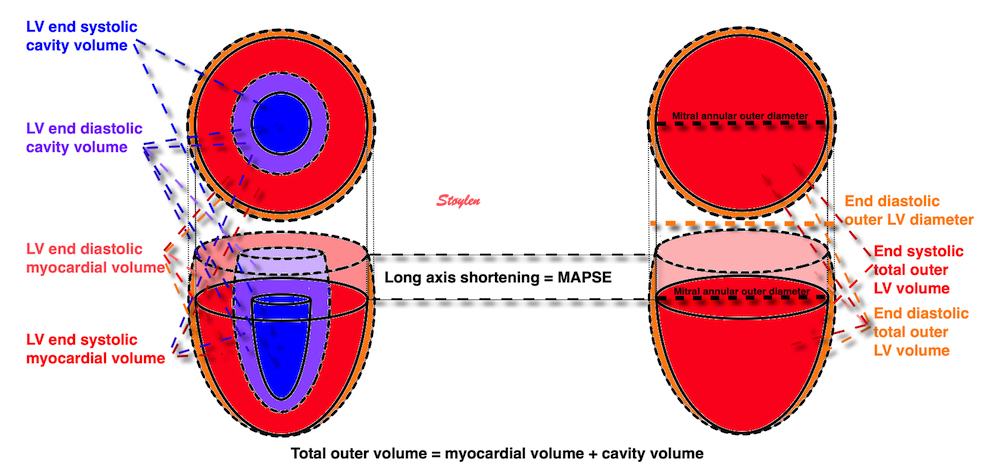

Cardiac volumes

|

|

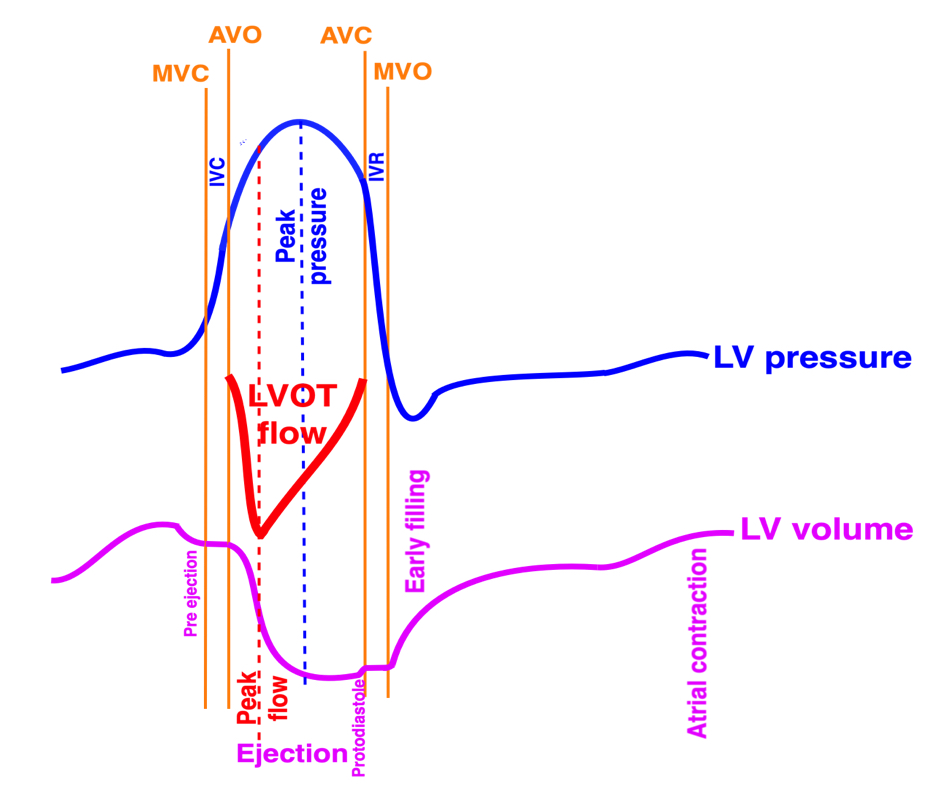

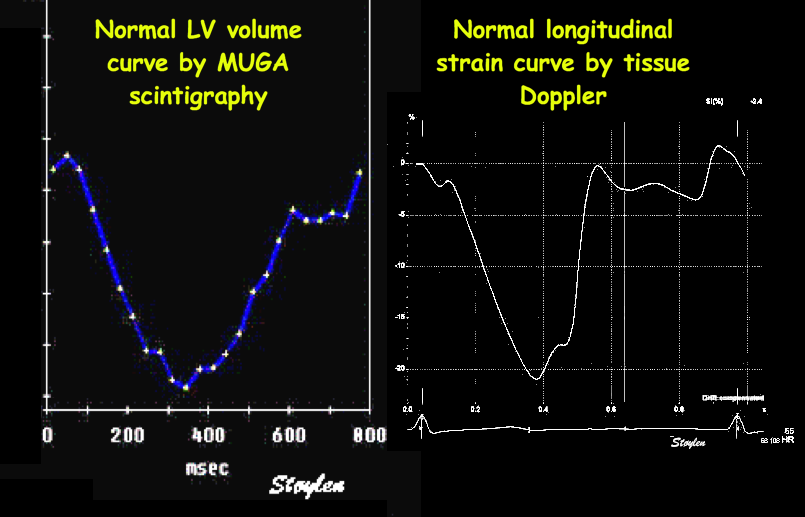

Isotonic isometric twitches tension diagrams above, length diagrams below. From the diagrams, it is evident that shortening only starts after tension equals load, and thenthe muscle shortens isotonically. Peak rate of shortening (peak strain rate) is at the start of shortening, and then declines (the slope of the shortening curve) . Only in the totally unloaded situation does the muscle start to shorten art start contraction. In the loaded situations, peak rate of force generation (RFD), occurs during the isometric phase, before peak rate of shortening. Peak shortening (peak strain), on the other hand, is at the end of the isotonic phase. | Comparing a tension length diagram of an isotonic/isometric twitch, and a pressure/volume (Wiggers)diagram. I've added the division of pre ejection into protosystole and IVC as discused above. The ejection period is not isotonic, as pressure increases and then decreases, and the myocardial tension must follow a similar course. Thus the tension increase is only during the first part of ejection, and then tension decline, so last part of ejection is relaxation. However, the volume curve will reflect the fibre lengthening and shortening, which makes is very obvious that strain and strain rate are about volume changes. Peak shortening is at en ejection, when volume is smallest. The conventional Wiggers diagram as shown by Brutsaert (black) describe the steepest volume decrease at the time of AVO, but as flow takes some time to accelerate, the peak volume decrease rate (which equals peak flow rate, must be slightly delayed after AVO). This is shown by the red part of volume curve. |

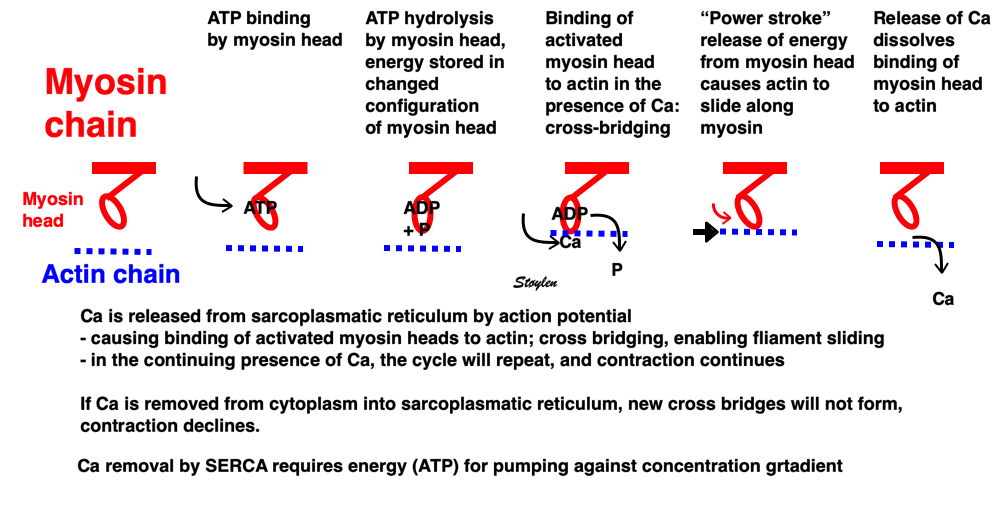

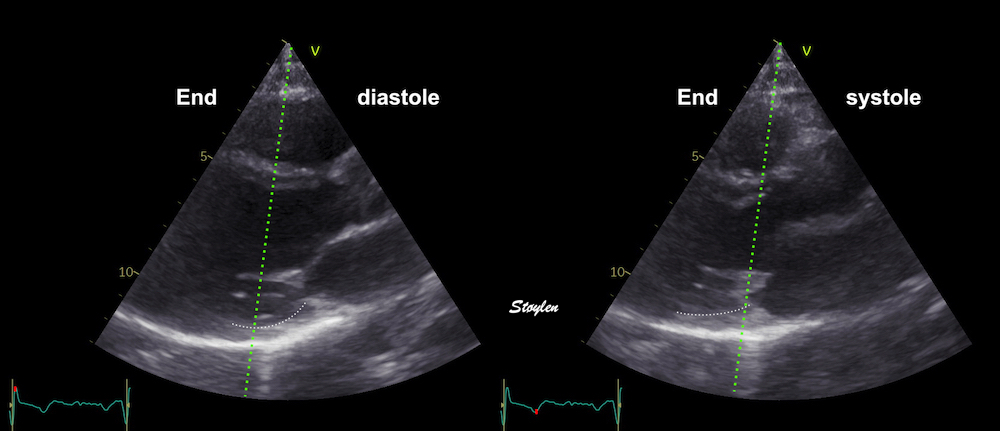

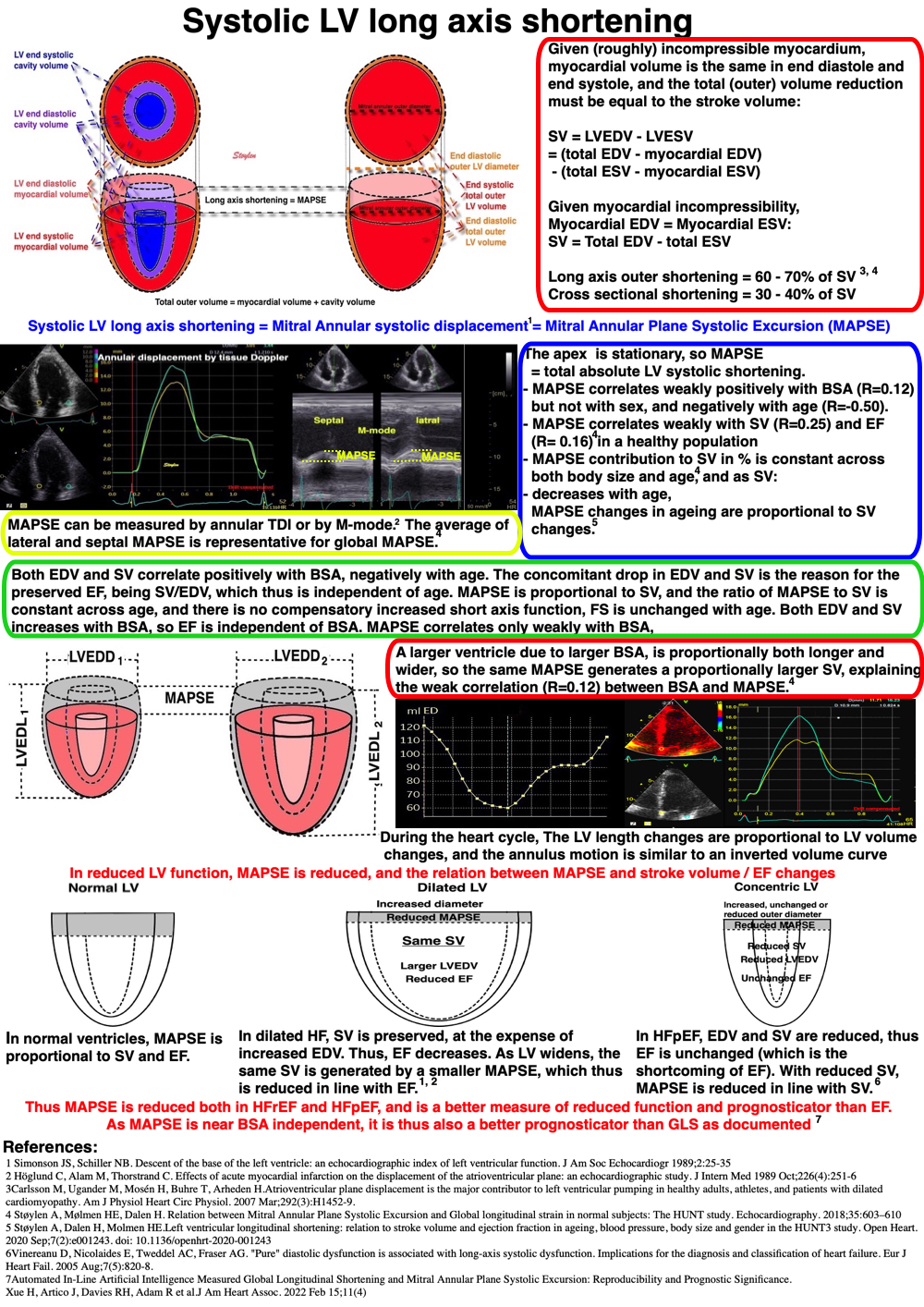

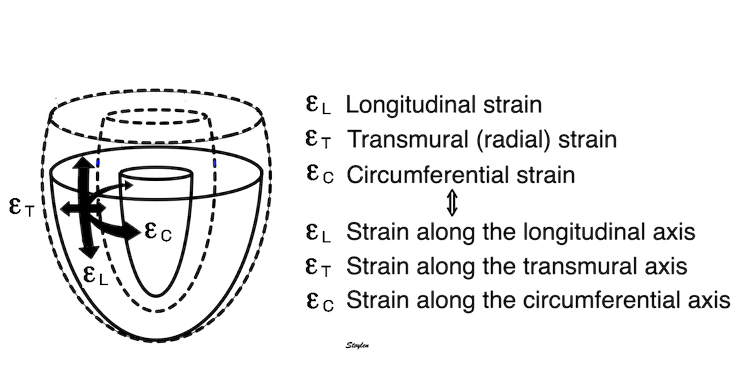

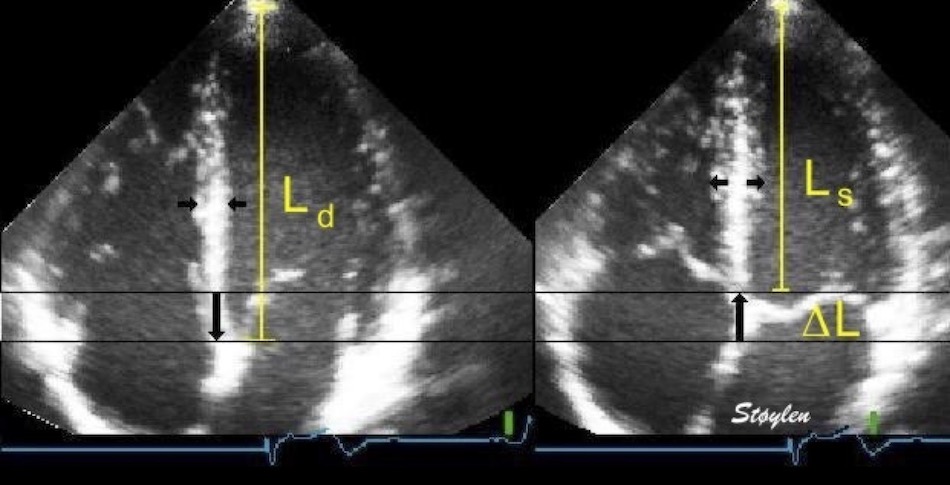

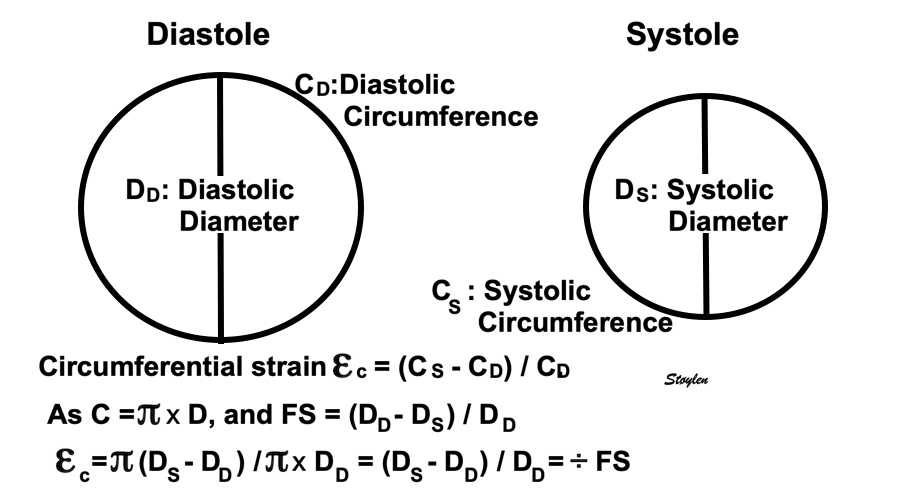

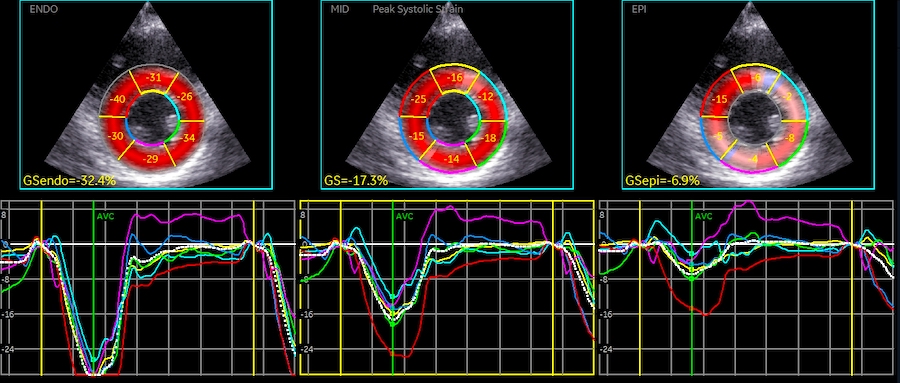

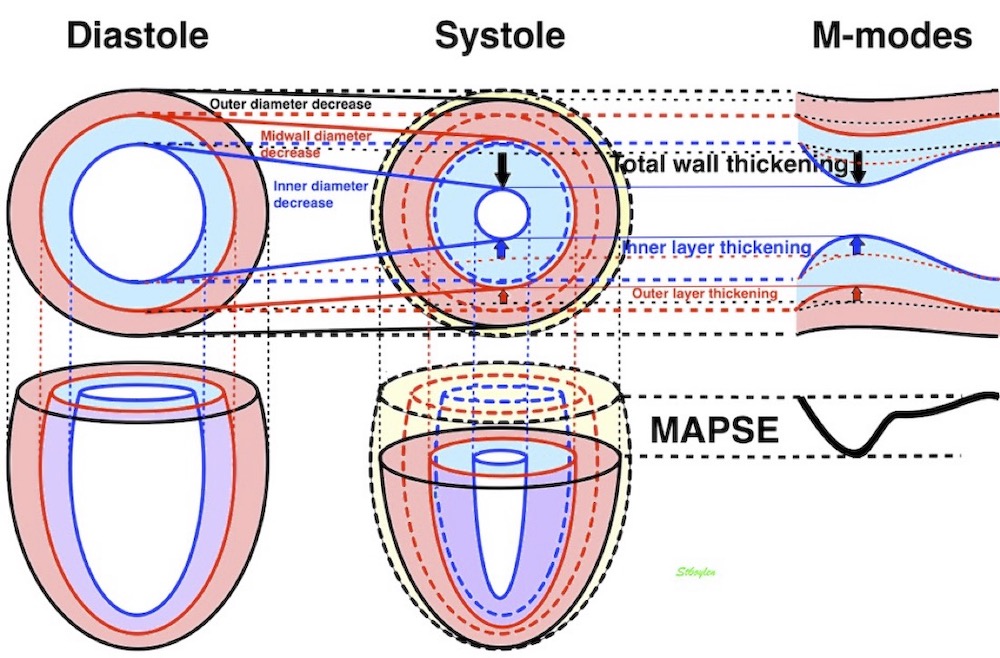

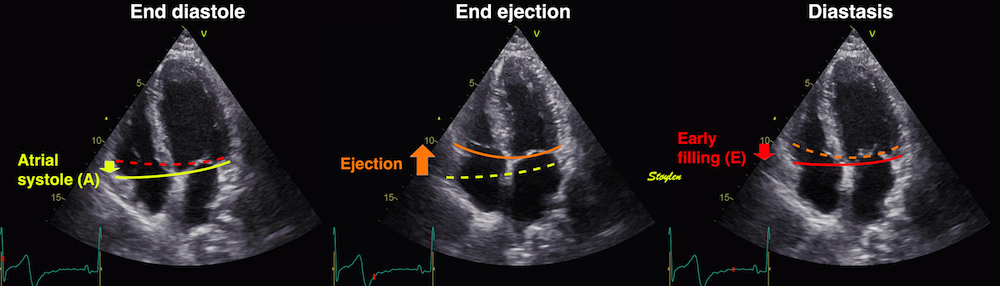

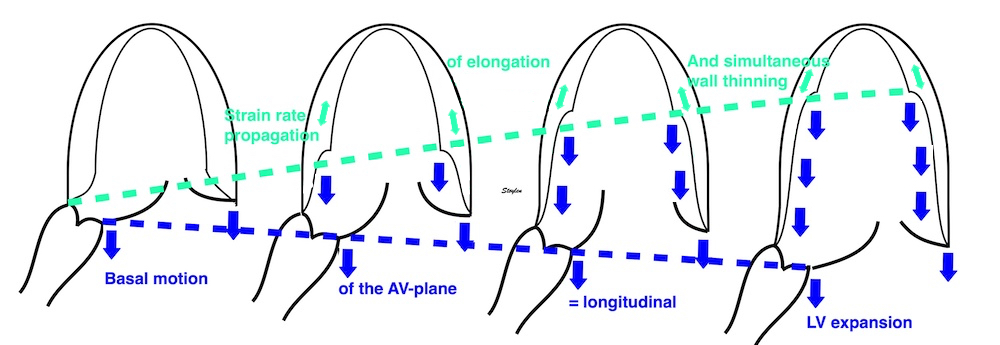

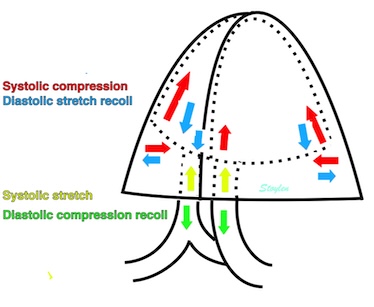

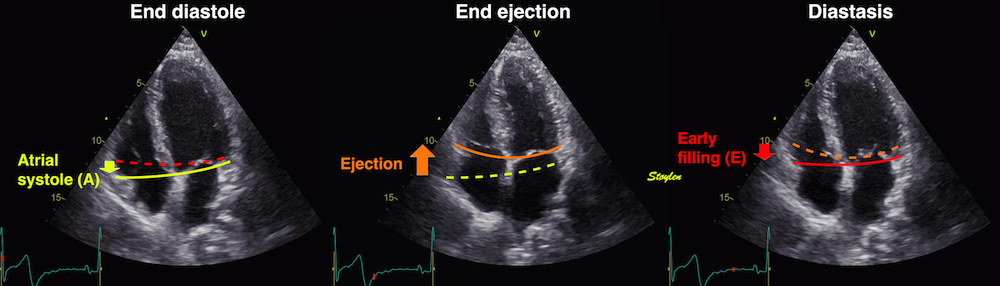

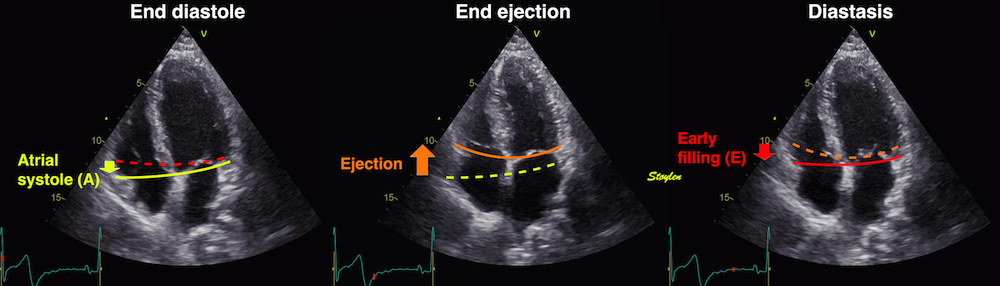

Volume changes and muscle fibre length changes are analogous, of course, as systolic decrease in volume has to be accompanied by muscle shortening, diastolic increase in volume by muscle lengthening. As described in the basic concepts page, there is systolic circumferential and longitudinal shortening, and fibre shortening, while transmural strain is not fibre shortening, but thickening.

Deformation of the myocardium. In systole, there is volume reduction, as well as longitudinal and circumferential shortening. The strains are related to volume change, as shown above.

However, the strains are coordinates of the myocardial deformation, not direct measures of fibre shortening. While circumferential shortening is geometry related, longitudinal shortening is the one that is most closely related to volume change, and thus to fibre shortening.

|

|

|

Shortening curves related to afterload, modified from the figure above. The shortening in percent, is equivalent to the longitudinal strain of the muscle. | Strain curve from a normal subject. The strain curve is fairly similar to the shortening curves to the left. | The picture shows a detailed LV volume curve from a healthy person by MUGA scintigraphy, showing how analoguous the strain curve is to the volume curve. |

So now, we can relate the physiological findings in isolated muscle to the volume changes originally descrtibed in Frank Starlings law:

|

|

Acute increases in end diastolic filling, will increase the stroke volume along the curve shown. This effect was observed with both increased venous pressure, but also with decreased stroke volume in previous beat, resulting in an increased EDV. Within physiological limits there is an increase, but with increasing dilatation, there will be less response. However, at least in normal hearts, there is little evidence for a descending limb of the curves. It is important that Frank Starlings law is about acute volume changes, not chronic changes as in hypertrophy or dilation. The curve shows the preload (which is | SV versus afterload. Shortening is the resultant of force vs. afterload, the higher the afterload, the less the SV, for all preloads. |

Thus, global strain rate and strain are not load independent, as explained above. One would almost say of course. Force is the primary effect of contraction. Deformation is secondary to force, and depends on load. Motion is the summation of deformation. The systolic volume change of the ventricle is related to the resistance, which again is a function of both pressure and vascular resistance. What we measure with deformation parameters, is only the changes in volume, and thus the wall deformations.

thus, physiologically the rate and amount of longitudinal shortening should decrease with increasing load. Anything else would be counter intuitive.

The heart cycle can basically be described in terms of volume changes, which in turn are the function of ejection and filling:

This is slightly simplified, as will be explained later.

The true isovolumic contraction time (IVC) is defined from MVC to the start of ejection. Thus, in this phase there is no volume change, and, hence, no deformation.

This phase it on the other hand, the period of most rapid pressure rise, peak dP/dt, which occurs during IVC, close to the AVC (105). This represents the most rapid rate of force development (RFD). As this phase is basically not influenced by aortic pressure, it is largely afterload independent, except for the Laplac e effect: It's important to realise that the Frank-Starling balance and the pressure volume loop both relate to acute changes in ventricular volume. The physiologic differences in EDV between individuals, and in chronic LV enlargement, are not responsible for preload. On the other hand, by the law of Laplace:

![]()

LVEDV is part of the afterload, the tension must be proportional to the radius: As the intraventricular pressure acts on a larger surface, and thus the force that has to be generated must be proportional to the surface area for the same pressure. dP/dt increases with inotropy (106, 107)

On the other hand, dP/dt is preload dependent as any contraction measure (106, 107).

|

|

Muscle twitches, showing that the most rapid rise of tension occurs during isometric contraction, but the highest rate of shortening occurs in the bunloaded muscle before peak RFD. | Peak rate of pressure rise, which is the closes correlate to the rate of force/tension development. This occurs during IVC |

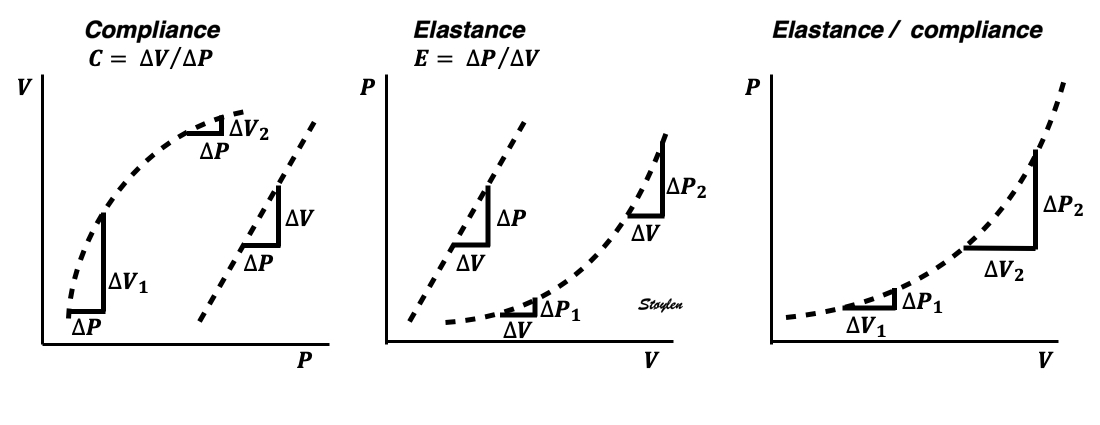

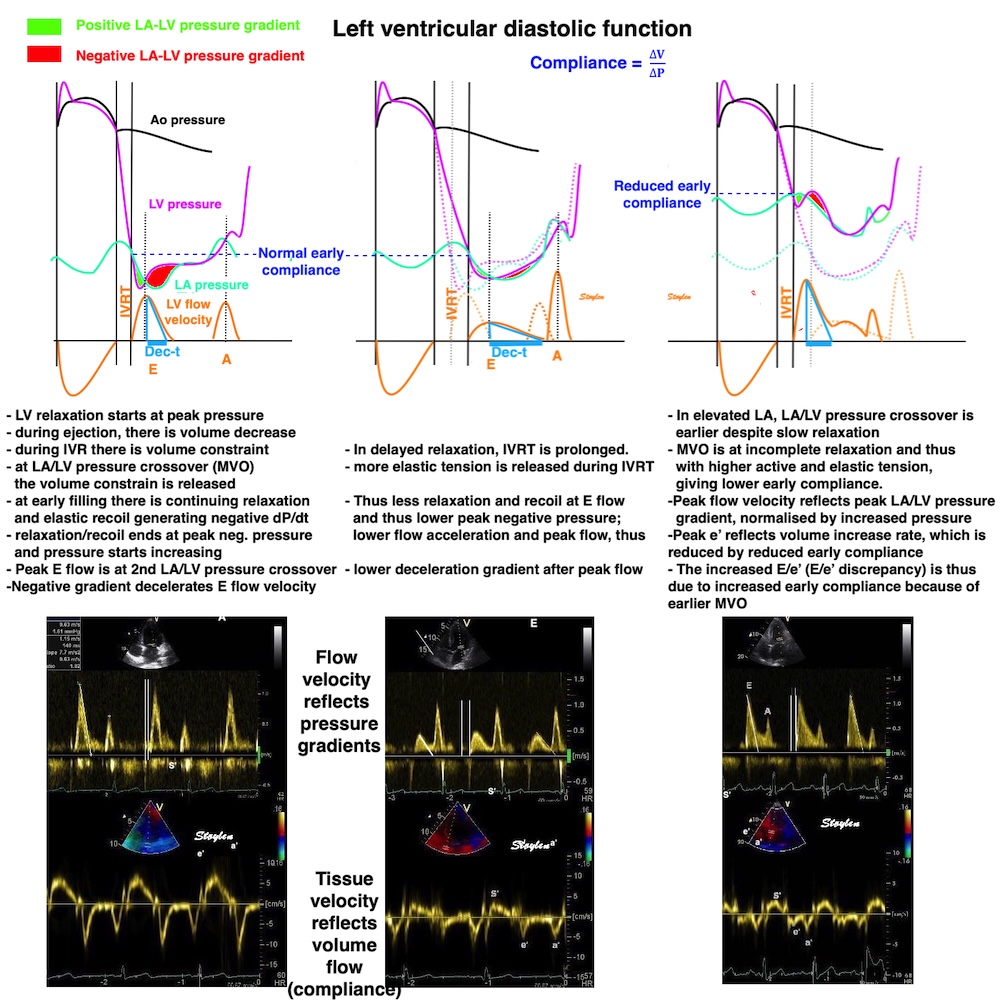

Compliance (distensibility) is defined as C = ![]() V /

V / ![]() P, i.e. how much does the volume increase for a given increment in pressure. Elastance is the inverse value E =

P, i.e. how much does the volume increase for a given increment in pressure. Elastance is the inverse value E = ![]() P /

P / ![]() V, i.e. how much does the pressure increase for a given increment in volume.

V, i.e. how much does the pressure increase for a given increment in volume.

Compliance describes the volume a a function of pressure, and hence, should ideally be described in a volume-pressure diagram. The figure shows linear compliance, as well as decreasing compliance (decreasing volume per pressure increment), as can be seen in an elastic system. | Elastance, despite simply being the inverse of compliance, describes pressure as a function of the volume, and thus is best describel in a pressure-volume diagram. Here is shown linear elastance, as well asincreasing pressure for the same volume increments, as can be seen in an elastic system. | The pressure volume volum loops is generally described in a pressure volume diagram, i.e. showing volume as ordinate and pressure as abscissa. However, both compliance and elastance can be shown in this diagram, obviously, as both describe the ratios between pressure and volume increments. |

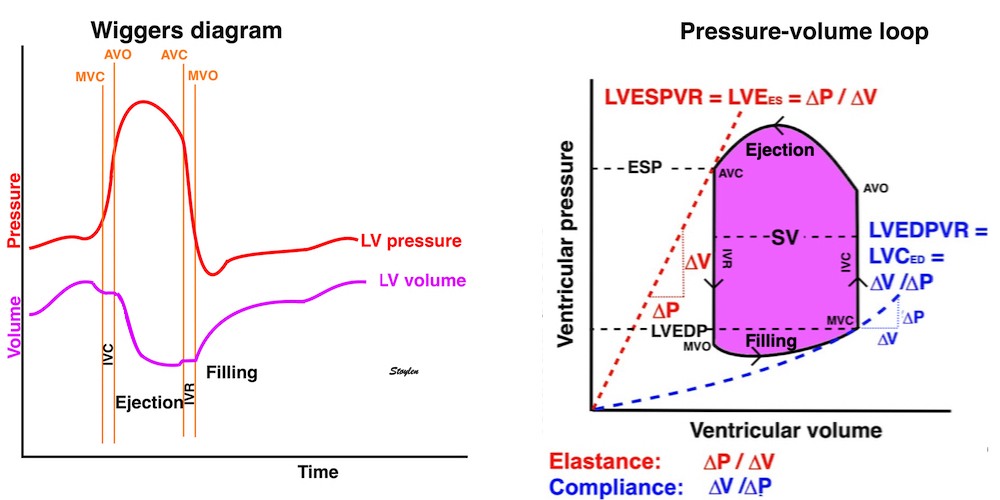

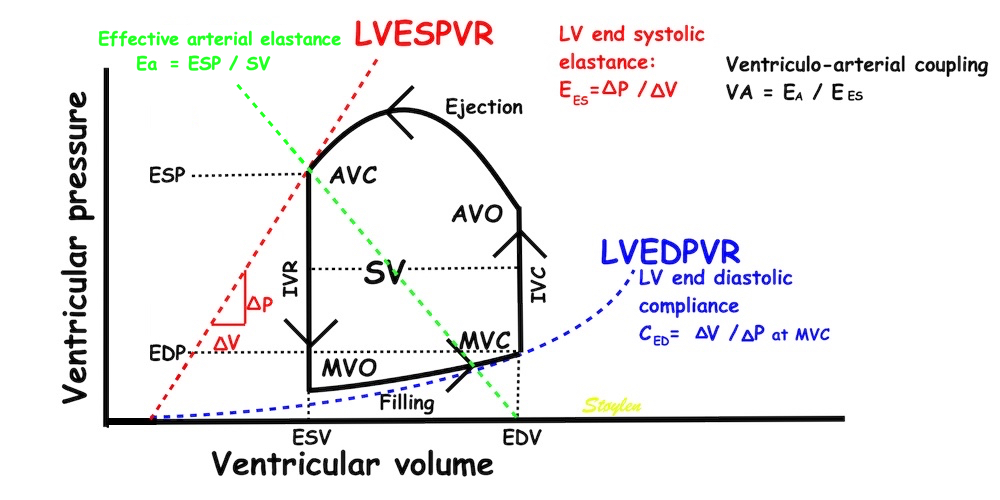

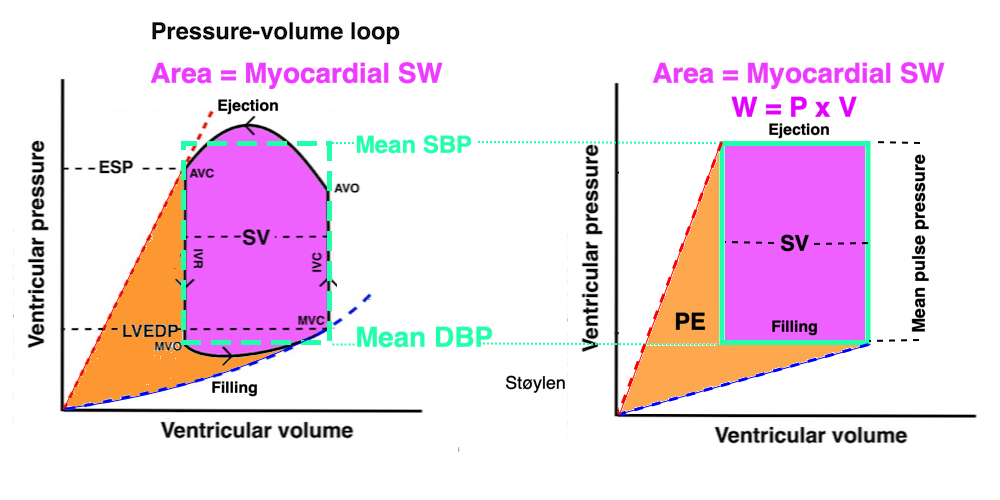

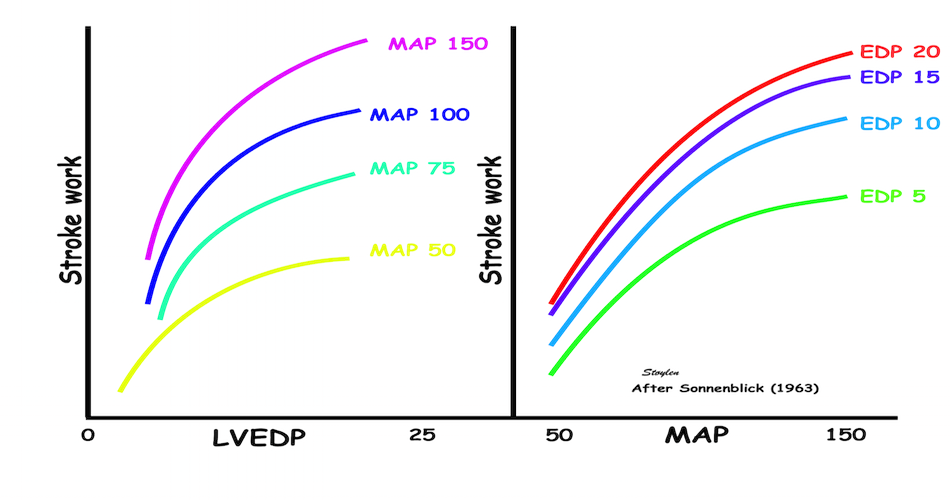

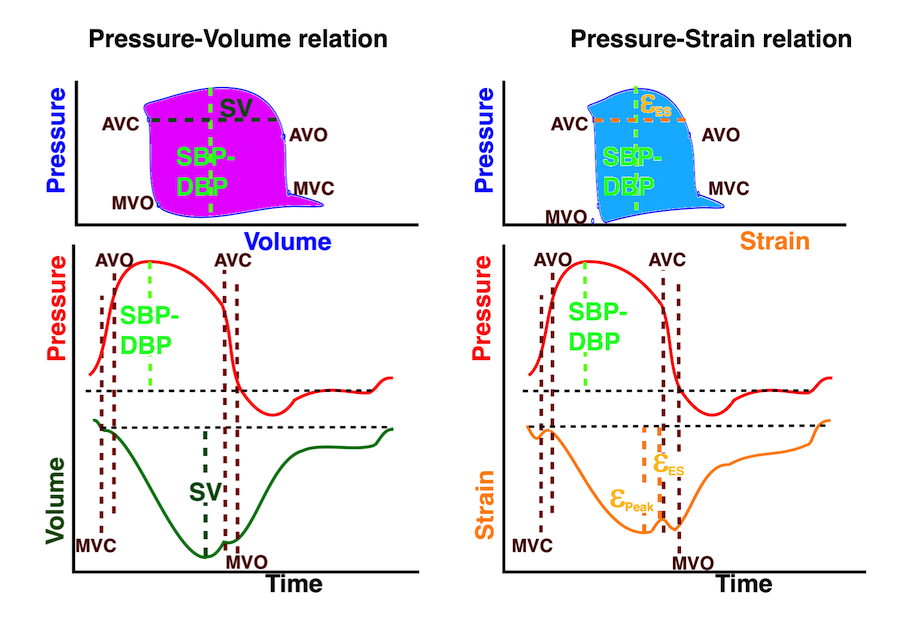

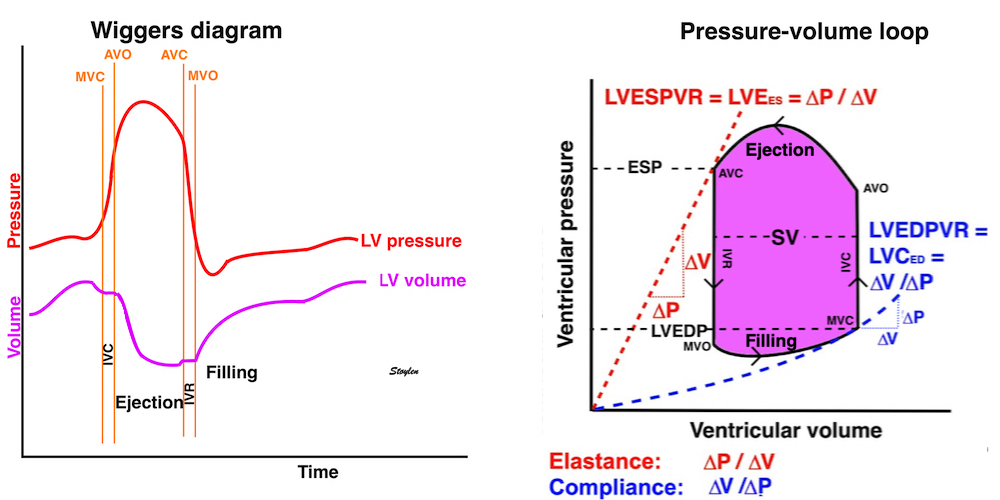

The length - tension relation in isolated muscle is equivalent to the pressure - volume relation in the intact heart. To go into the concept of cardiac work and contractility, the whole heart cycle has to be considered. Basically, pressure-volume loops are useful concepts for visualising and explaining the relations between stroke volume, pressure, contractility and LV work.

The pressure-volume loop on the right is derived from the pressure and volume curves on the left. It is basically a tool to assess and explain the relations between contractility, load and output. Isovolumic contraction (IVC) is between MVC and AVO, there being no volume change, this is a true isometric contraction. Isovolumic relaxation is between AVC and MVO, this is the isometric phase of relaxation. Pressure volume diagram of a heart where pressure is plotted against volume, a pressure-Volume loop (PV-loop). Pressure-volume loops are useful concepts for visualising and explaining the relations between stroke volume, pressure, contractility and LV work.The version shows the cardiac phases, with the same simplifications as the Wigger's diagram to the left; rapid filling is shown as a passive event, and as valve openings and closures are shown at pressure crossover. Time runs around the loop in a counterclockwise direction. The width of the loop is equal to the stroke volume. The top of the diagram shows the pressure curve during ejection, and the height of the loop is the systolic - diastolic pressure difference. The tangent to the end systolic pressure-volume, is the ventricular elastance ![]() P /

P / ![]() V.

V.

In filling of any hollow organ, the elastance is usually taken to mean how much pressure increase a given volume increment generates as described above, and the definition of elastance is ![]() P /

P / ![]() V.

V.

End systolic LV elastance is defined as the slope of the straight line trough the end systolic pressure volume corner of the pressure volume loop. It has been shown to be nearly linear trough multiple pressure volume loops obtained by manipulating the pre and afterload. However, the straight line has not been shown to be crossing the zero point, i.e. the volume is not necessary zero when pressure is zero.

End systolic elastance is a function of LV emptying. Thus this must be taken to mean how much pressure the LV must generate for a given volume ejection (SV), but the definition is ![]() P /

P / ![]() V, and thus conforms with the definition of elastance.

V, and thus conforms with the definition of elastance.

The PV loop shows the relation between load, SV and contractility in acute changes.

|

|

|

Effect of preload. Increased preload (increased LVEDV - the right side of the curve moves right, the loop becomes wider), will, through the Frank-Starling balance increase stroke volume. This increased stroke volume will be ejected at the same pressure, thus returning to the same point on the ESPVR line. | Effect of afterload. Increased afterload (increased SBP moving the top of the curve upwards), will reduce the stroke volume. The end systolic point moves up the ESPVR line, shortening the width of the loop, i.e reduced SV. | Effect of inotropy. Inotropy shifts the ESPVR line to the left, thus increasing the force and LV emptying, increasing stroke volume through reduced LVESV, but also increasing the pressure, both through increased contractile force and increased volume being ejected into the vascular bed. |

|

|

|

In reality, an increased SV will cause increase in SBP, causing an increased afterload on the same beat, thus reducing the effect on SV somewhat, through interaction between pre- and afterload. | In reality, an acute increase in afterload, will reduce emptying (increased LVEDV), so on the next beat, the preload is increased, partly offsetting the effect of afterload on SV. | In reality, decreased LVESV, without increased venous return, will in the next beat result in reduced LVEDV, thus offsetting the effect of inotropy somewhat by reduced preload. |

Ventricular elastance, is thus a load independent measure of contractile force (84).

In reality, this index is not easily obtainable in the clinic, even in continuous invasive monitoring, as volume measurements are not available in routine monitoring. But in animal experiments, using conductance catheters, where multiple pre- and afterload manipulations can be done, and where the ESPVR can be obtained by linear regression, it serves as a reference method, to test other contractility indices.

However, the LV elastance may not be a perfect gold standard anyway.

- Firstly, using end ejection for end systole, means that measurements are done at a point in time where the myocardium is in relaxation (but not relaxed) phase as discussed below.

Several studies have found that the ESPVR is not a straight line, curvilinear depending on contractility (85, 86), and afterload (87, 88).

Peak systolic pressure volume relation might be closer to the real thing, but is not easily discernible.

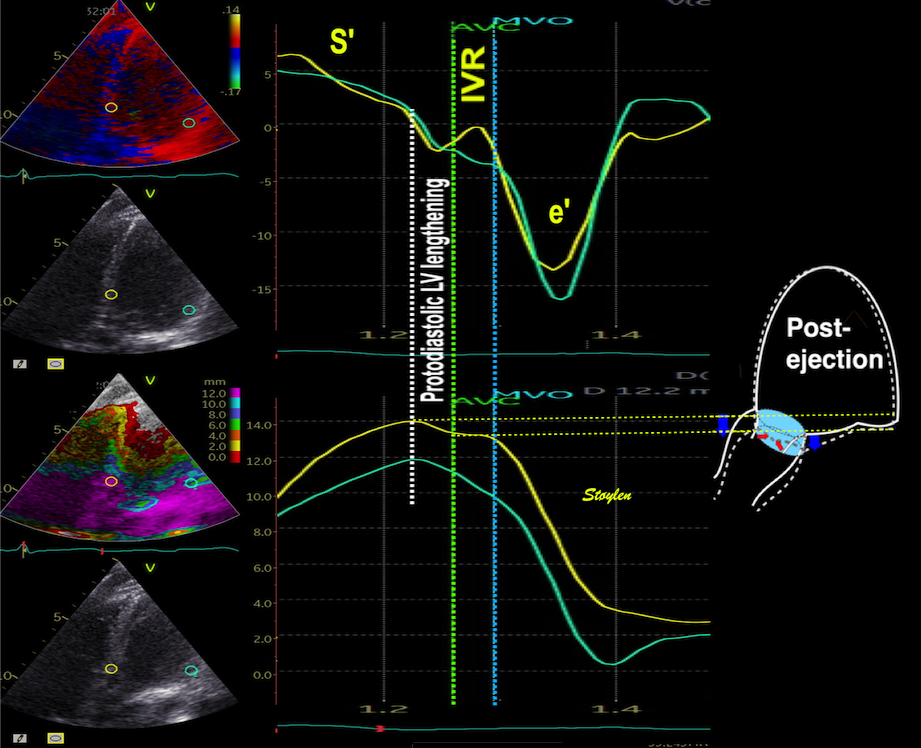

- Secondly, as we'll see later, the true end systolic volume is not easily defined due to the protodiastolic volume decrease as discussed below.

Finally, however, of course these volume considerations are only related to acute changes. In inter individual differences in healthy individuals, as well as in LV dilation, the EDV is not a measure of preload, and the PV-loops can only be interpreted in relation to the individual. PCWP, on the other hand, is a measure of preload, that is relatively standardised and thus a more universal measure of preload when applied across individuals, although it does not take the Laplace effect into consideration, the LV volume will stioll contribute to after- (or total load).

Volume: It's important to realise that the Frank-Starling balance and the pressure volume loop both relate to acute changes in ventricular volume. The physiologic differences in EDV between individuals, and in chronic LV enlargement, are not responsible for preload. On the other hand, by the law of Laplace:

![]()

LVEDV is part of the afterload, the tension must be proportional to the radius: As the intraventricular pressure acts on a larger surface, and thus the force that has to be generated must be proportional to the surface area for the same pressure.

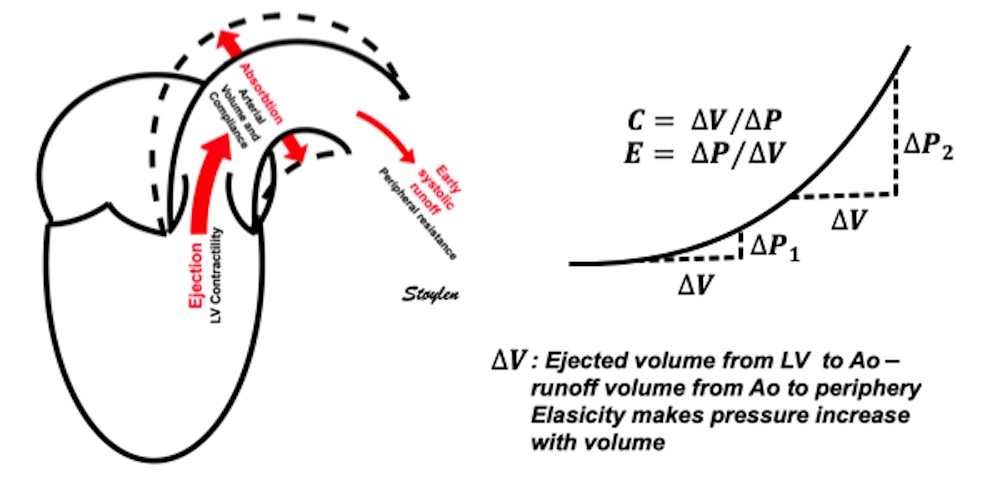

Pressure: The pressure, is the systolic pressure, which varies during the ejection:

| |

The ejection period is not isotonic, as pressure increases and then decreases, and the myocardial tension must follow a similar course. Thus the tension increase is only during the first part of ejection, and then tension decline so last part of ejection is relaxation. The volume curve (as given by Brutsaert - black) is erroneous. Due to the acceleration of blood, the peak flow rate, and thus the rate of volume decrease must be somewhat later than the AVO, as shown by the red curve. | With conventional pressure/flow recordings, the peak pressure / tension is around mid ejection, but looking at flow, peak flow through aortic ostium is much earlier during ejection. As flow rate equals the rate of volume decrease, peak flow must indicate peak rate of volume decrease. |

2. The tension increase is closely related to distension of the large vessels. The elasticity (compliance) of the arterial (especially the aortic) wall. During ejection, the volume ejected into the aorta and distends it. The more distensible the aortic wall (the higher the compliance ![]() V /

V / ![]() P - the volume increase per pressure unit), the less the pressure in the aorta will rise, and the lower the CAP. The stiffer the aorta, the less it will be distended (the less the compliance) for a given pressure increase, or conversely the more the pressure has to be increased in order to inject a certain volume (stroke volume) into the aorta. Thus, increased arterial stiffness will increase the systolic pressure, and hence, the afterload (108).

P - the volume increase per pressure unit), the less the pressure in the aorta will rise, and the lower the CAP. The stiffer the aorta, the less it will be distended (the less the compliance) for a given pressure increase, or conversely the more the pressure has to be increased in order to inject a certain volume (stroke volume) into the aorta. Thus, increased arterial stiffness will increase the systolic pressure, and hence, the afterload (108).

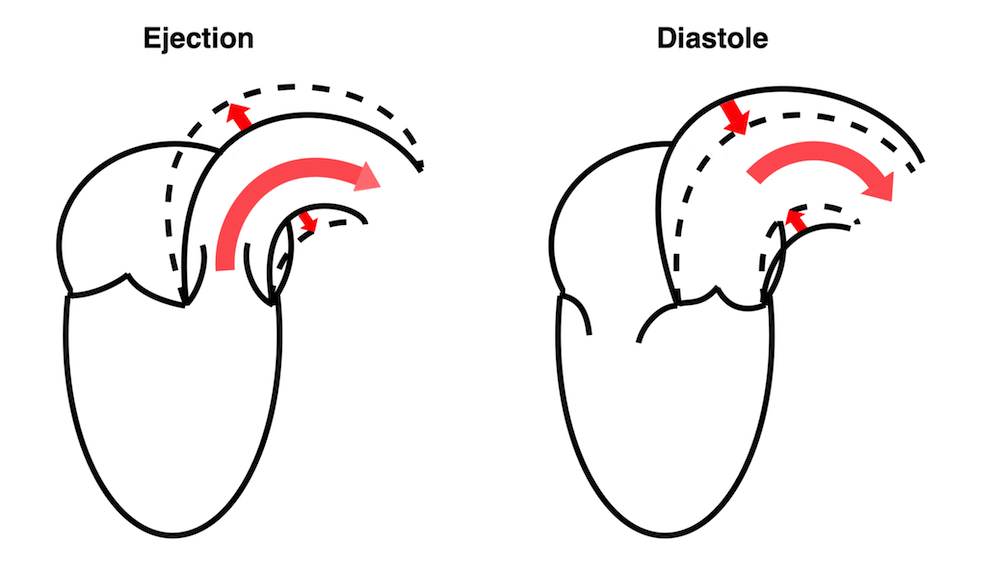

During ejection, the volume is ejected into the aorta, which is distended, storing energy in the elastic properties, and then contracting again during diastole, acting as a diastolic pump, with energy stored from systole.

The ventricle ejects the full stroke volume into the arterial bed during systole. However, there is systolic run off to the periphery, so the volume distending the arterial bed is less then the stroke volume. Thus the ![]() V distending the artery is less than the total SV, and the difference is determined by the peripheral resistance, and the pressure drops toward end systole.

V distending the artery is less than the total SV, and the difference is determined by the peripheral resistance, and the pressure drops toward end systole.

Ventricular ejection distends the arterial bed, and the elastic properties results in pressure increase related to the volume, and the compliance decreases as the volume increases. However, the run-off into the arterial bed, during systole, leads to the end systolic volume (and pressure) is less than the total SV. This run off is determined by the peripheral resistance.

The pressure is inversely related to the arterial compliance, or directly related to the elastance ![]() P /

P / ![]() V (the pressure increase per volume unit), and is the inverse of arterial compliance. As the pre arteriolar arteriaø bed is elastic, there is thus no reason to believe that the arterial elastance is linear. Arterial eleastance could also be both end diastolic, peak systolic or end systolic.

V (the pressure increase per volume unit), and is the inverse of arterial compliance. As the pre arteriolar arteriaø bed is elastic, there is thus no reason to believe that the arterial elastance is linear. Arterial eleastance could also be both end diastolic, peak systolic or end systolic.

Thus, what is called "effectve arterial elastance" is defined as SV / ESP. But this, of course defines a straight line slope, even if this is improbable, so this concept is only valid for end systolic pressure and SV. However, using ESP takes into account the whole of the SV, but also the fall i pressure from peak to end systole, which is a function of the run off during systole, and thus peripheral resistance. Thus, it is a measure of afterload taking both components of the arterial bed into account (260 - 262).

PV-loop illustrating effective arterial elastance. The arterial elastance is a measure of how much pressure the stroke volume generates in the arterial bed,

and is simply EA = ESP/SV, which is the slope of the line crossing zero at the end diastolic volume, and the point defined by the end systolic volume and pressure. It is the arterial pressure increase in relation to the stroke volume. The ventricular elastance is LV end systolic elastance, the pressure generated by the ventricle fpr ejecting the stroke volume; EES = ESP/ESV. But then, given that the theoretical volume of the LV for pressure P =0 is V = 0, then EA / EES = (ESP/SV)/(ESP/ESV) = ESV/SV = (EDV - SV)/SV = EDV/SV - 1 = 1/EF - 1. Thi9s of course is not necessarily the case, but depends on the placement and slop of the LVESPR line. Thus the concept of VA coupling simply eliminates the pressure, and ends up with a load dependent measure of LV performance as a result of this load!

Pulse wave reflection at the level of the aortic root. In the upper panel, pulse wave propagation velocity is lower, and the reflected wave from the previous heartbeat arrives after AVC, and will then augment the diastolic pressure only, not contributing to afterload. In the lower panel, due to a higher PWP, the reflected wave arrives before the AVC, and will augment the systolic pressure, which willl be higher than the peripheral pressure. Systolic pressure augmentation will thus add to the afterload.

Finally, of course, the body regulates both the cardiac performance and load in relation to the needs of the body:

Thus, of course, all factors of cardiac performance in the intact body may change in relation to the body's needs. But this may be a very complex regulation of the contractile state (by variations in inotropy), preload (by variations in venous return - venoconstriction; giving load dependent increase in contraction) and afterload by varying arterial tone (which again is often balanced by inotropy). The final variable is the cardiac output.

This means that heart rate is in itself a determinant for especially shortening rate, and more indirectly, shortening, and secondly to stroke work and cardiac output.

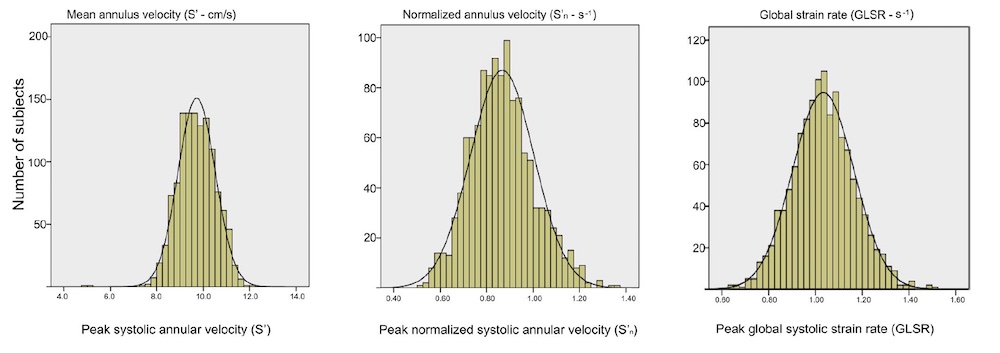

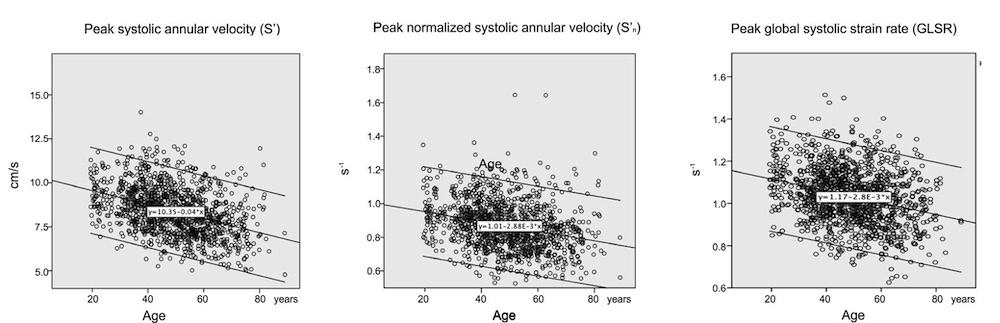

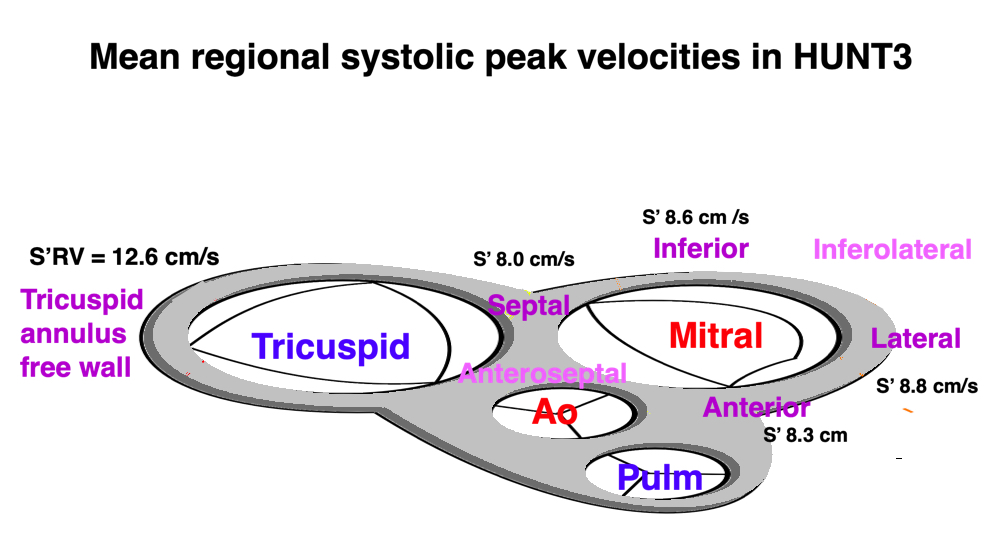

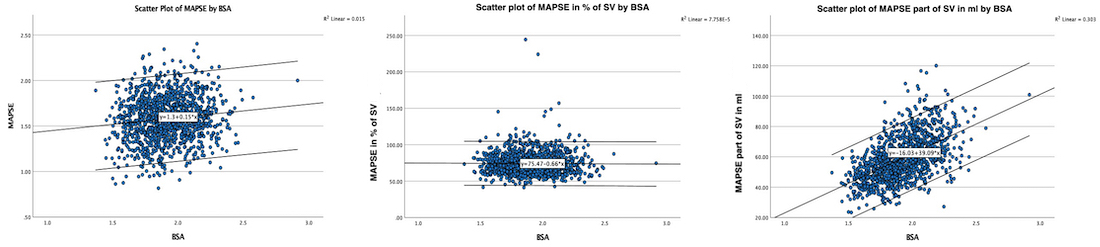

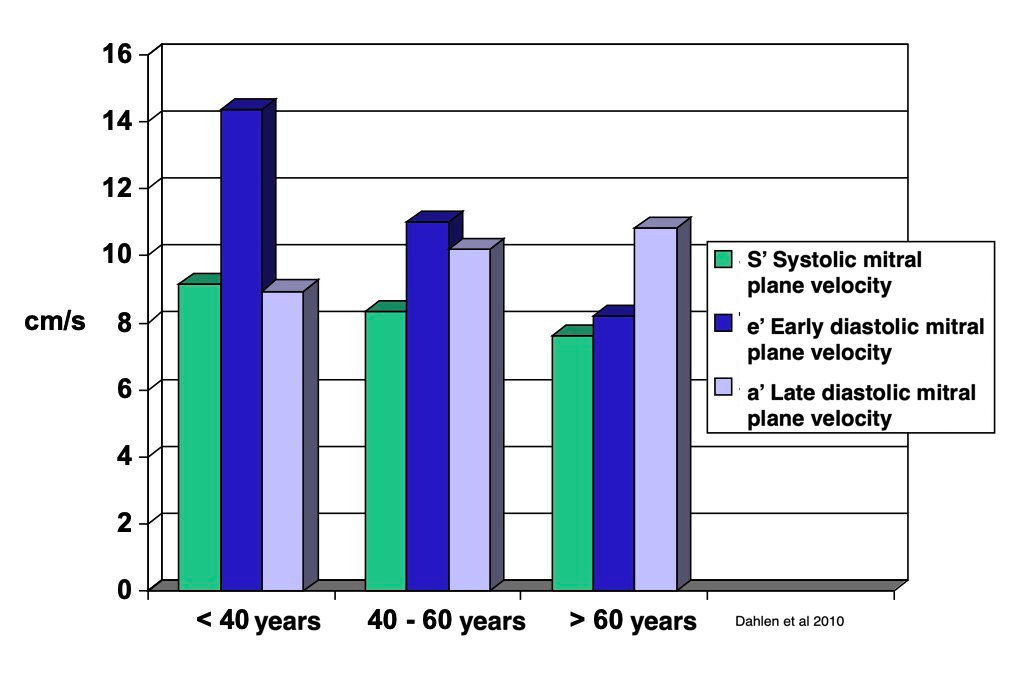

The HUNT3 (16) and 4 (249) are two of the largest normal single center studies of Echocardiography in the world. Both are similar in size (HUNT3 1266 vs HUNT4 1412), and with normal age distribution.

HUNT 3 | HUNT 4 | |||

Women | Men | Women | Men | |

Number | 673 | 623 | 788 | 624 |

Age (years) | 47.8 (13.6) | 50.6 (13.7) | 57.2 (12.4) | 57.8 12.4) |

BMI (Kg/m2) | 25.8 (4.1) | 26.5 (3.4) | 25 (4) | 26 (3) |

BP (mmHg) | 127 / 71 (17/10) | 133 / 77 (14/10) | 127 / 72 (18/9) | 131 / 78 (17/10) |

There was a slight difference in mean age. As many of the measurements are age related, the age distribution is important in comparing populations.

HUNT 3 was acquired in 2006 - 2008, HUNT 4 in 2017 - 2019. Thus the echo populations are two different cohorts, although there was some overlap, as participants from HUNT3 were invited to participate in HUNT4, but the individuals paticipating in both were aged 20 years, and the comparison will give further data an ageing.

Both normal studies excluded patients with heart disease, diabetes and hypertension.

HUNT3 was taken on GE Vivid 7, and analysed in EchoPAC version BT06, (except strain and strain rate, which was analysed in the proprietary segmental strain analysis software.

HUNT4 was acquired on GE Vivid E95 and analysed on EchoPAC version 203. Thus there were technical developmental differences as well.

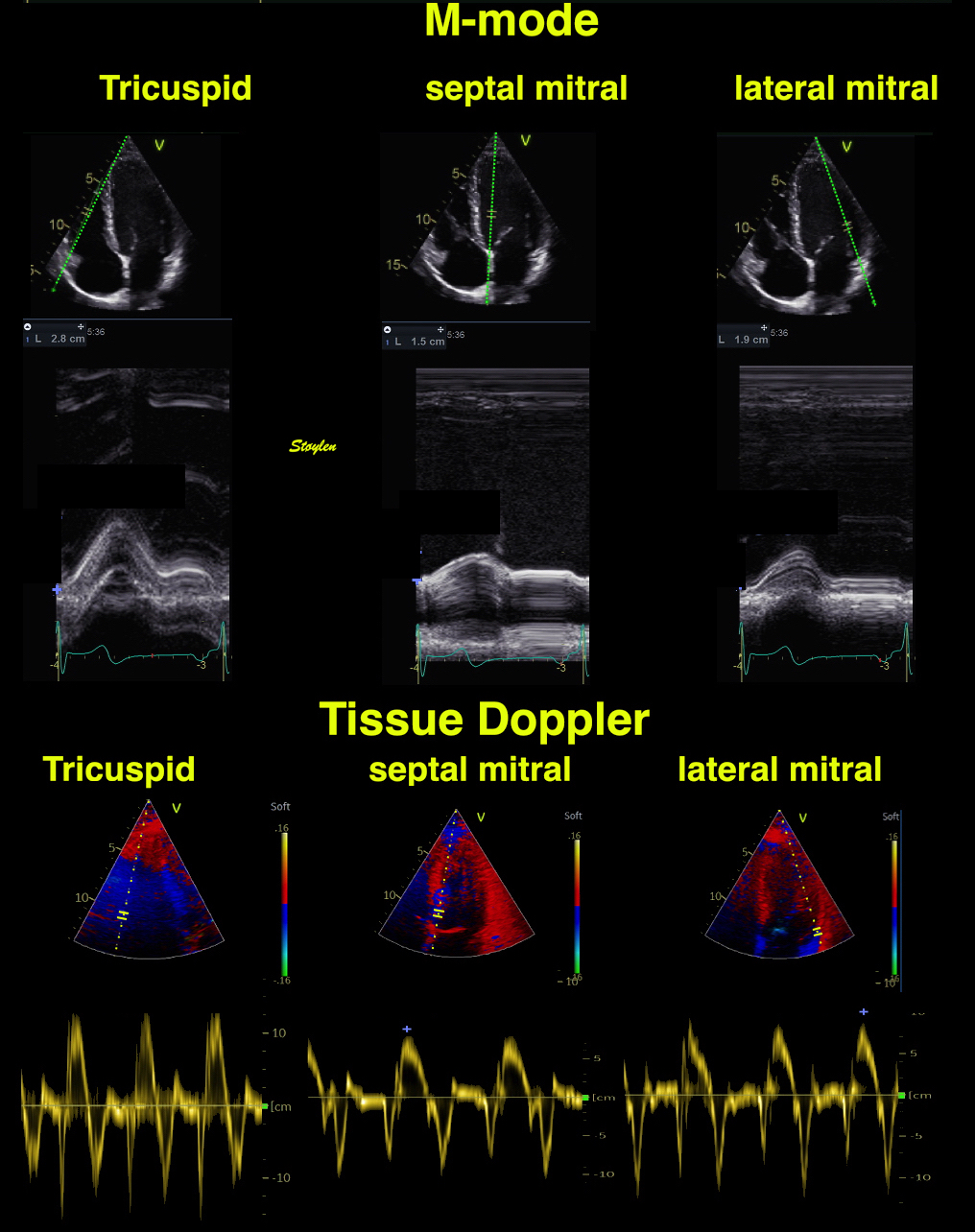

The two studies differ in much of the measurement methodology, meaning that comparison is interesting from a methodological viewpoint, but also in looking at age and sex relations across methods. In linear dimension measurements, HUNT 3 used mainly M-mode, HUNT4 B-mode.

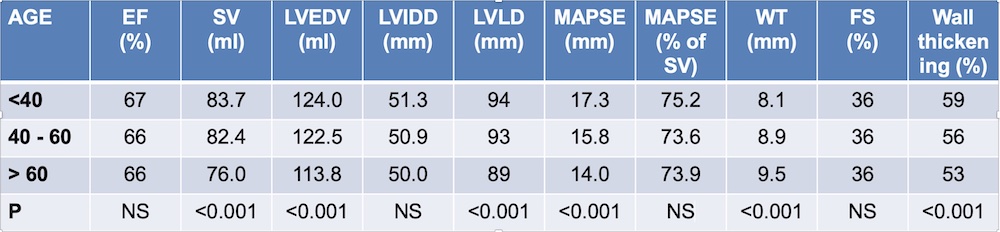

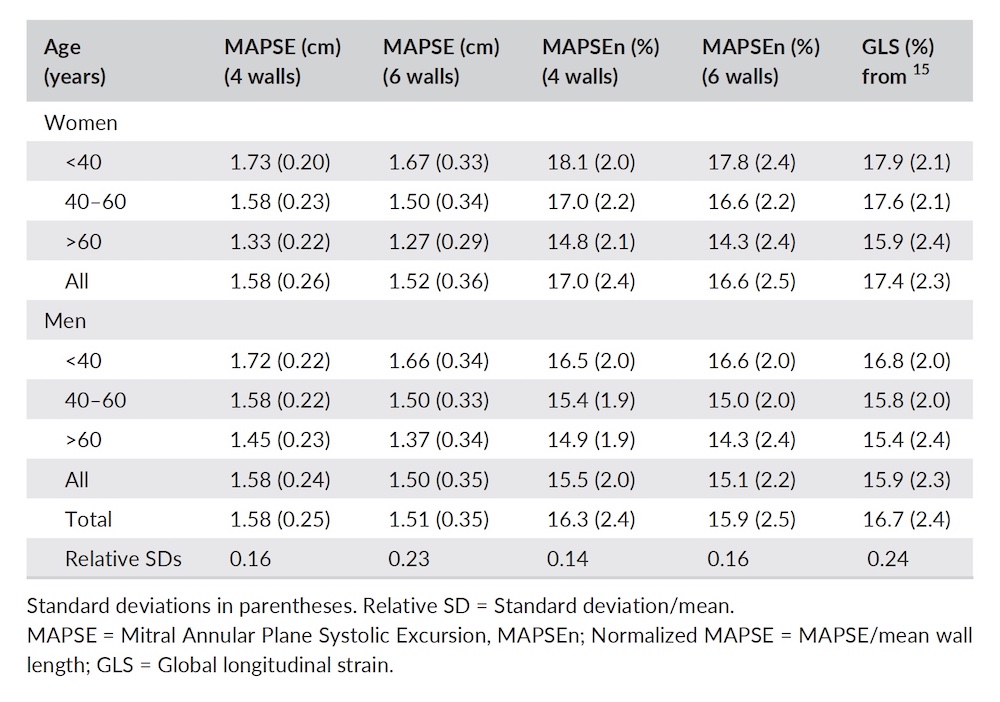

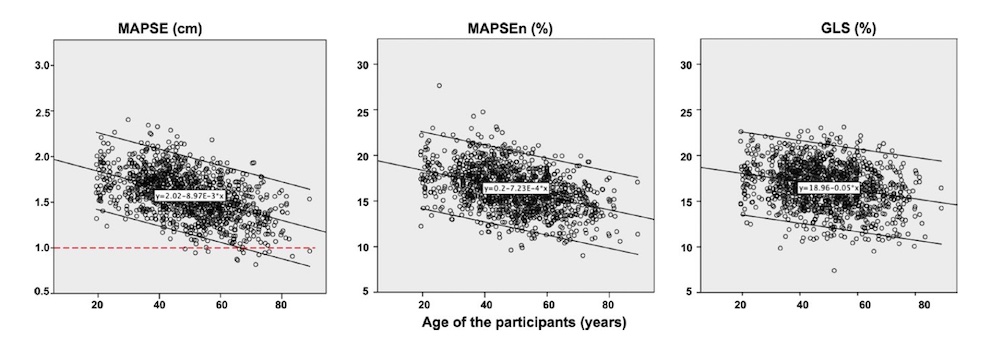

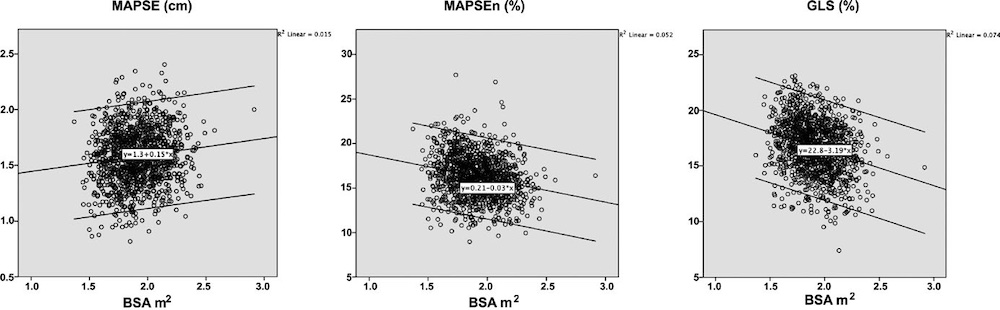

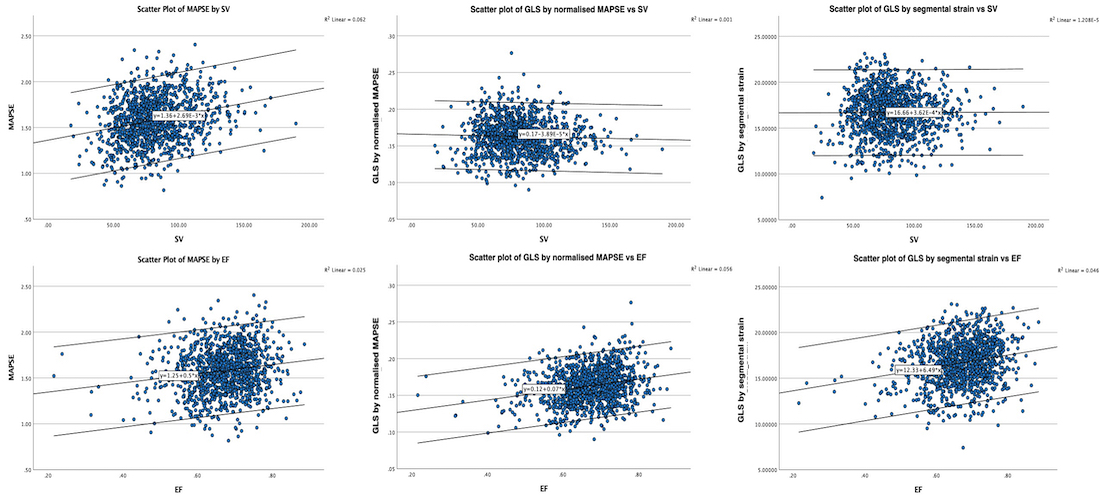

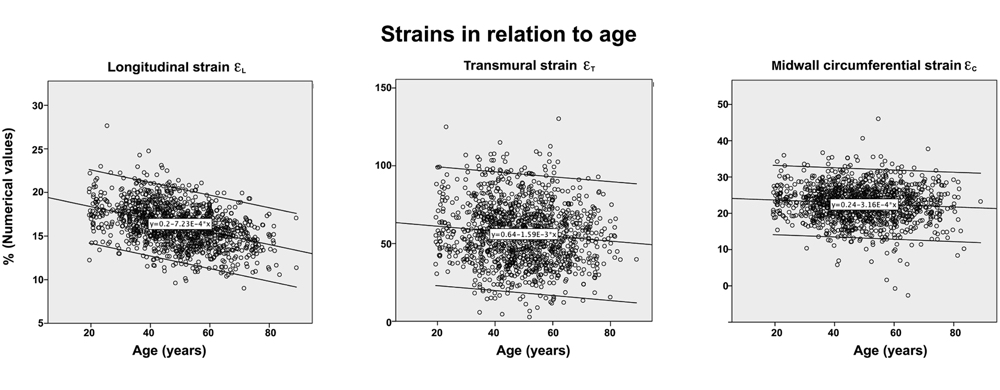

Dimensions of the ventricle is closely related to the functional measures. While the motion indices of displacement and velocity are dimension unrelated, strain and strain rate are relative deformation measures, and thus related to dimensions. Thus changes in dimensions will relate to changes in strain and strain rate. The HUNT study, being ta large study of normals has published normal values, related to age and gender (19):

Conventional left ventricular cross sectional measures from M-mode in the HUNT3 study by age and gender, raw and indexed for BSA. SD in parentheses.

Age (years) | N | IVSd | IVSd/BSA | LVIDd | LVIDD/BSA | FS (%) | LVPWd | LVPWd/BSA | RWT | RWT/BSA |

Women | ||||||||||

<40 | 207 | 7.5 (1.2) | 4.2 (0.6) | 49.3 (4.2) | 27.5 (2.6) | 36.6 (6.1) | 7.7 (1.4) | 4.3 (0.6) | 0.31 (0.05) | 0.17 (0.03) |

40–60 | 336 | 8.1 (1.3) | 4.5 (0.7) | 48.8 (4.5) | 27.3 (2.8) | 36.5 (6.9) | 8.3 (1.3) | 4.6 (0.7) | 0.33 (0.05 | 0.19 (0.03) |

> 60 | 118 | 8.9 (1.4) | 5.1 (0.8) | 47.8 (4.8) | 27.4 (3.1) | 36.0 (9.1) | 8.7 (1.4) | 5.1 (0.8) | 0.37 (0.07) | 0.22 (0.04) |

All | 661 | 8.1 (1.4) | 4.5 (0.8) | 48.8 (4.5) | 27.4 (2.8) | 36.4 (7.1) | 8.2 (1.4) | 4.6 (0.8) | 0.34 (0.06) | 0.19 (0.04) |

Men | ||||||||||

<40 | 128 | 8.8 (1.2) | 4.3 (0.6) | 53.5 (4.9) | 26.1 (2.6) | 35.5 (6.9) | 9.2 (1.3) | 4.5 (0.7) | 0.34 (0.06) | 0.17 (0.03) |

40–60 | 327 | 9.5 (1.4) | 4.6 (0.7) | 53.0 (5.5) | 26.0 (3.0) | 35.8 (7.4) | 9.7 (1.4) | 4.7 (0.7) | 0.37 (0.07) | 0.18 (0.03) |

> 60 | 150 | 10.1 (1.6) | 5.1 (0.9) | 52.1 (6.4) | 26.3 (2.9) | 36.0 (8.0) | 10.0 (1.3) | 5.1 (0.7) | 0.39 (0.07) | 0.20 (0.04) |

All | 605 | 9.5* (1.5) | 4.6† (0.8) | 52.9* (5.6) | 26.0† (2.9) | 35.8 (7.5) | 9.6* (1.4) | 4.7† (0.7) | 0.37 (0.07) | 0.18 (0.04) |

Total | 1266 | 8.7‡ (1.6) | 4.6 (0.8) | 50.8‡ (5.4) | 26.7 (2.9) | 36.1 (7.3) | 8.9 (1.6) | 4.7 (0.7) | 0.35 (0.07) | 0.18 (0.04) |

*p<0.001 compared to women. †p<0.01 compared to women. ‡Overall p<0.001 (ANOVA) for differences between age groups. RWT: relative wall thickness.

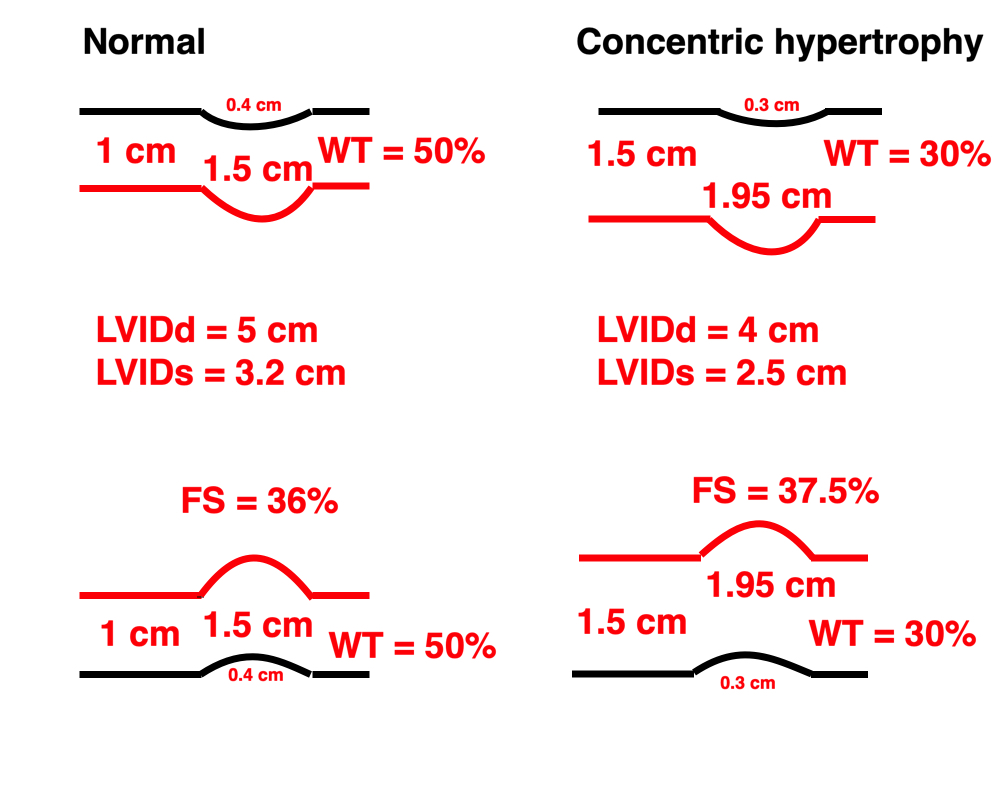

Wall thicknesses and LVIDD correlated with BSA (R from 0.41 - 0.48), Thus, all values were consistently higher in men due to this. FS, of course, did not correlate with BSA, and was thus gender independent. Wall thicknesses increased with age (R=0.33), and LVIDD decreased with age, as opposed to older studies (34, 35), possibly because of their smaller size.

FS remained constant between age groups, in accordance with other studies.

The values are M-mode derived.

In HUNT3, the upper normal cut off for RWT would be 0.49, which is relevan for M-mode derived values.

Relative wall thickness is generally considered to be a body size independent measure, as both wall thicknesses and LVIDD are body size dependent, the RWT, supposedly, is normalised for heart size, and hence, for body size. Interenstingly, in the HUNT study this was not the case, although correlation with BSA was very modest (R=0.18). This probably do not warrant normalising RWT for BSA. More pronounced was correlation with age (R=0.34), increasing from 0.31 to 0.37 in women, and from 0.34 to 0.39 in men. For M-mode derived values this means that the cut off for RWT would be 0.51 in the upper age groups, for both sexes.

The age dependency is a logical consequence of the unchanged LVIDd and increasing wall thickness, and has been shown also previously (33).

Relation of RWT and BSA in HUNT3. This shows that RWT is not perfectly aligned with body size. | RWT and age in HUNT3. This shows a more marked dependence of RWT and age, so age related normal values is probably warranted. |

Comparing with the values from HUNT4 (249), which were measured in 2D the values according to aghe and sex can be found in the original publication.:

Age (years) | IVSd (mm) | LVIDd (mm) | LVIDs (mm) | FS (%) | LVPWd (mm) | RWT |

Women | ||||||

20 - 39 | 6.8 (1.2) | 49 (4) | 33.3 (4.0) | 0.32 | 6.6 (0.9) | 0.27 |

40 - 59 | 7.4 (1.3) | 48 (4) | 33.0 (3.7) | 0.31 | 6.9 (1.0) | 0.30 |

60 - 79 | 8.1 (1.5) | 45 (4) | 30.9 (4.2) | 0.31 | 7.5 (1.1) | 0.35 |

> 79 | 8.2 (1.0) | 41 (4) | 28.1 (3.0) | 0.31 | 7.7 (1.2) | 0.39 |

All | 7.7 | 47 | 32 | 0.32 | 7.2 | 0.32 |

Men | ||||||

20 - 39 | 7.9 (1.3) | 52 (4) | 35.2 (4.3) | 0.32 | 7.3 (1.0) | 0.29 |

40 - 59 | 8.7 (1.3) | 52 (5) | 35.9 (4.5) | 0.31 | 8.0 (1.2) | 0.32 |

60 - 79 | 9.2 (1.5) | 50 (5) | 33.9 (4.8) | 0.32 | 8.3 (1.2) | 0.35 |

> 79 | 9.3 (1.7) | 48 (6) | 34.6 (3.9) | 0.28 | 8.2 (0.8) | 0.36 |

All | 8.9 | 51 | 34.9 | 0.32 | 8.1 | 0.33 |

Total | 8.2 | 49 | 33.3 | 0.31 | 7.6 | 0.33 |

Values are taken from (249). All age differences were significant) Values were corrected for the numbers in each age class before averaging by me. FS and RWT are calculated by me from the basic measurements, and likewise corrected for numbers.

What we see is that the M-mode derived values of HUNT3, are slightly higher than the 2D derived values from HUNT 4, for wall thickness and chamber diameter. The sex and age distribution of the subjects are about the same in both studies, although the age related decline in LVIDd is steeper in HUNT4.

The NORRE study (250), however, had intermediate values; IVSd 8.6 mm and LVPWd 8.8 mm, although closer to HUNT3. LVIDd was fairly close in HUNT 3 and 4, somewhar smaller in NORRE (44.3 mm), age related values for linear dimensions are not given. Mean FS in NORRE can be calculated to 33%.

Thus, the NORRE study seems to confirm the bias between M-mode and 2D derived measures, being lower than HUNT3.

This consistent with a statistical bias towards skewed measures in M-mode, which tend to be corrected in 2D (224), so values in HUNT3 may be valid for M-mode measures, but will overestimate the true values, and is not transferable to 2D derived measures.

|

|

|

Reconstructed M-mode with a fairly straight cross angle between the M-mode line and the LV long axis. | Reconstructed M-mode from the same loop, but with the M-mode line crossing the LV long axis at a skewed angle, showing thicker walls and wider cavity, due to the angulation. | B-mode measurement across the ventricle in the same loop. Wall thicknesses are similar to the straight angle M-mode. LVIDd (and hence, RWT) are slightly different as the measurement line does not cross the posterior wall at exactly the same point. |

However, the relation between values, and relations with age, seems to be valid across the methods. Decreasing LVIDd but increasing WT with increasing age was found in both HUNT3 and 4, so these relations are not method specific. FS do not seem to differ very much between age groups in either study. Theoretically, skewed measurements would not affect the ratio of the measured values (RWT and FS). However, as we see, both RWT and FS are slightly lower in HUNT4, and in the NORRE study the mean FS was 0.33 as well. Skewed measures should not give increased ratios per se, but, angulation will also be affected by the AV plane motion, so there are more systematic errors than just angulation.

The cut off for RWT in HUNT 4 would be ca 0.47 over all. Mean RWT in the NORRE study can be calculated to 0.39, higher than both HUNT 3 and 4, confirming that the cut off seems to be to low. While RWT increases with age in both studies. As RWT is derived from wall thicknesses which increases significant with age (249) and LVIDd which decreases significant with increasing age, (249), the increase in RWT has to be significant as well.

Increasing wall thickness and LVIDd with higher BSA, and relative wall thickness thus also have to increase with increasing age as diameter decreases and wall thickness increases in both studies. The cut off for RWT in HUNT 4 would be ca 0.47 over all, and increasing by age, possibly around 0.50 for the upper age groups, still higher than previous normal cut off values (224).

The age relation is not taken into account in current guidelines, but as upper normal limit increases by age, age related values should be warranted.

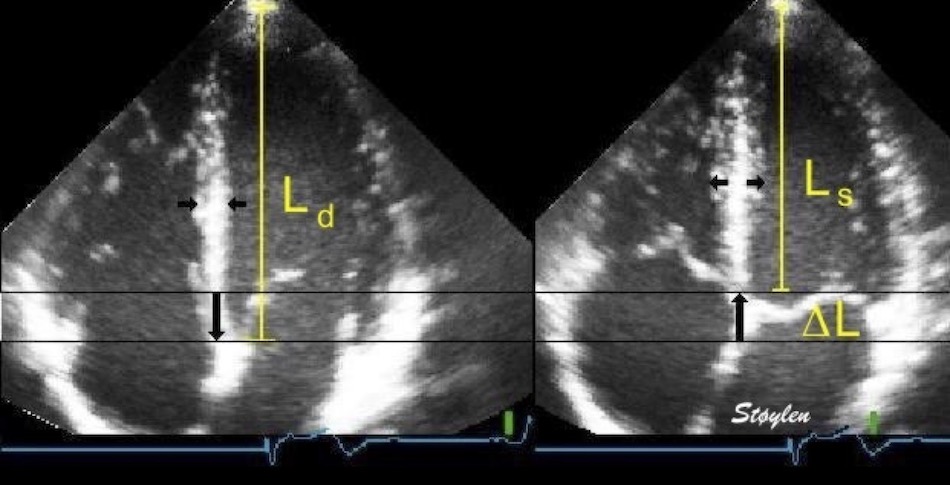

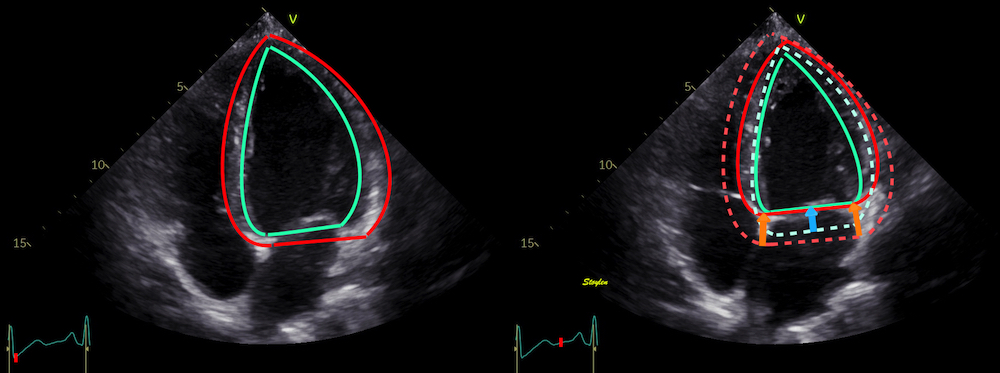

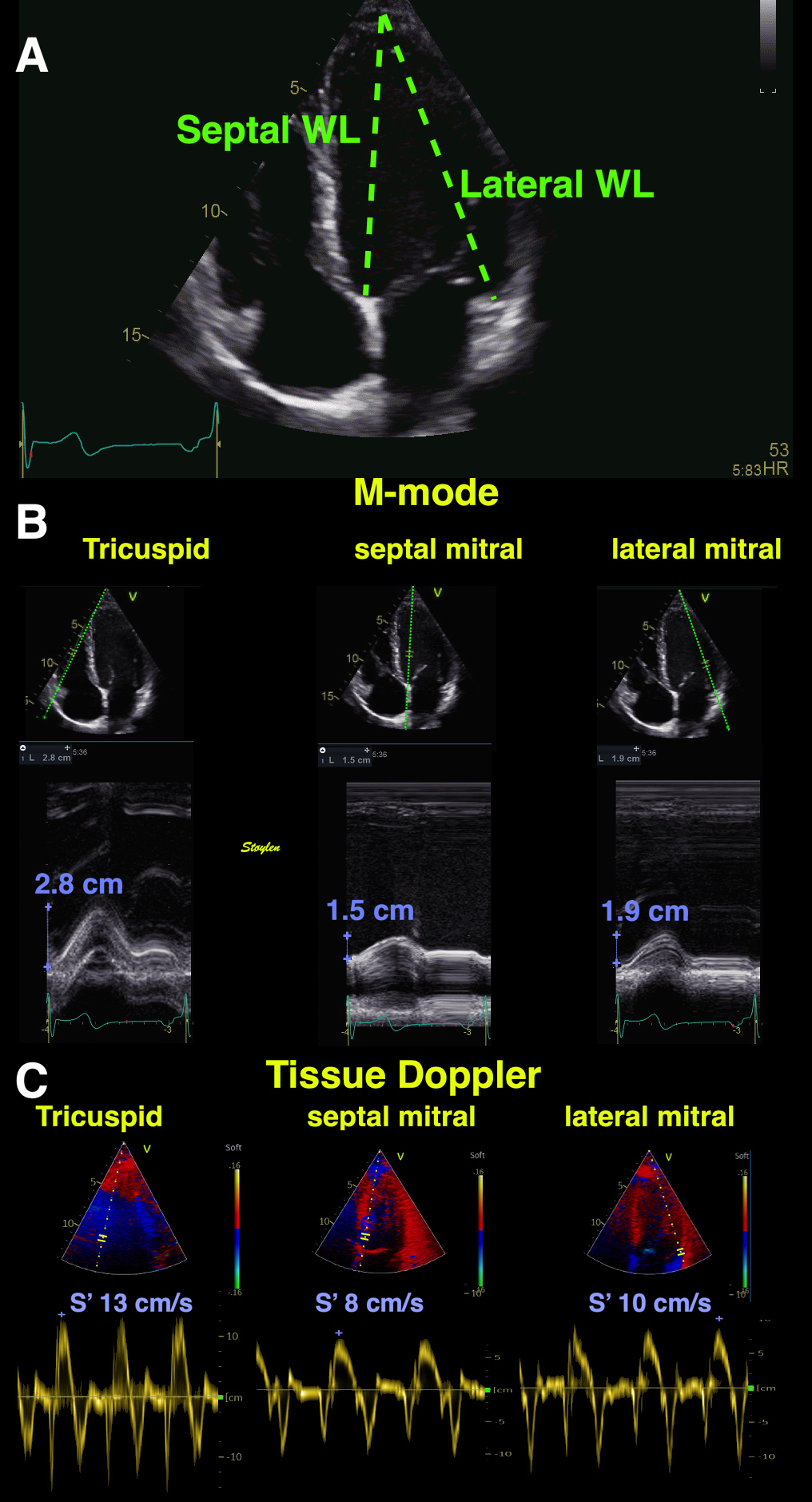

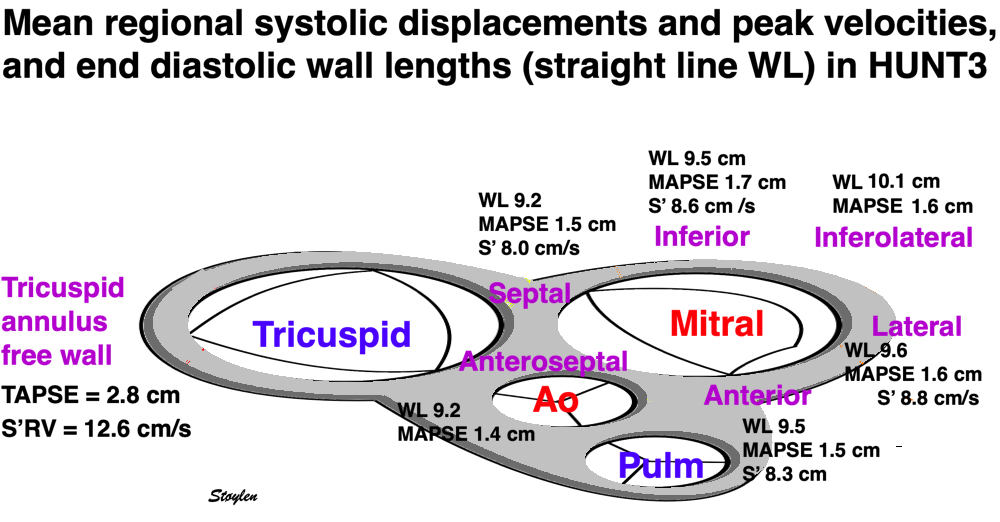

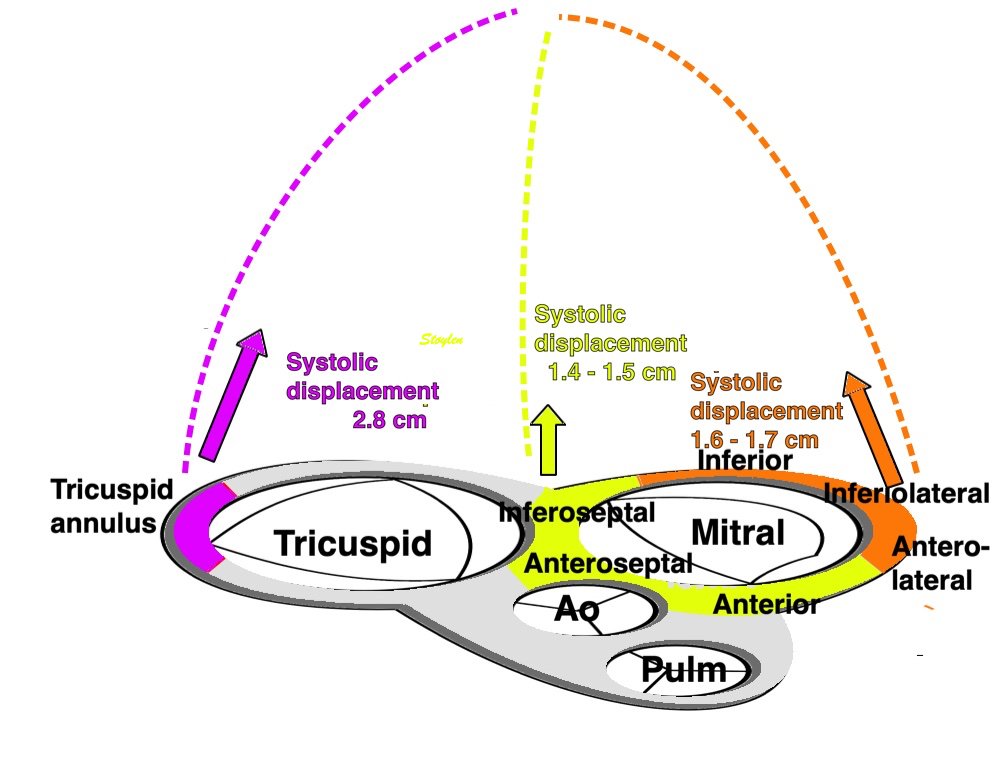

Left ventricular length and external diameter is also important in an evaluation of the total strain images. In the HUNT3 study, we initially measured wall length, from the mitral annulus to the apex, which will over estimate the LVL, but is proportional (19). Later, we refined this to an ellipsoid model, allowing to calculate the mid cavity LV length (65) as shown below.

|

|

Left ventricular length. Wall lengths were measured in a straight line (WL) in all six walls from the apex to the mitral ring. This wil underestimate true wall lengths (dotted, curved lines), but will be more reproducible, as the curvature may be somewhat arbitrary. LVL was calculated as mean of all four walls, thus overestmating true LVL (yellow line) slightly, but again the arbitrary placement in the middle of the ostium will result in lower reproducibility, while taking the mean of six measurements will increase it. | Ellipsoid model of the left ventricle. All basic measures are linear, and the ellipsoid model assumes symmetrical wall thickness, declining to half in the apex, mitral annular diameter constant; equal to ventricular end systolic diameter, as LV diameter decreased by 12.8% is systole while the fibrous mitral annulus may be assumed to be more constant. LVL is calculated by the pythagorean theorem, using 1/2 LVIDd plus 1/2 WTd. |

Left ventricular external diameter, is simply the sum of the wall thicknesses and LVIDd. From the geometric calculation, we found LV internal and external lengts (assuming apical wall thickness in both systole and diastole to be 50% of basal wall thickness:

Left ventricular wall length and external diameter by age and gender from the HUNT3 study, raw and indexed for BSA..

Age (years) | N | LVEDD (cm) | LVEDD/BSA (mm/m2) | LWVL (cm) | LWVL/BSA (cm/m2) | LVWL/LVEDD | LVELd (mm) | LVILd (mm) |

Women | ||||||||

<40 | 207 | 6.45 (0.48) | 35.9 (2.7) | 9.4 (1.6) | 5.23 (1.00) | 1.46 (0.26) | 91.0 (6.2) | 87.2 (6.1) |

40–60 | 336 | 6.52 (0.52) | 36.5 (3.2) | 9.1 (1,7) | 5.08 (0.95) | 1.40 (0.27) | 88.5 (6.0) | 84.3 (5.9) |

> 60 | 118 | 6.52 (0.52) | 37.7 (3.5) | 8.9 (1.3) | 5.08 (0.79) | 1.36 (0.23) | 85.0 (5.9) | 80.1 (5.9) |

All | 661 | 6.51 (0.51) | 36.5 (3.2) | 9.1 (1.6) | 5.13 (0.93) | 1.41 (0.27) | 88.7 (6.4) | 84.6 (6.4) |

Men | ||||||||

<40 | 128 | 7.16 (0.53) | 35.0 (2.9) | 10.3 (1.7) | 5.02 (0.88) | 1.44 (0.25) | 99.6 (6.4) | 95.0 (6.4) |

40–60 | 327 | 7.22 (0.58) | 35.0 (3.2) | 10.0 (1.8) | 4.84 (0.89) | 1.39 (0.26) | 97.3 (7.4) | 92.5 (7.4) |

> 60 | 150 | 7.22 (0.68) | 36.5 (3.1) | 9.5 (1.8) | 4.80 (0.97) | 4.80 (0.97) | 92.1 (7.8) | 87.1 (7.8) |

All | 605 | 7.21 (0.59) | 35.3 (3.1) | 9.9 (1.4) | 4.86 (0.91) | 1.38 (0.27) | 96.5 (7.8) | 91.7 (7.8) |

Total | 1266 | 6.84 (0.65) | 36.0 (3.2) | 9.5 (1.8) | 5.00 (0.93) | 1.40 (0.27) | 92.4 (8.1) | 88.0 (7.9) |

SD in perentheses, LVELd: Diastolic external length LVILd diastolic internal length. p < 0.001.

It is logical that LVEDd increased both with BSA (R=0.60) and modestly with age (R=0.11, the unchanged LVIDd being part of it, dilutes the effect of wall thickness) (19).

Left ventricular length, on the other hand, increased with BSA (R=0.29), but decreased with age (R = -0.12).

Left ventricular external diameter, is calculated from the published values as the sum of the wall thicknesses and LVIDd. Values were corrected for the numbers in each age class by me.

Values from HUNT4 , measured in 2D the values according to age and sex can be found in the original publication (249).: LV lengths were exported from the volumetry tracings in 2D (Dalen H personal communication), meaning they represent inner length.

Age (years) | IVSd (mm) | LVIDd (mm) | LVPWd (mm) | LVEDd (mm) | LVILd-4ch (cm) | LVILd2ch (cm) |

Women | ||||||

20 - 39 | 6.8 (1.2) | 49 (4) | 6.6 (0.9) | 62.4 | 8.5 (0.6) | 8.6 (0.8) |

40 - 59 | 7.4 (1.3) | 48 (4) | 6.9 (1.0) | 62.3 | 8.3 (0.6) | 8.4 (0.6) |

60 - 79 | 8.1 (1.5) | 45 (4) | 7.5 (1.1) | 60.6 | 7.9 (0.6) | 7.9 (0.6) |

> 79 | 8.2 (1.0) | 41 (4) | 7.7 (1.2) | 56.9 | 7.1 (0.5) | 7.3 (0.5) |

All | 7.7 | 47 | 7.2 | 61.5 | 8.1 | 8.2 |

Men | ||||||

20 - 39 | 7.9 (1.3) | 52 (4) | 7.3 (1.0) | 67.2 | 9.7 (0.6) | 9.7 (0.6) |

40 - 59 | 8.7 (1.3) | 52 (5) | 8.0 (1.2) | 68.4 | 9.2 (0.6) | 9.4 (0.7) |

60 - 79 | 9.2 (1.5) | 50 (5) | 8.3 (1.2) | 67.5 | 8.9 (0.6) | 8.9 (0.6) |

> 79 | 9.3 (1.7) | 48 (6) | 8.2 (0.8) | 65.5 | 8.5 (0.5) | 8.4 (0.5) |

All | 8.9 | 51 | 8.1 | 68.0 | 9.1 | 9.2 |

Total | 8.2 | 49 | 7.6 | 64.3 | 8.5 | 8.6 |

Values are taken from (249). All age differences were significant, although not tested for LVEDD. As in HUNT3, we se that the age effect on LVEDd is diluted, by the decreasing LVIDd and increasing WT.

In HUNT3, the mean left ventricular internal length was calculated from wall lengths to 88 mm. In HUNT4, the internal LV length was 85 mm.

Disregarding the separate age group > 80, which has no comparable group in HUNT3 (and which are small), we see that internal length decline from 87 - 80 mm in women and 95 - 87 in men, while in HUNT 4 the lengths declined from 85 - 79 mm in women and 97 - 89 in men.

Thus both studies confirm a decline in both internal diameter and length with increasing age.

Fundamental findings are summarised below:

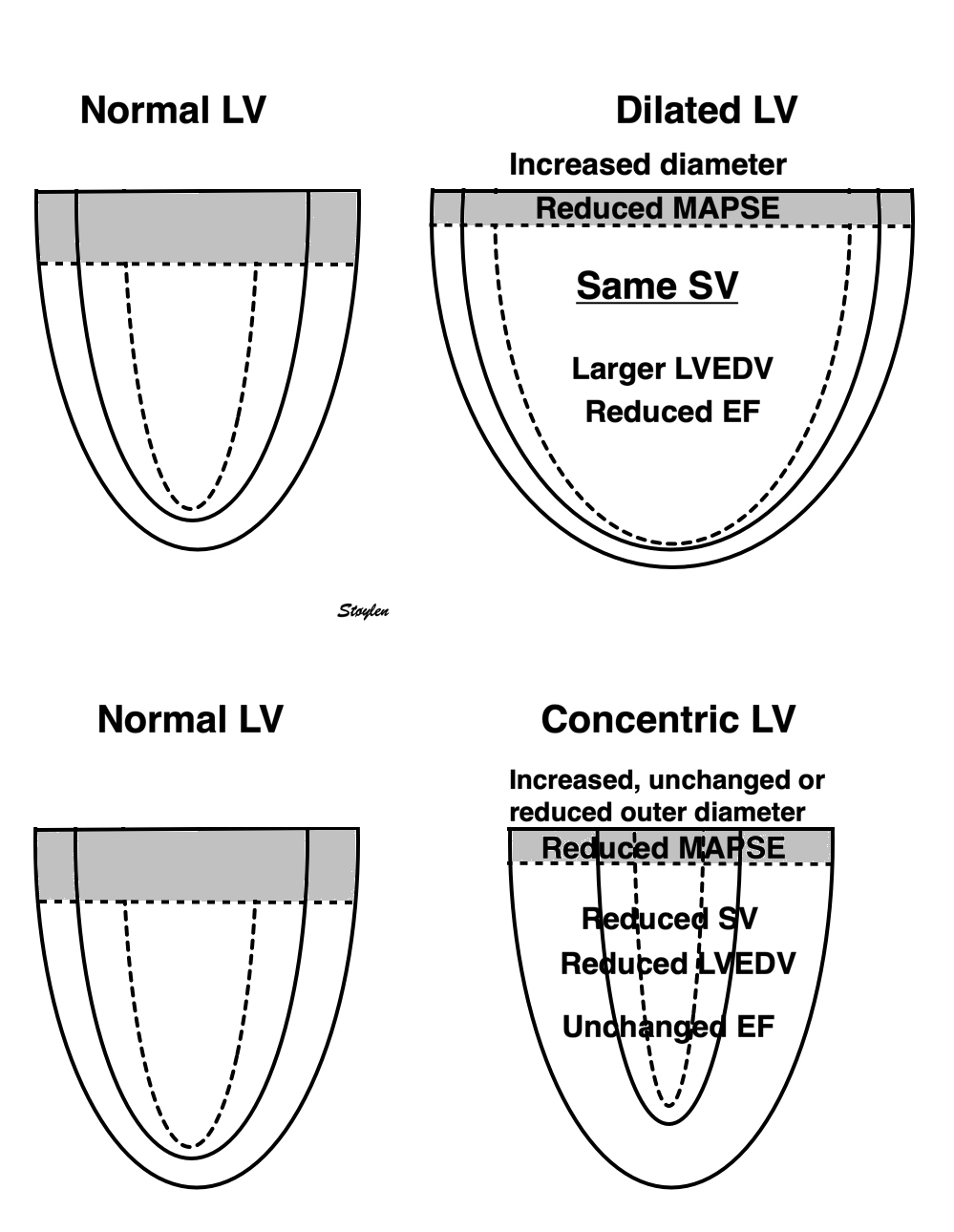

Fundamental findings in the HUNT study: With increasing BSA, both wall thickness, internal diameter (and hence, external diameter) and relative wall thickness increase, showing that neither measure is independent of body size (or heart size). The length / external diameter, however, remains body size independent, being a true size independent measure. Differences are exaggerated for illustration purposes. | With increasing age, both wall thickness (and hence, external diameter) increase, while internal diameter is age independent. Left ventricular length decreases, and hence length / external diameter decreases, and i a measure of age dependent LV remodeling. This has implication for LV mass calculation. Dimension changes are exggerated for illustration puposes. |

The ratio L/D did not correlate with BSA in HUNT3, was near gender independent (although the difference was significant due to the high numbers), but declined somewhat more steeply with age (R = -0.17). In HUNT4, the ratio between external diameter and internal length was 1.32 in women and 1.34 in men, but declined with age.

This has some important corollaries:

Applying the linear measures to an elliptical model of the left ventrcle, allowed the estimation of LV volumes (471).

Ellipsoid model of the left ventricle. All basic measures are linear, and the ellipsoid model assumes symmetrical wall thickness, declining to half in the apex, mitral annular diameter constant; equal to ventricular end systolic diameter, as LV diameter decreased by 12.8% is systole while the fibrous mitral annulus may be assumed to be more constant.

The ellipsoid model has some limitations. Being symmetric, it do not conform totally to the shape of the LV, which is assymmetric, as in other model studies.

An indication of this was that while all linear measurements were near normally distributed, there was a greater skewness in the calculated volunes:

Comparing skewnesses of the distributions of the linear measures (which is small), with the calculated volumes (which is significantly (greater), seems to indicate a systematic error in the volume data from the model.

Despite this, findings were interesting.

Age | LVEDV(ml) | SV(ml) | EF(%) | Myocardial volume d (ml) |

Women | ||||

<40 | 111.6(21.6) | 76.3(16.4) | 68(6) | 87.0 (19) |

40-60 | 106.9(21.7) | 72.7(17.0) | 68(6) | 92.8 (19.6) |

>60 | 97.9(19.7) | 65.4(16.9) | 66(9) | 95.6 (18.9) |

Total | 106.8(21.8) | 72.6(17.3) | 68(6) | 91.4 (19.6) |

Men | ||||

<40 | 144.8(30.5) | 96.1(22.9) | 66(8) | 125.3 (23.6) |

40-60 | 138.1(31.1) | 92.2(23.8) | 67(8) | 129.7 (25.3) |

>60 | 126.3(33.7) | 84.1(25.7) | 66(8) | 128.2 (26.8) |

Total | 136.6(32.2) | 91.0(24.4) | 67(8) | 128.4 (25.3) |

All | 121.1(31.1) | 81.4(22.9) | 67(8) | 101.4 (27.9) |

LV volumes in HUNT4

Volumes in HUNT 4 are 2D measurement derived, values given are taken from (249).

Comparing with the values from HUNT4 (249), which were measured in 2D, the values according to age and sex can be found in the original publication.:

Age (years) | LVEDV(ml) | SV(ml) | EF(%) |

Women | |||

20 - 39 | 114 (26) | 68 | 60 |

40 - 59 | 102 (19) | 62 | 61 |

60 - 79 | 84 (19) | 51 | 60 |

> 79 | 67 (7) | 41 | 62 |

All | 94 | 57 | 61 |

Men | |||

20 - 39 | 145 (28) | 84 | 58 |

40 - 59 | 136 (29) | 81 | 60 |

60 - 79 | 119 (27) | 71 | 60 |

> 79 | 104 (18) | 62 | 59 |

All | 128 | 76 | 59 |

Total | 109 | 66 | 60 |

SV is calculated from EDV and ESV, corrected for the numbers in each age class before averaging.

Compared to the ellipsoid model from M-mode derived values, LVEDV is lower, but the relation to age, with declining values in increasing age are the same. This of course follows from the simultaneous age dependent decrease in both LVIDd and LVILd by age in both studies. Myocardial volume is not calculated in HUNT4.

The NORRE study shows even lower EDV, but LVEDV decrease with age too.

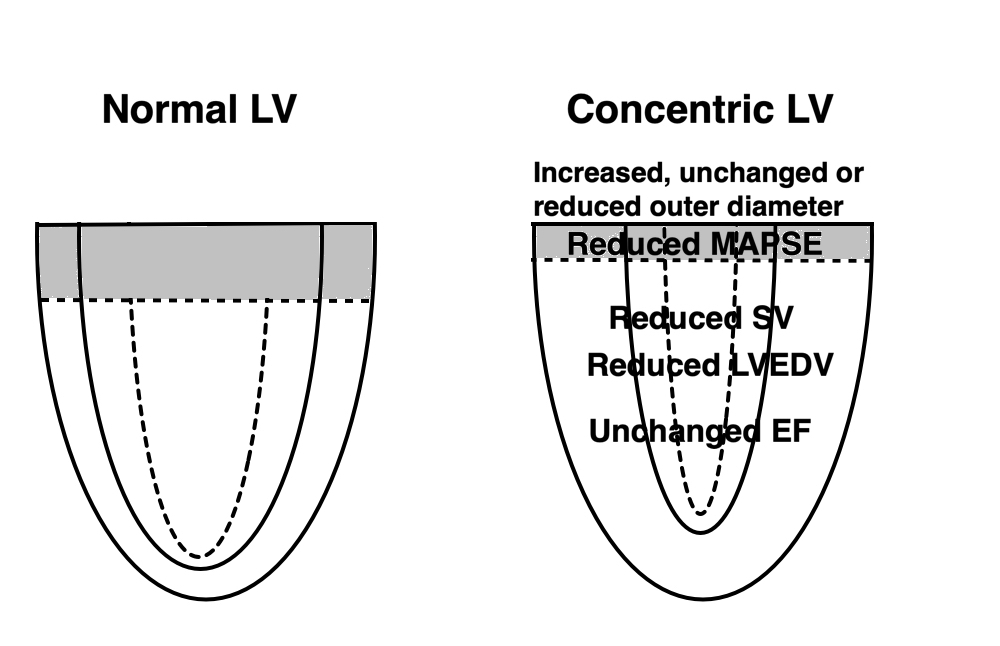

As we have already shown, left ventricular wall thickness increased with age, LV diameter was unchanged, while LV wall length decreased (19). However, LV volume increased by age (65), this effect being more profound in women.

Myocardial volumes were not calculated in HUNT4. The NORRE study gives increasing myocardial mass (which in practice is only myocardial volume × 1.05) in women, with mean 146 g in men and 112 g in women.

But tThe HUNT 3 population despite exclusion of patients with history or treatment for hypertension, had an increasing mean SBP and DBP with increasing age, due to an increasing number with BP above hypertensive levels:

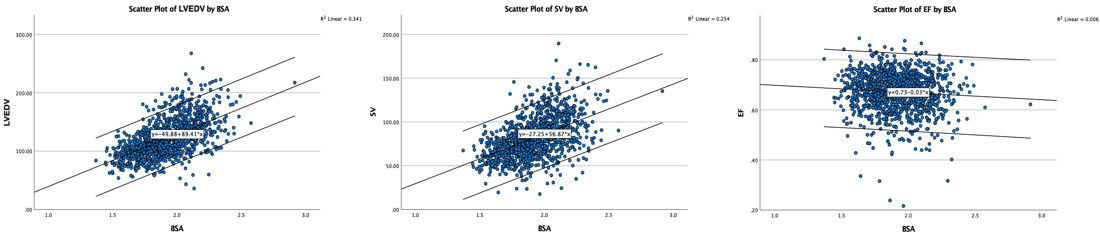

A: Mean BP showing an age related increase, above 60 about half is in the hypertensive level >140/90. B: LV volume in the different BP groups (results were not different if 140/90 was used). There is significant higher volumes in the >130/80 group, but in neither group was there any significant increase with increasing age.

There was a weak, but significant correlation of LV volume with age (R=0.14, p<0.001), but neither in linear regression nor partial coorrelation was there any significant increase with age, indicating that the age effect is mainly an BP effect.

Myocardial compressibility in relation to strains is discussed in the fundamental concepts section.

The volume ratio by strains is

![]()

Given myocardial incompressibility,

![]() ,

,

if the myocardium is compressed during systole,

![]() .

.

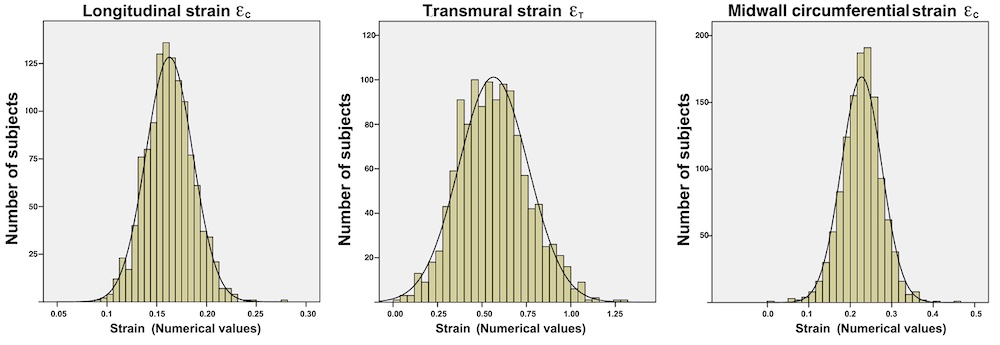

In the HUNT3 study, using the strain product on linear measures, the strain product, being equal to the volume ratio was 1.009 (1.0136 - 0.99851) using straight line wall measures (longitudinal strain -16.3%), and 0.9957 (1.003 – 0.98896) using mid ventricular line (longitudinal strain -17.1%). However, speckle tracking tends to measure higher GLS, because of the shortening due to inward tracking of the wall thickening, and wall thickening varies too much between studies to give any meaning of the strain product at all. The answer cannot be given by strains. For speckle tracking, we know that the resolution, and hence the tracking is different in the axial and lateral direction, so the values are not necessarily inter related in a proper way,

In the model study, however, myocardial volumes could be estimated. Here, we found a myocardial volume reduction in systole of 3.28 ml, or 2.5% of myocardial volume, 4.8% of SV.

This corresponds to a Vs/Vd of 0.975 (SD 0.112), 95%CI ((0.969-0.981) .

But as the model has limited accuracy, this is not normative either. Our main finding was that this compressibility, however, was not related to age, BP or BSA.

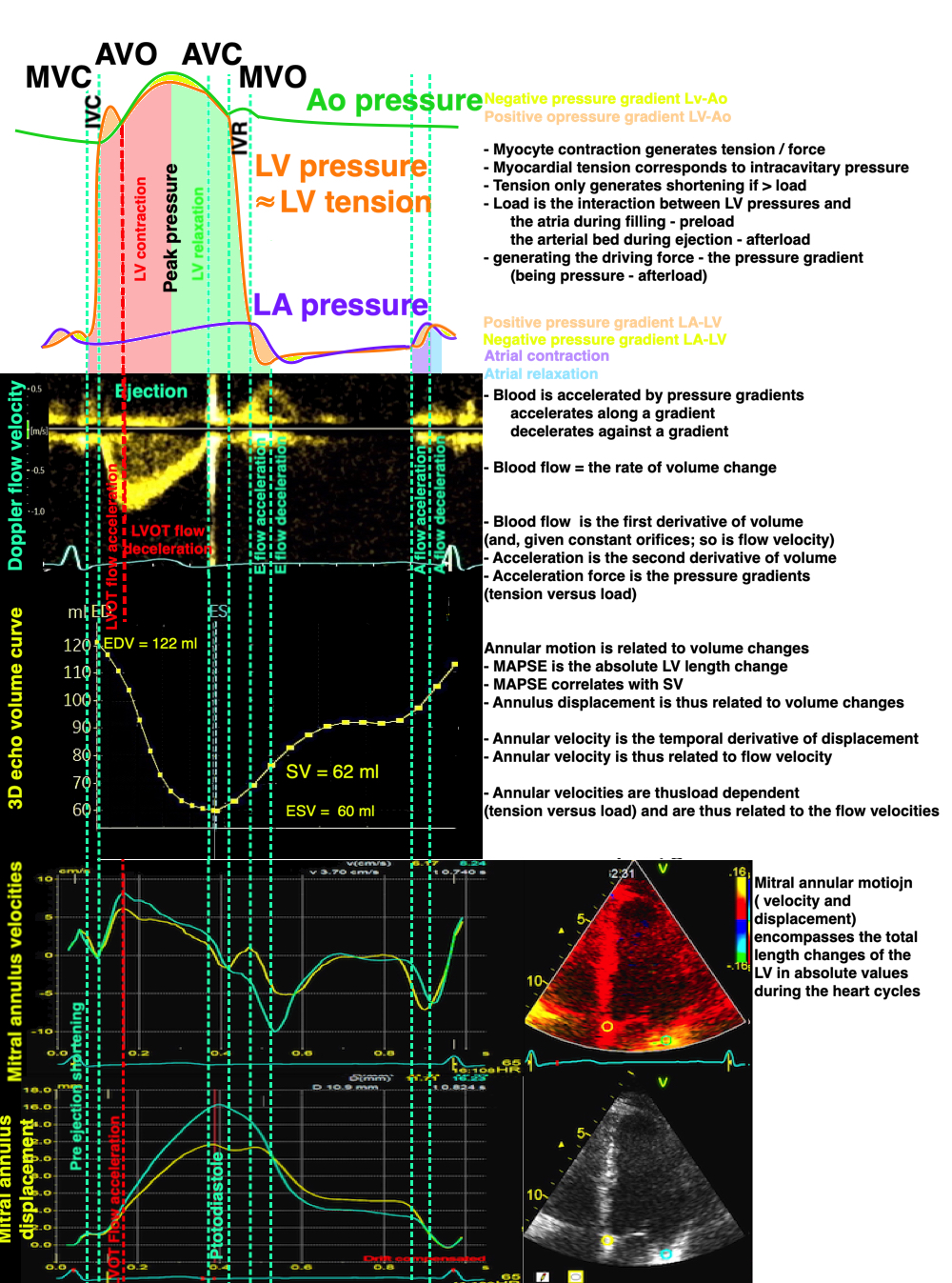

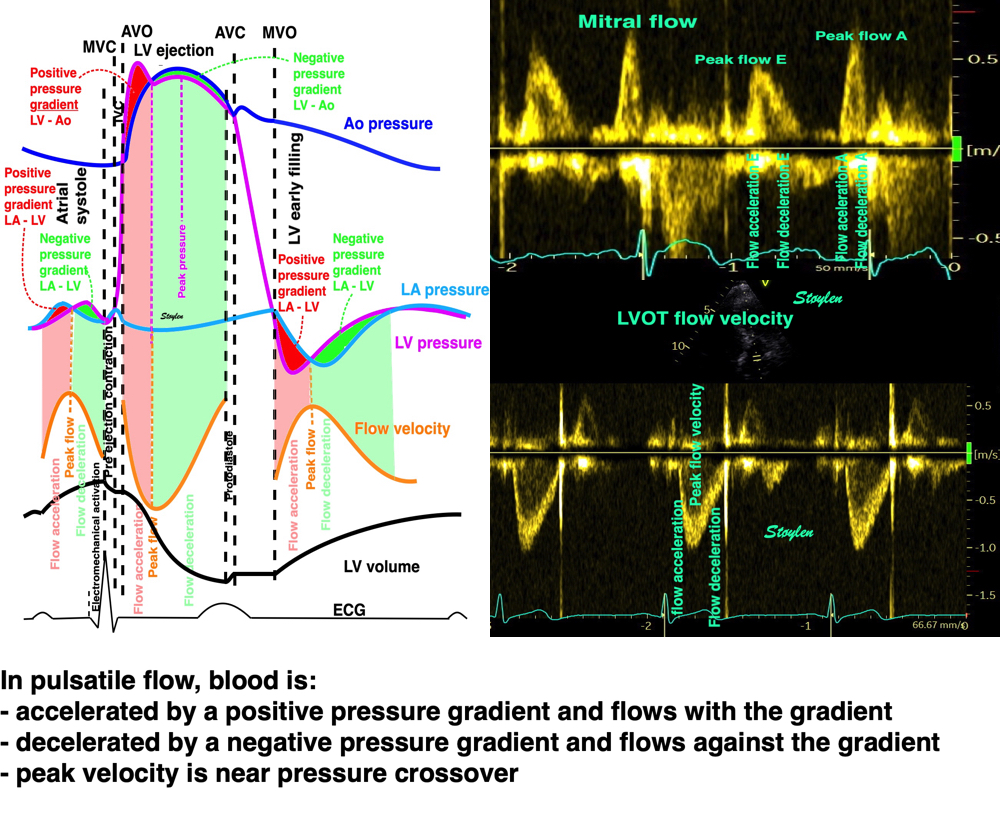

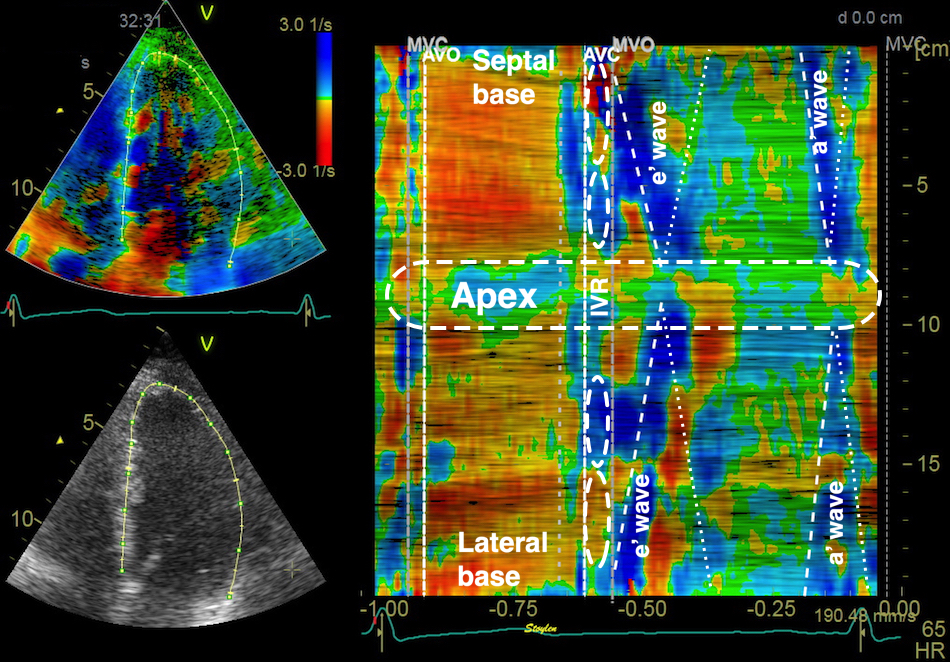

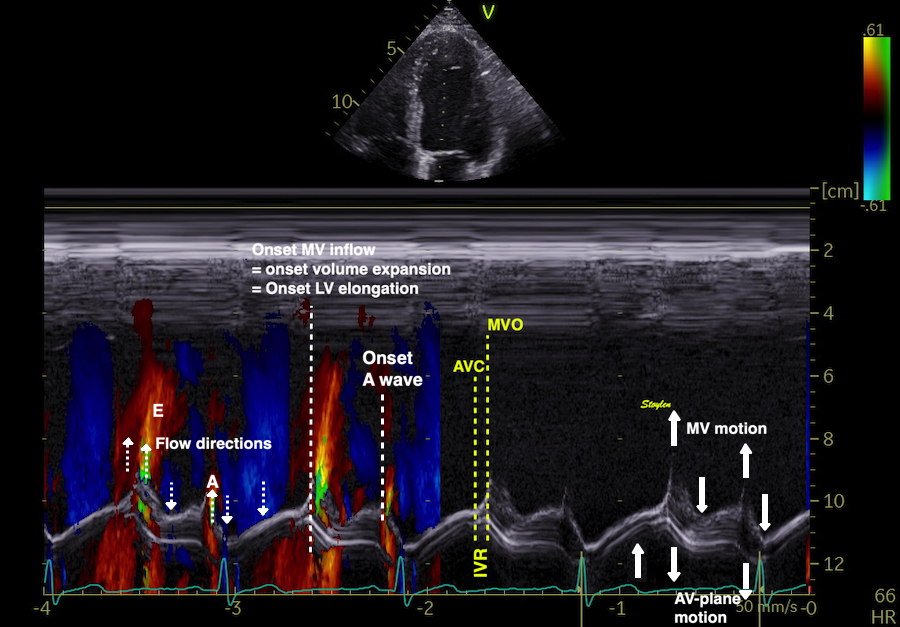

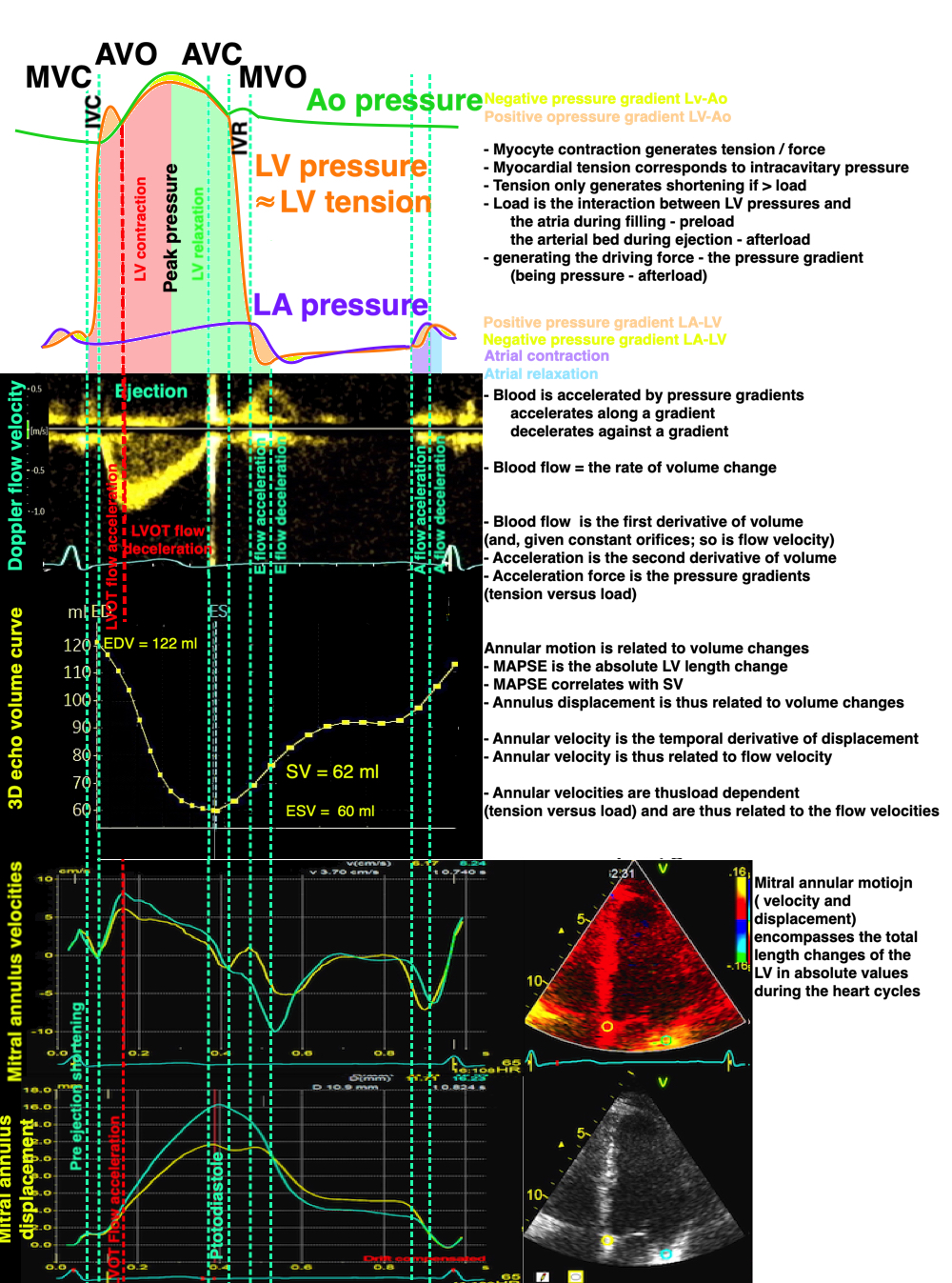

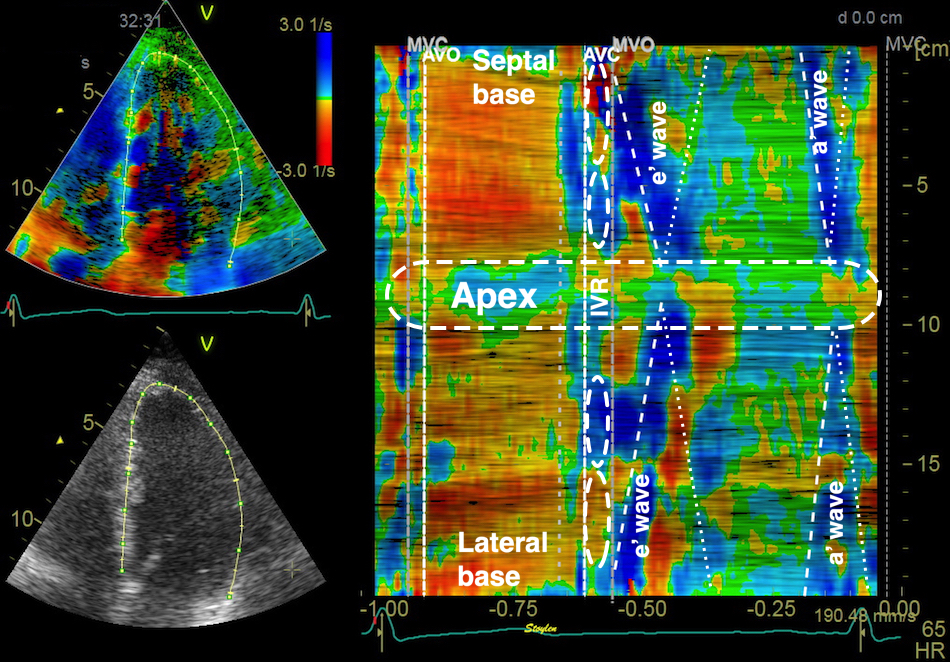

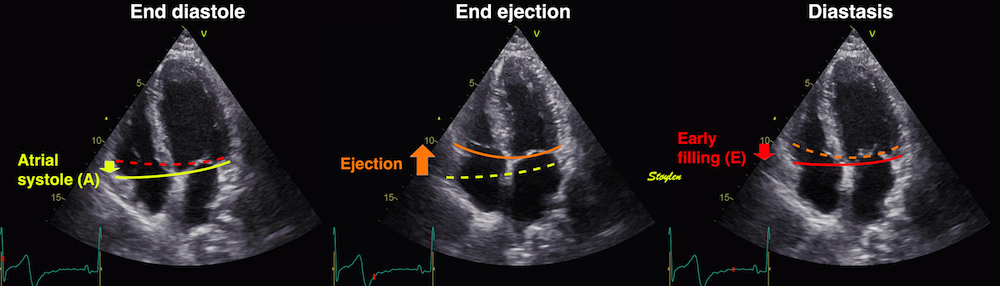

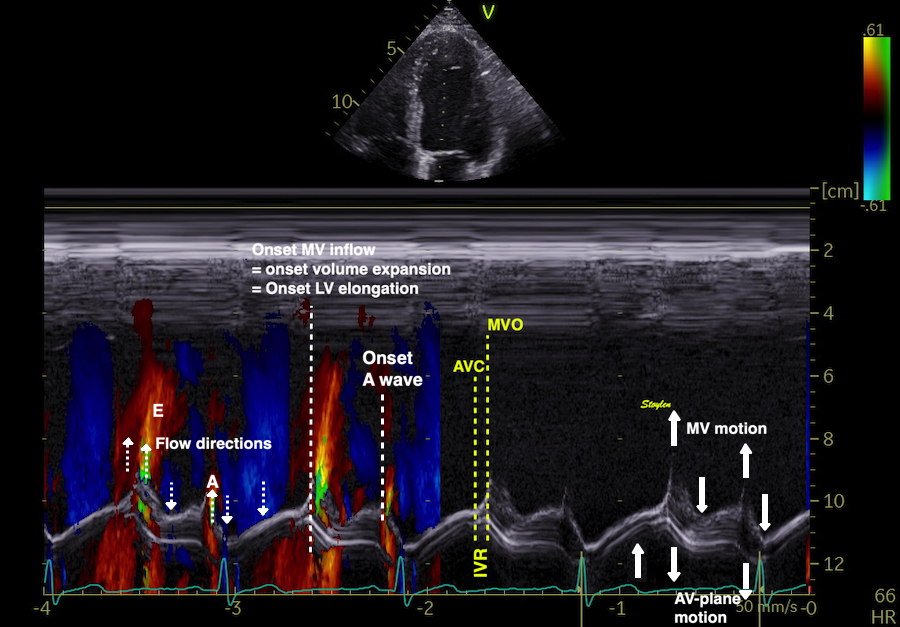

The full heart cycle is composed of the interactions between tissue deformation, flow and pressure in a complex manner. The intraventricular flow is an important part of the total picture.

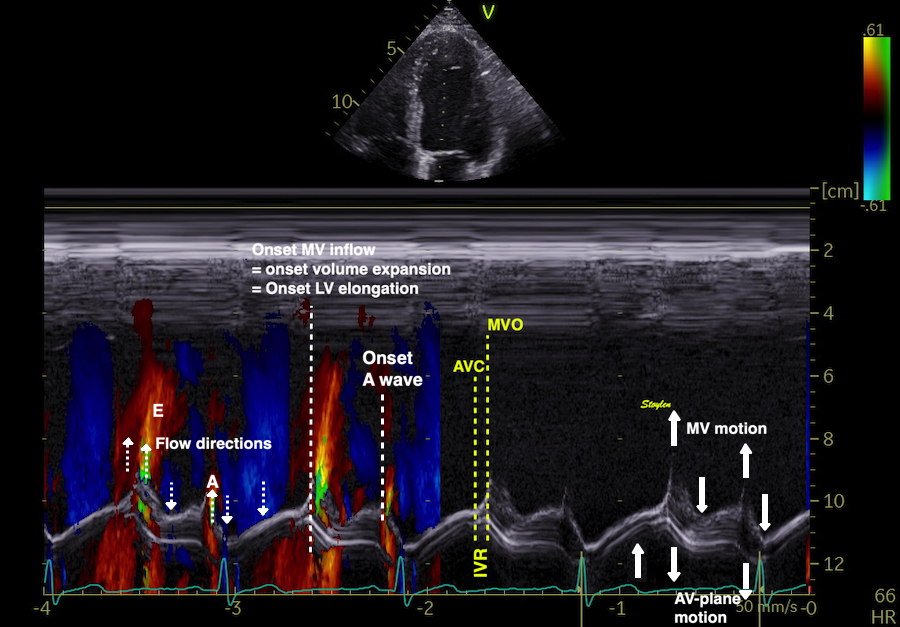

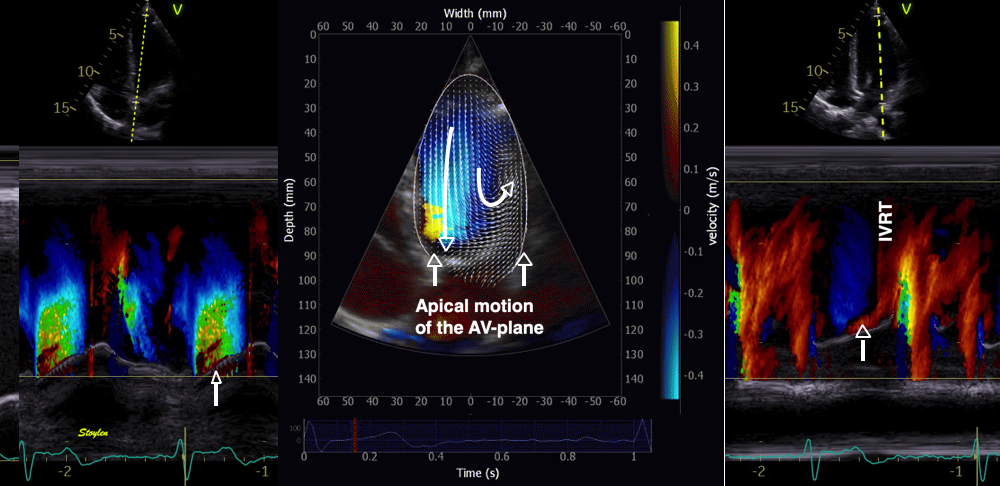

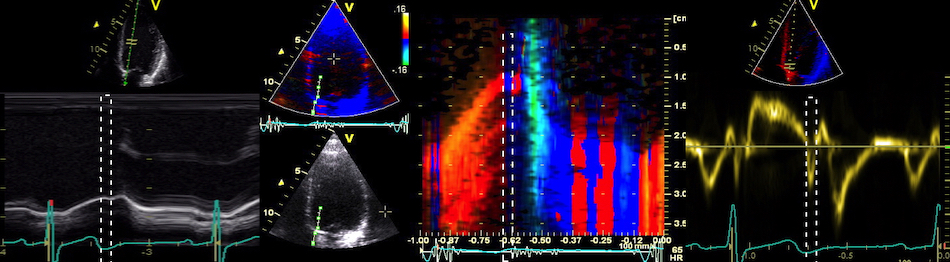

Combined high framerate tissue Doppler and vector flow imaging, showing a vortex in the LV. Image courtesy of Annichen S Daae.

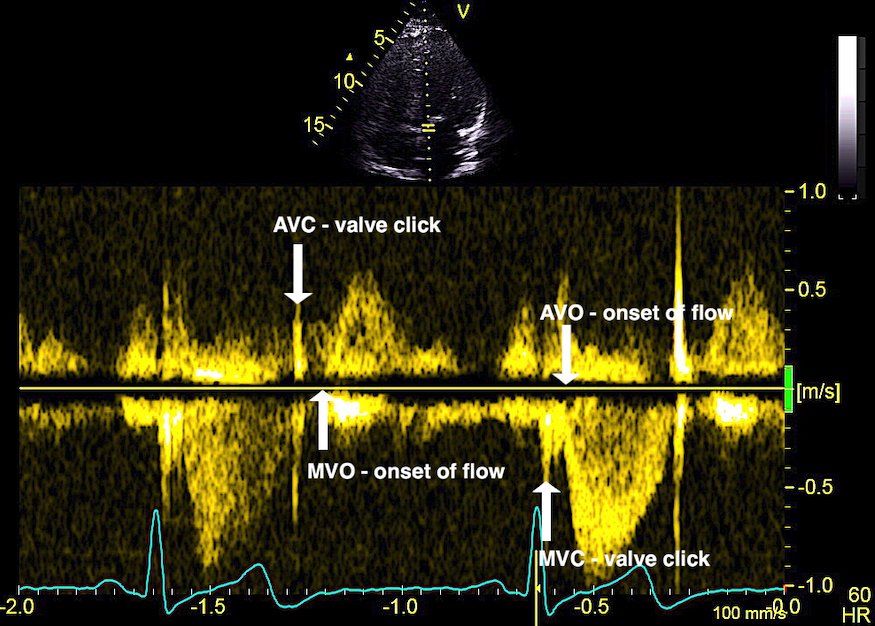

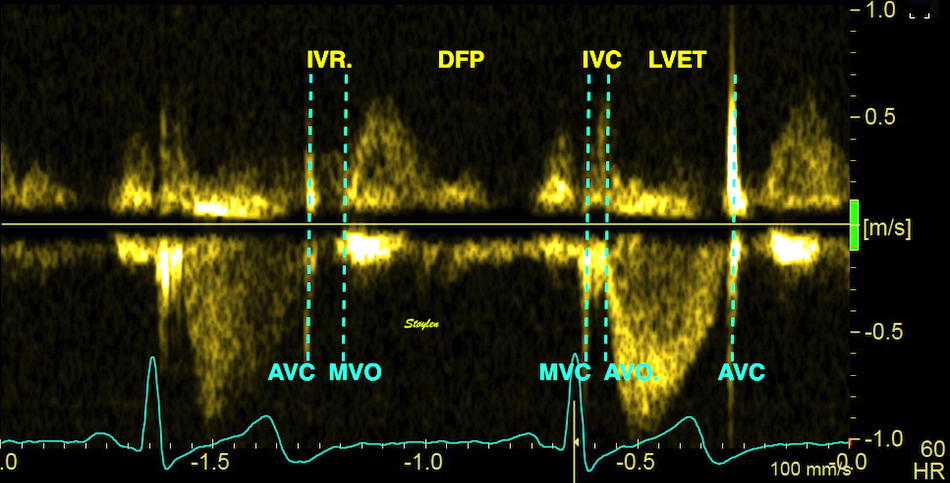

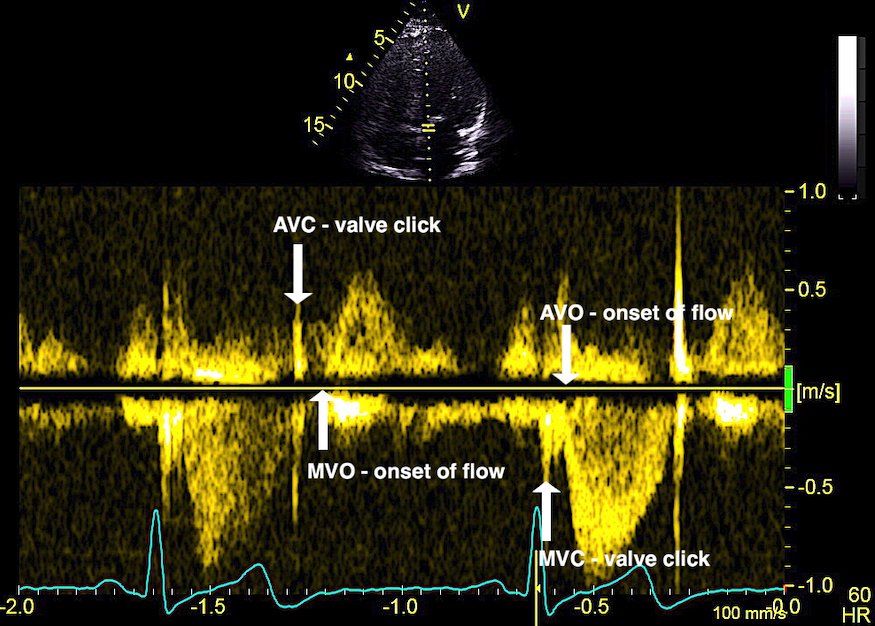

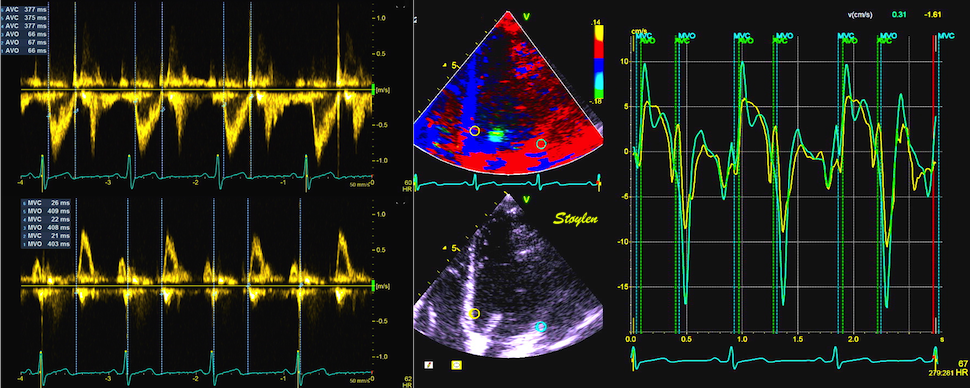

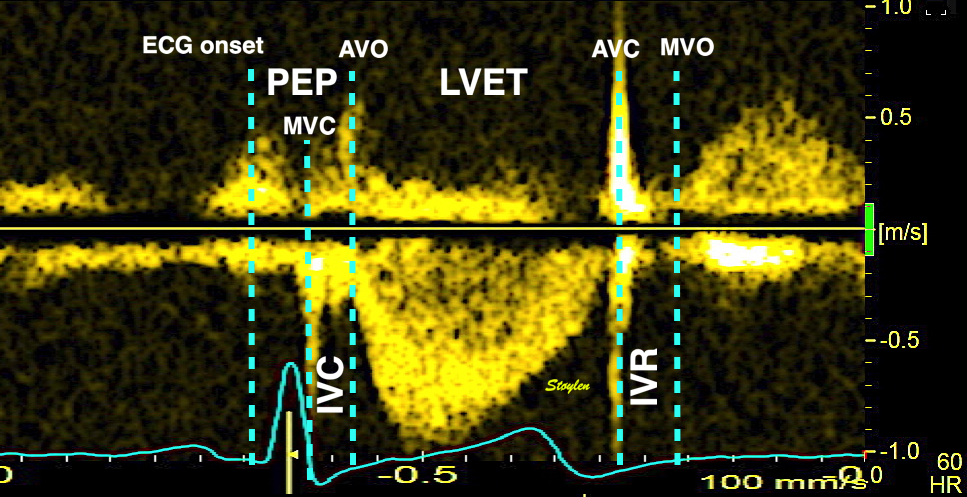

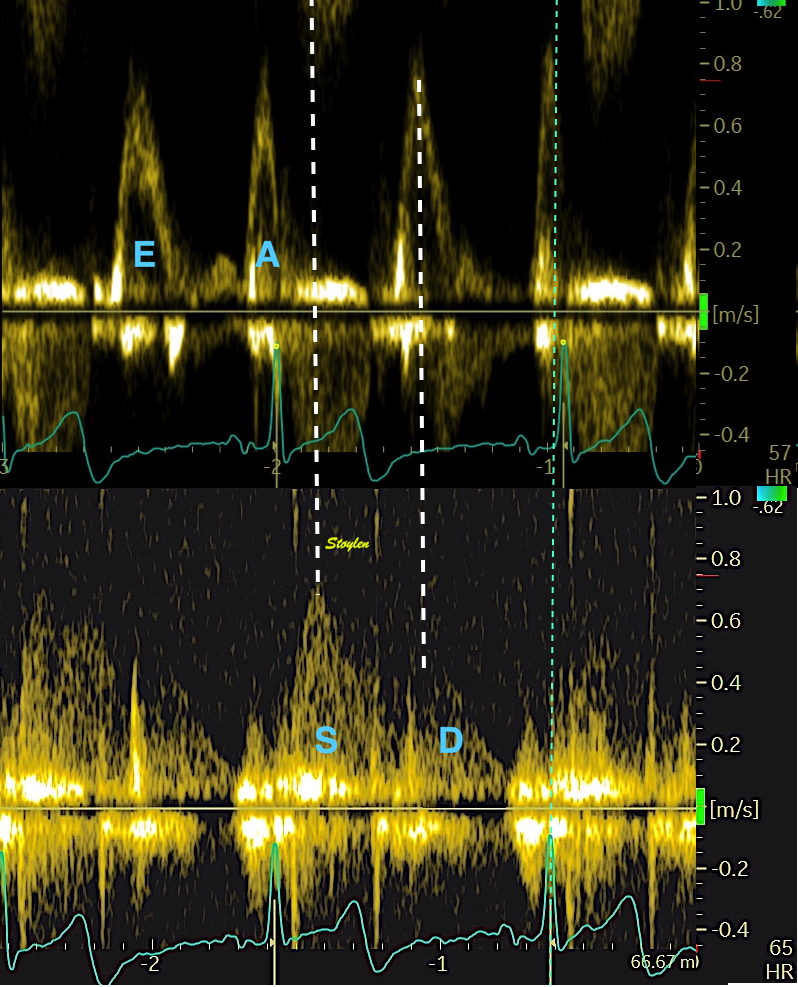

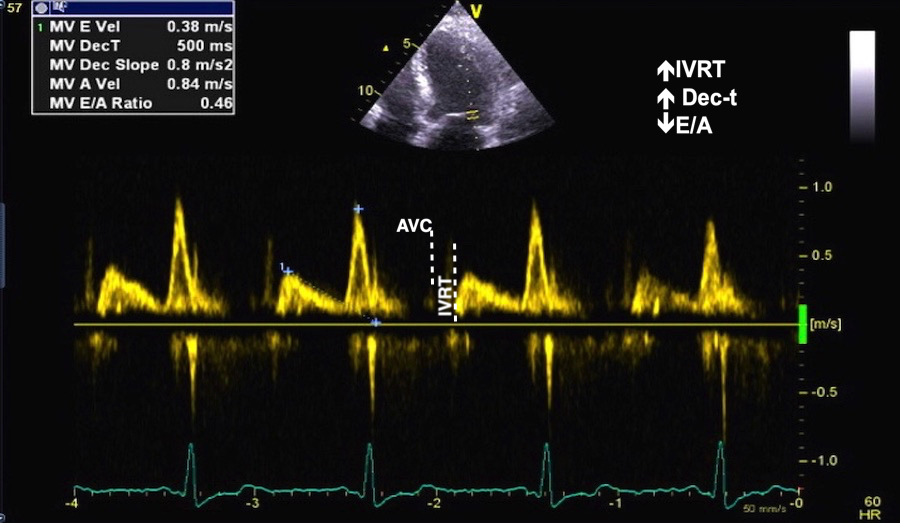

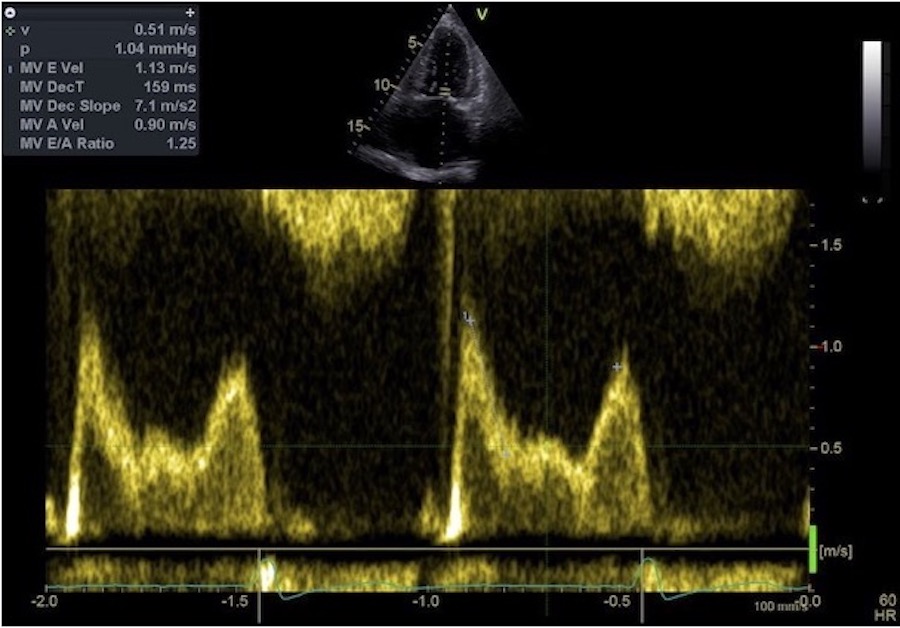

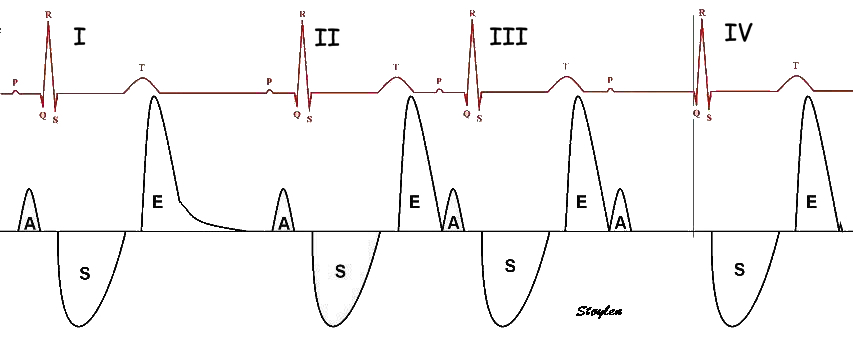

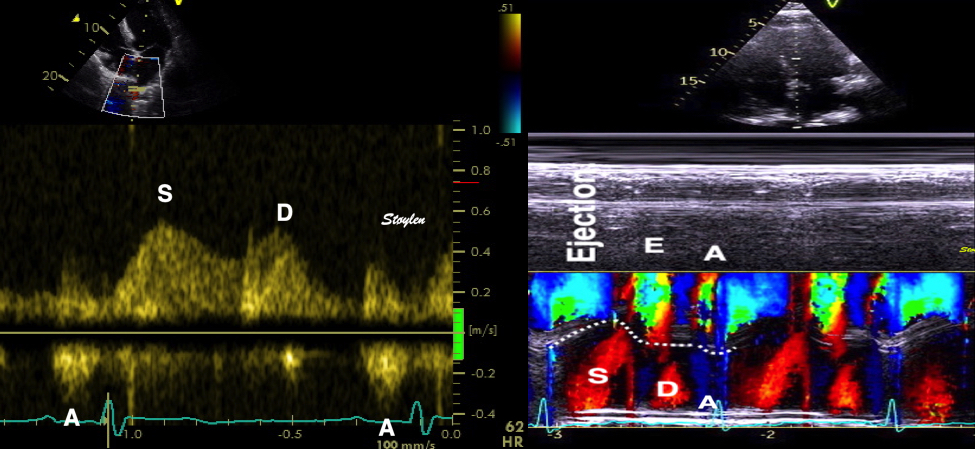

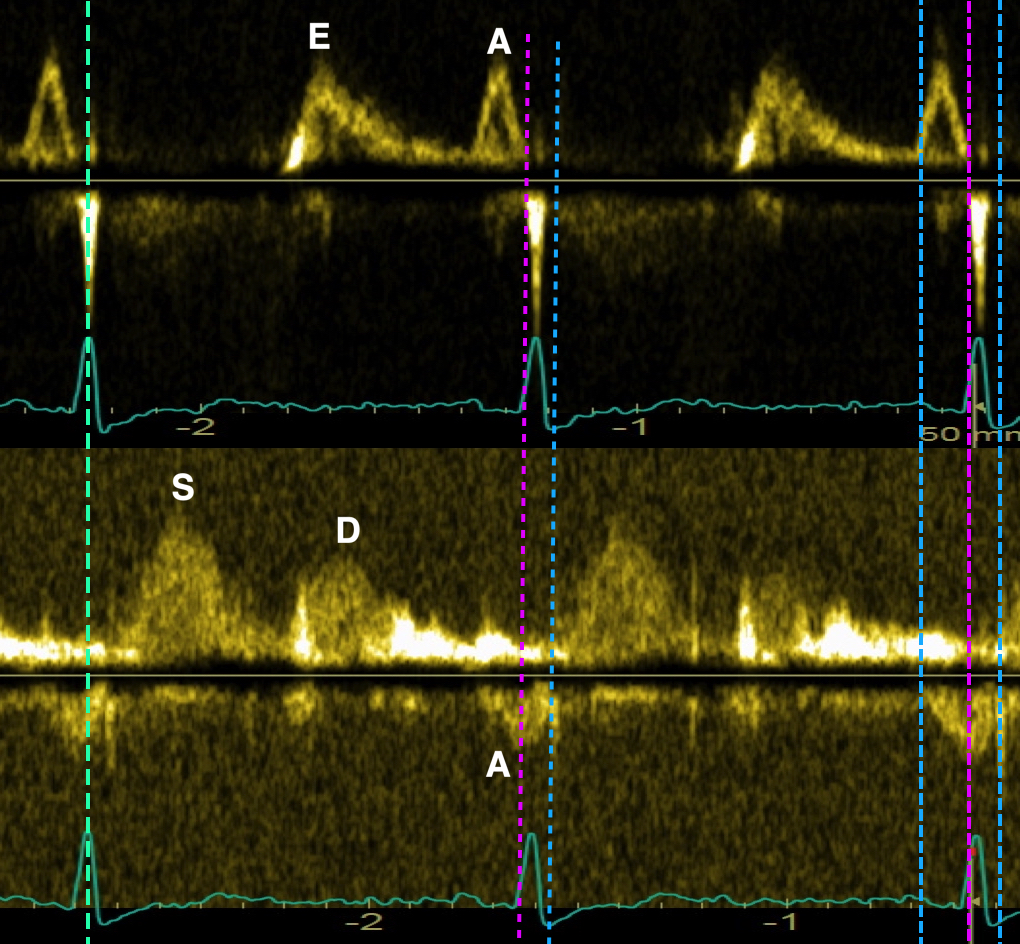

The main intervals of the heart cycle is defined by the valve closures and openings. That means start and end of flow, but with the right positioning of the sample volume /beam, it can also capture the valve closure clicks.

With the right positioning if the sample volume, all left sided valve closures and openings can be registered simultanepously. Valve closures can be seen as clicks, and valve openings can be seen by the start of flow.

Valve opening and closures then can define the main intervals of the heart cycle, IVC, LVET, DFP and IVR.

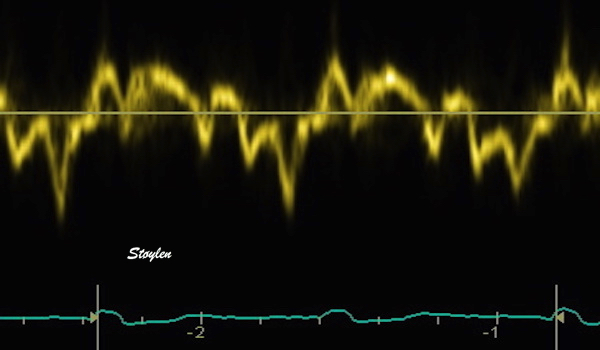

Pulsed wave Doppler with sample volume positioned between the aortic and mitral ostia. Both start and stop of the flows, as well as the valve closure clicks are seen, dividing the heart cycle into the four main phases, ejection, diastolic filling, and between them the isovolumic contraction and relaxation phases..

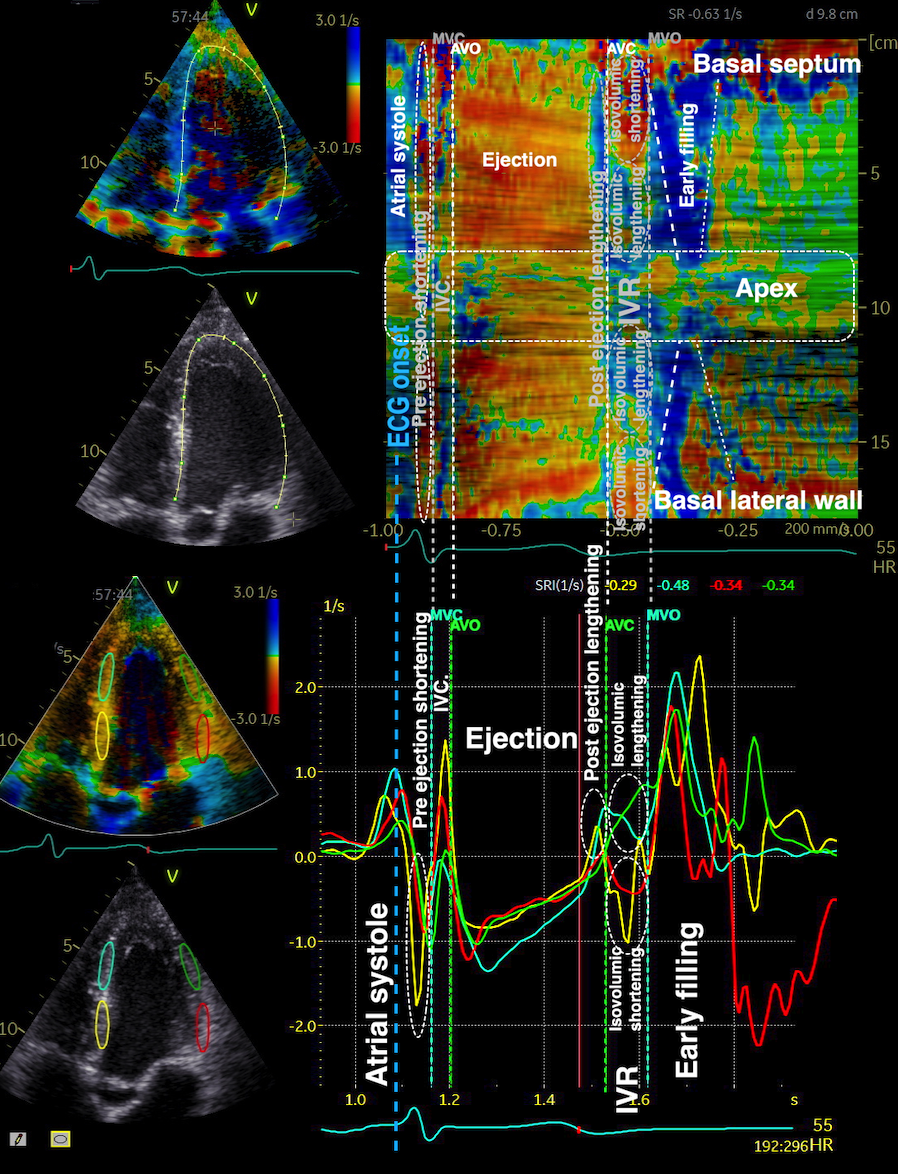

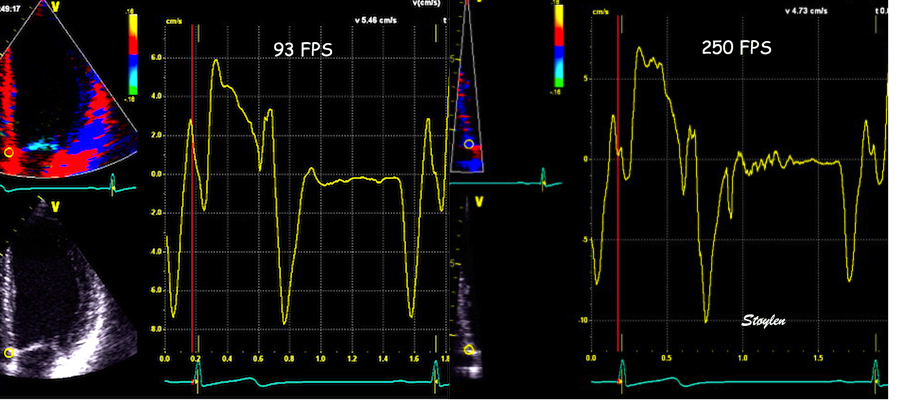

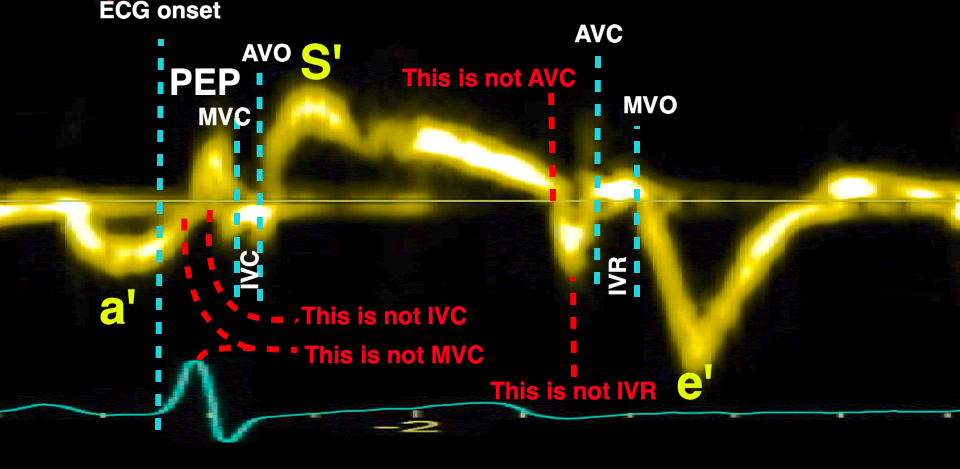

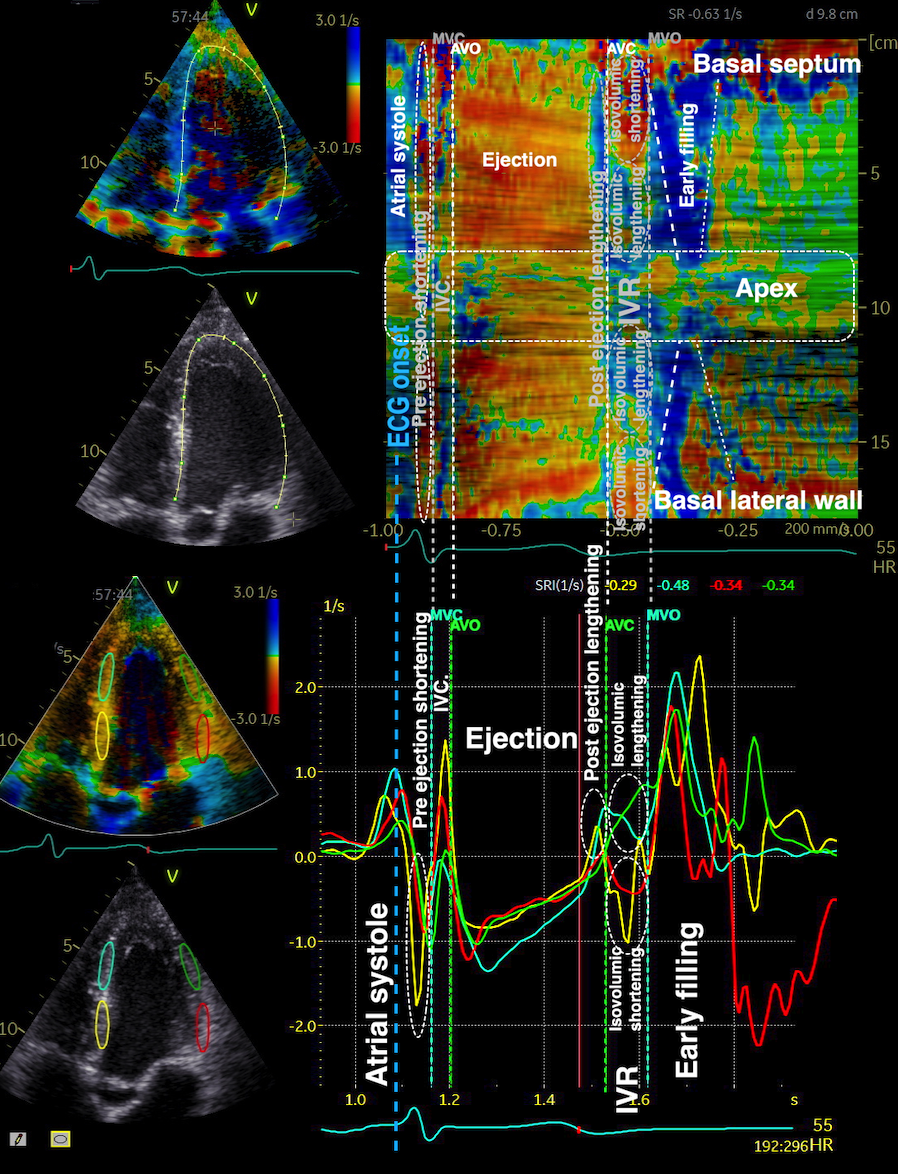

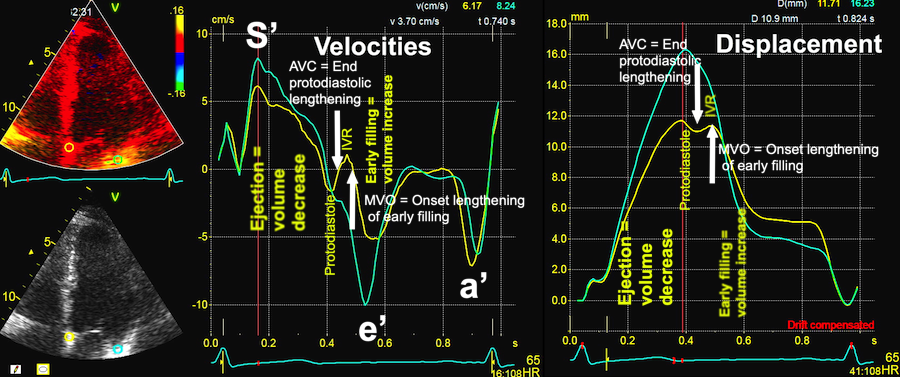

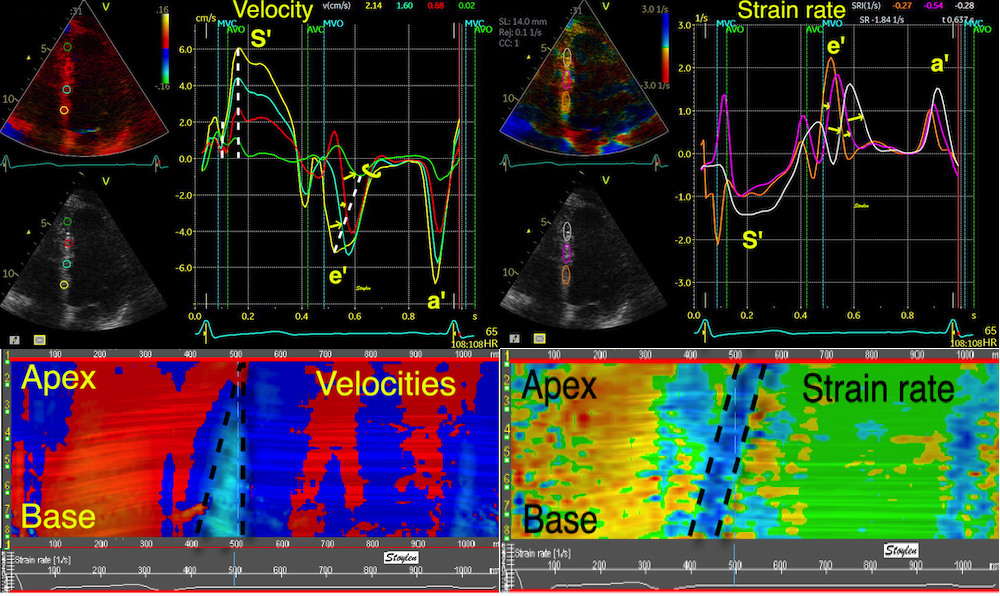

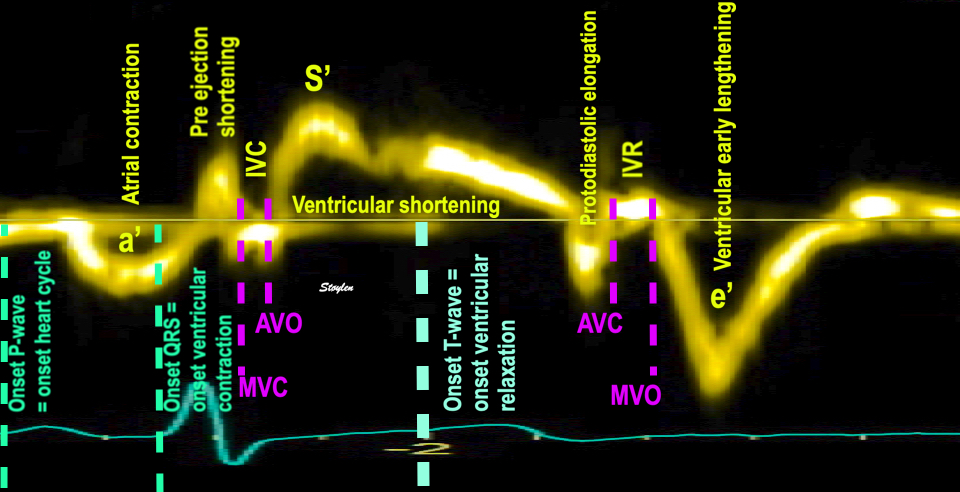

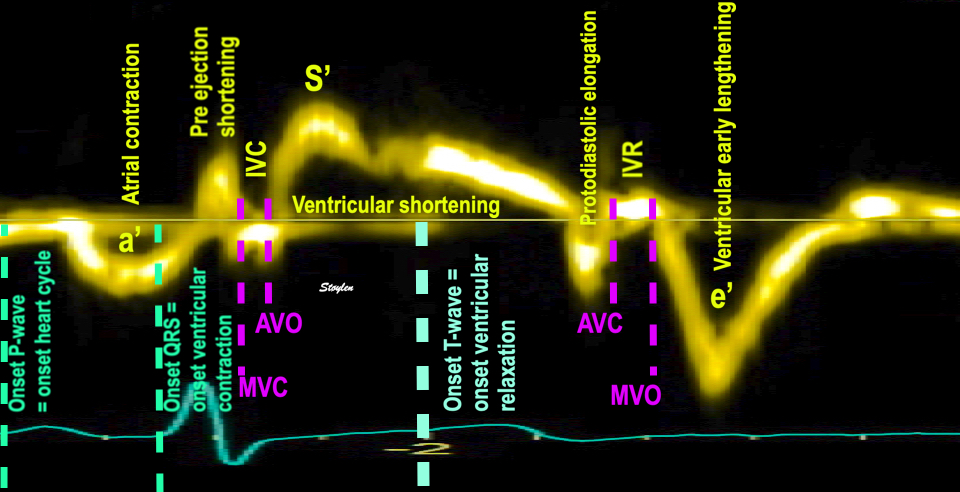

Tissue Doppler and deformation imaging, howebver have given increased understanding of the basic physiology. Looking at the short phases of the heart cycle, like pre ejection, isovolumic relaxation, and early and late diastole, velocity and strain rate are the most useful, as explained here.

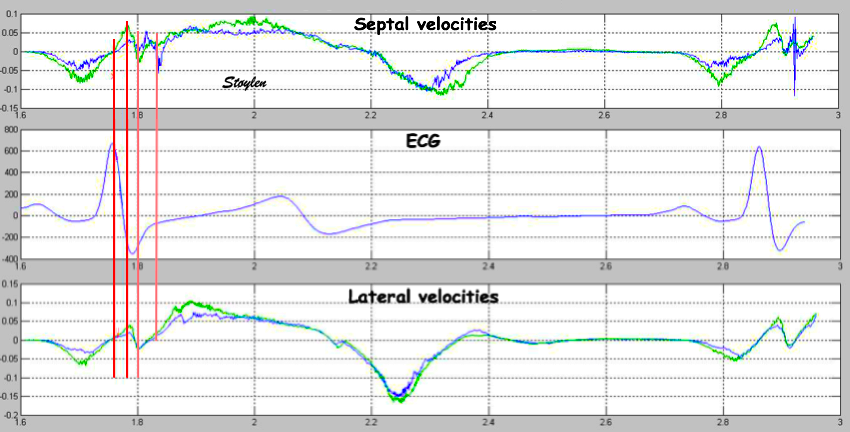

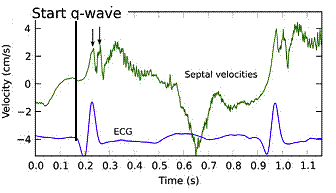

The pre ejection period, is the period from start of ECG, to the AVO (i.e.) the start of ejection (110). It consists of:

The electromechanical activation consists of electrical conduction of the signal from the AV-node through the His' bundle and the anterior and posterior left hemi-bundles. Early experimental and invasive studies seemed to show that there is initial endocardial activation almost simultaneously in mid septum and mid lateral wall, after 0 - 15 ms after onset of ECG (111, 112), but this will be partly concomitant with electromechanical delay at the cellular level. Then, there is electromechanical delay at the cellular level, the action potential generating Calcium influx, again generating release of more calcium form the SR, resulting in onset of cell contraction through actin-myoisin cross bridges. This process takes about 20 - 30 ms (113).

| |

Excitation-tension diagram. After Cordeiro. The Action potential triggers the influx of calcium, which triggers further release of Ca2+from sarcoplasmatic reticulum. Calcium binds to troponin, and allows activated (by ATP) myosin heads to bind to troponin sites on actin (cross bridge forming) and release energy, causing the filaments to slide along each other, as long as there is a high calcium concentration in the cytoplasm. | Image of beating isolated myocyte. The myocyte is treated with an agent that fluoresces in the presence of free calcium in the cytosol. We see that the cell lightens and shortens simultaneously; stimulation causes an increase in free calcium (released mainly from the sarcoplasmatic reticulum), causing the cell to become lighter. The free calcium is the trigger for the binding of ATP, and the formation of activated cross bridges between actin and myosin, and the subsequent rotation and release, which leads to the buildup of tension in, or shortening of the cell. Image courtesy of Ph.D. Tomas Stølen, cardiac exercise research group (CERG), |

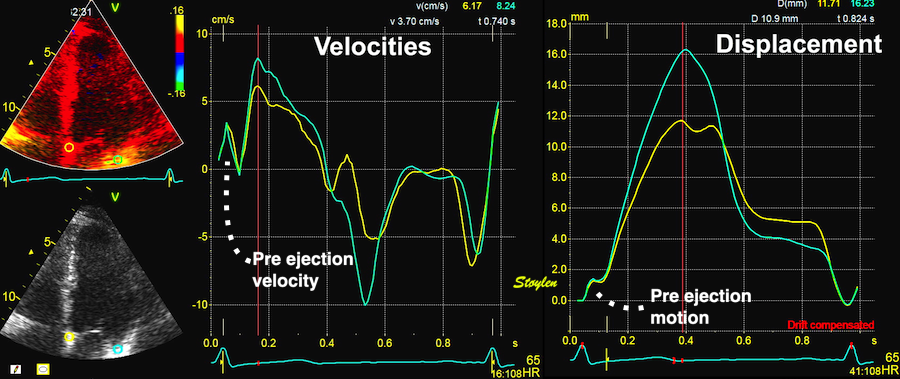

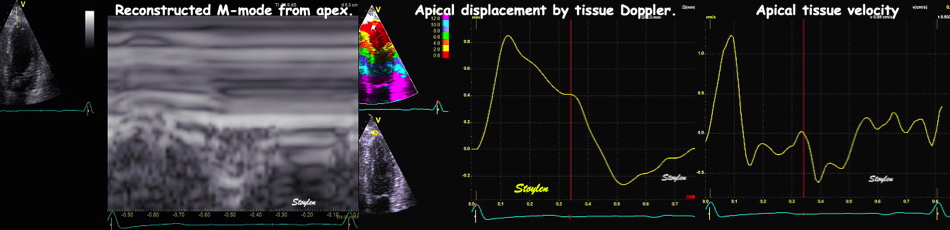

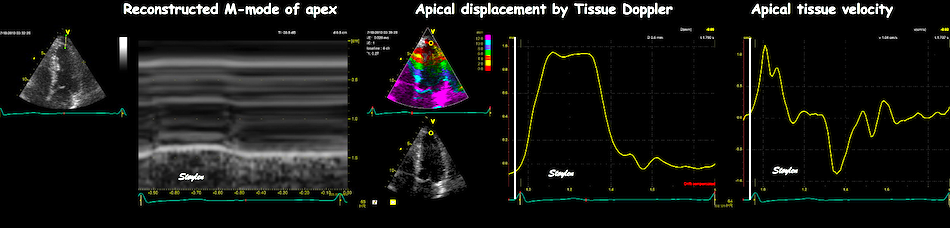

With tissue Doppler, it became evident that before ejection, a short positive velocity spike was visible. It was visible in both septum and the lateral wall (72), and it corresponded to a very small pre ejection apical displacement as seen by M-mode and displacement traces.

Pre ejection velocity is seen as a small, positive velocity spike before the main motion of the ejection phase, and, correspondingly, a small apiucal motion that can be discerned both in the M.mode and displacement traces. This pre ejectiopn motion is present both in the septum and the lateral wall.

Pre ejection spike can be seen to be lower than peak ejection in most instances | ||

|

|

|

-by spectral tissue Doppler | by colour tissue Doppler | and by speckle tracking. |

The timing of this event has been shown to precede MVC (72).

The pre ejection spike thus occurs BEFORE MVC, as seen here (valve openings and closures from Doppler flow - different cycles). | MVC is concomitant with the stop of pre ejection apical motion. |

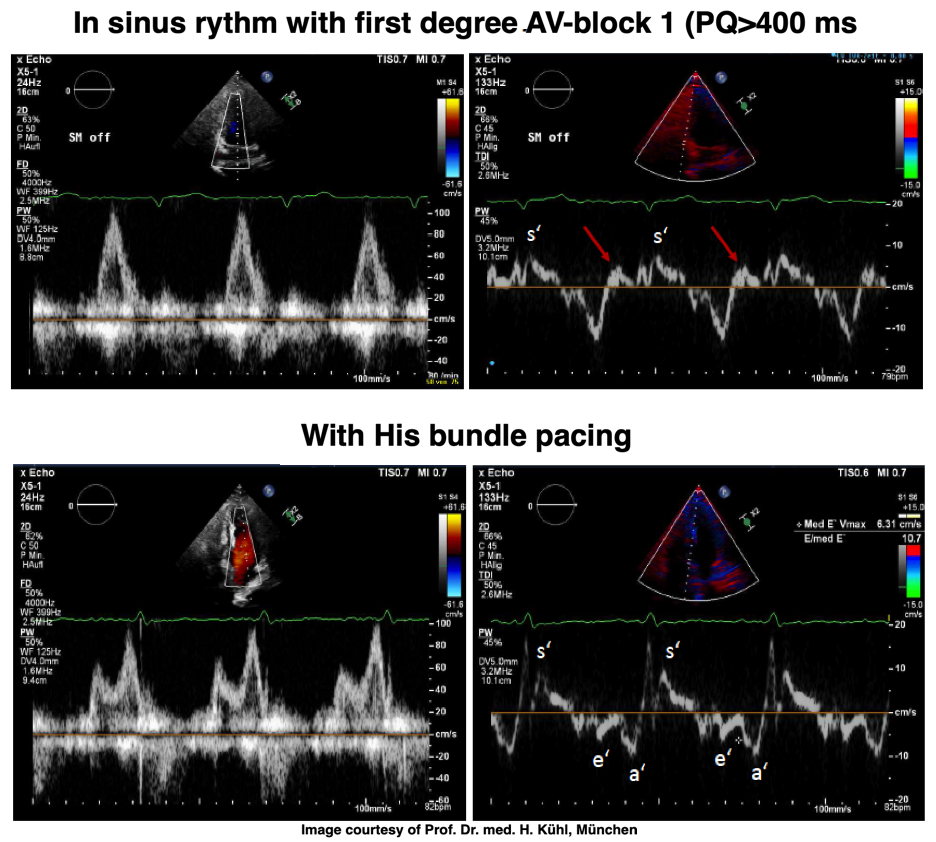

It has been suggested to be passive rebound after atrial contraction. This has been suggested, but the pre ejection spike is seen also in atrial fibrillation (114, 117). Rebound after atrial relaxation is present, though, and can be demonstrated, both with and without (as in AV-block) succeeding ventricular contraction, but the timing in relation to the following systole depends on the PQ time. What we see, is that after the a' wave, there may be some rebound oscillations visible in long PQ time or dropped beats, which normally would be dampened by the stiffening of the ventricular myocardium by the onset of contraction.

|

|

|

Ultra high frame rate tissue Doppler from the base of the septum a subject with atrial fibrillation. Even with no atrial activity, there is pre ejection velocity spikes, showing them to be ventricular in origin. | Ultra high frame rate tissue Doppler from the base of the septum a subject with 1st degree AV block. (This is a highly trained, healthy subject, the AV block is physiological)Three spikes are seen before ejection (arrows). Here, the initial spike must be atrial recoil, coming before start of the the QRS, it cannot be ventricular i origin. Even the second spike may be atrial, or a fusion of an atrial bounce and ventricular contraction. | Ultra high frame rate tissue Doppler from the base of the septum a subject with 2nd degree AV block, as seen by the second P-wave following the first heartbeat, with no QRS nor ejection velocities. The atrial recoil can be seen as three velocity spikes (arrows), indicating that the mitral ring bounces. However, this is in a situation without LV myocardial tension. At start of the first heart cycle, there may be some fusion between atrial recoil and ventricular contraction as seen by the timing. |

If PQ time is very long, the atrial rebound and pre ejection spikes become separated:

PW Doppler of mitral flow and tissue Doppler from a patient with a PQ time > 400 ms. This pushes the A wave forward to the preceding heartbeat, causing EA fusion as explained elsewhere, but increases the interval between atrial and ventricular systole. After the a' wave in tissure Doppler there is a clear positive wave, that can be seen before the normal pre ejection spike, and may represent a rebound from atrial contraction. With HIS pacing on, the PQ-time is normalised, and both EA fusion and the rebound wave are abolished, the latter may be dampening with the onset of ventricular myocardial contraction (stiffening). The normal pre ejection spike, however, is enhanced. Images courtesy of Prof. Dr. med. H. Kühl, Chefarzt, Klinik für Kardiologie und Internistische Intensivmedizin, Klinikum Harlaching, München.

With ultra high frame rate (1200 FPS) ultrasound, (HFR IQ data), where both MV M-mode and TDI was reconstructed from the same cycle, and the velocity spikes were comp+ared to a reconstructed MV M-mode, MVC was seen to come after the pre ejection spike. In a study of ten healthy subjects, time intervals from start of ECG to start of the initial pre ejection velocity spike in the septum was 22.7 ms, and from this to MVC was 29.6 ms. Findings were very consistent with the electrophysiologic intervals, indicating that the pre ejection spike was active contraction, but also that the onset of active contraction occurred before MVC (114).

Ultra high frame rate tissue Doppler (about 1200 FPS) from the base of the septum a normal subject. The timing is evident, with ECG starting first, then the pre ejection velocity spike starting about 23 ms later, and then the mitral valve closure about 30 ms after this. This recording is from the septum, and as can be seen, in the septum there is a second spike before ejection starts. It can be seen to repeat from beat to beat. This was not present in the lateral wall.

The findings were later confirmed by a simple study with transfer of valve motions from Doppler flow recordings to tissue Doppler (72). This method is slightly less accurate, both because of the lower frame rate, and as there is some heart rate variability when valve clicks are transferred from other cycles.

Valve closures by valve clicks, and openings by onset of Doppler flow, to the right transferred to the analysis window for tissue Doppler to the left. Relations between timing of tissue Doppler motions and valve motions are typical: Q to onset pre ejection spike (EMD) was about 25 ms, duration of the pre ejection spike about 50 ms, and MVC to end pre ejection spike (ms) about 10 ms.

However the findings were close; Pre ejection spike:

Thus, pre ejection spike is not isovolumic contraction. This rather absurd explanation is a contradiction in terms, as it is present both in the septum and lateral wall, it must necessarily correspond to a volume reduction, which means that the phase is not isovolumic at all. Still, there were some publications on both isovolumic velocity and isovolumic acceleration as contractility measures based on this erroneous concept, as discussed below.

The pre ejection shortening has so short duration, that it is most readily demonstrated by strain rate rather than strain.

Pre ejection strain rate, active contraction can be seen to be simultaneous in both walls and in both basal and apical level, and to occur before MVC.

In 1973 by phonocardiography (115), and in 1978 by radioopaque markers (116) the ventriculoatrial crossover was demonstrated to occur ca 40 ms before MVC, demonstrationg that this is the onset of thesion buildup, i.e. that this pre ejection motion is active contraction.

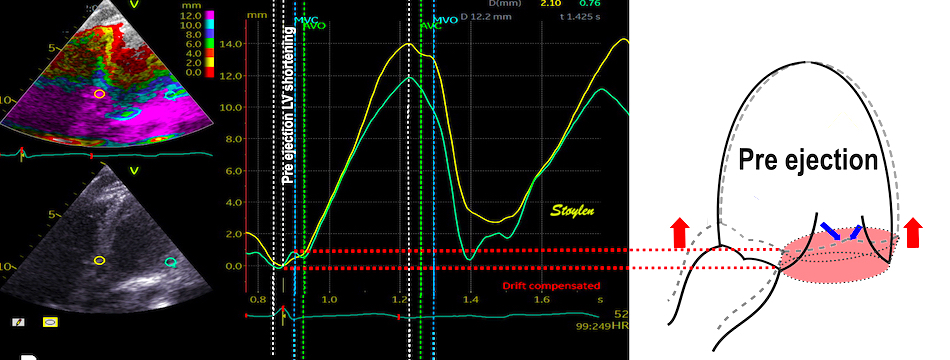

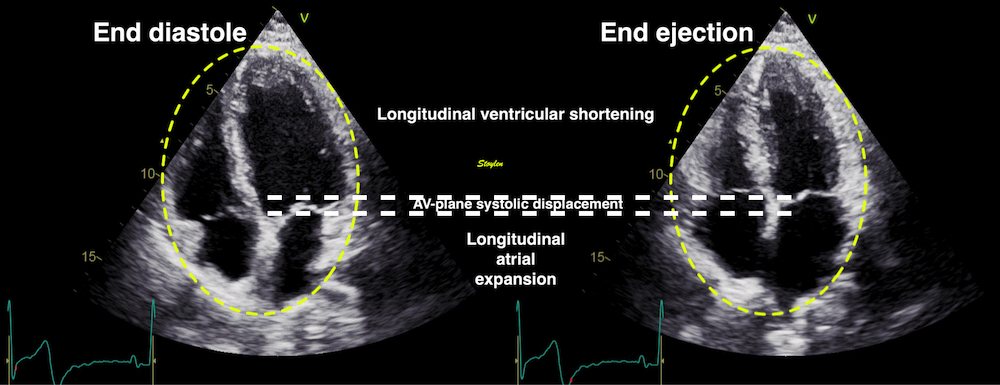

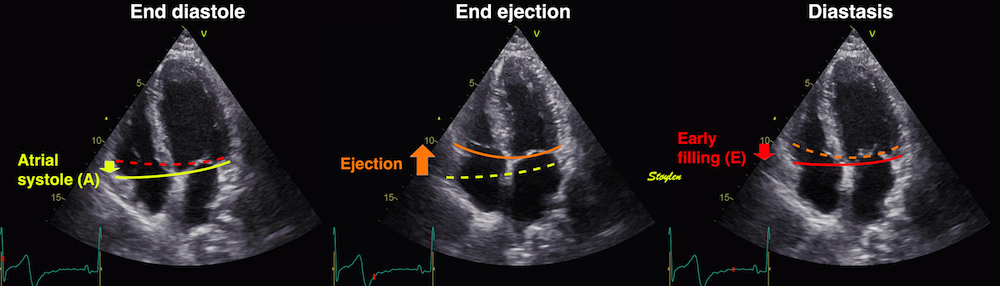

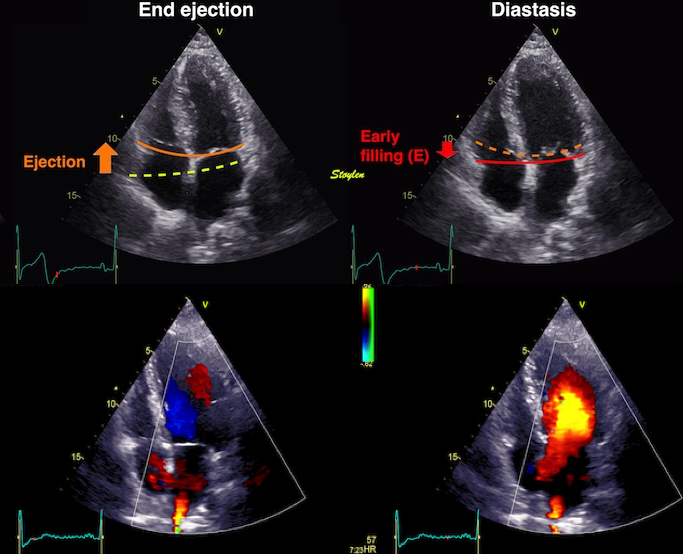

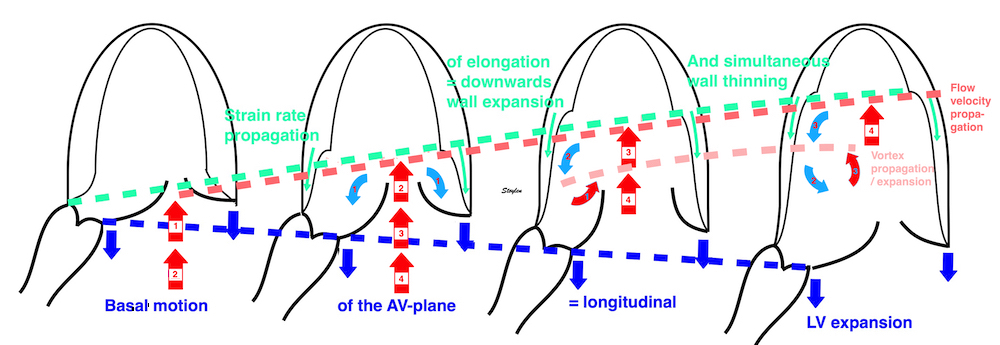

The finding of mitral ring motion in both walls, must mean that this is a real volume reduction of the LV (72), again indicating that this is active contraction. Even without mitral flow, the displacement of the mitral ostium will exclude (atrialize) a small volume from the ventricle:

The apical ring motion is equivalent to a longitudinal shortening, as shown by the strain rate above, and thus a volume reduction, not by flow, but by exclusion of a small volume by the ring motion while the mitral valve is still open.The ring motion will also displace the mitral leaflets towards the base and middle, as they move in the blood. However, the main mechanism for MVC seems to be intraventricular flow as discussed later.

This volume reduction before MVC was also demonstrated experimentally in dogs by conduction catheter, and was shown to be ca 4.2% of EDV (117).

The presence in both septum and lateral wall, and the fact that both walls show negative strain rate (72), as well as the concordance with the known electrophysiology (111 - 113), makes it also very probable that the pre ejection spike is active contraction, and shows the true electromechanical activation, by the left anterior and left posterior bundles.

The pre ejection motion, is thus a contraction, representing a shortening before MVC, meaning at a load of atrial pressure, i.e. near unloaded. Peak pre ejection (72):

Peak pre ejection | Septal | Lateral |

Velocity (cm/s) | 3.59 (1.56) | 3.55 (1.58) |

Strain rate (s-1) | -0.77 (0.61) | -0.66 (0.38) |

Standard deviations in parentheses.

Could this be a measure of contractility?

|

|

Isotonic isometric twitches. The peak tension development is slightly after onset of contraction, | Pre ejection velocity spike occurs before MVC, and thus occurs at the level of atrial pressure, as close to an unloaded situation as one gets. |

Although some papers have been published with "isovolumic acceleration" as contractility measure, it isn't.

Logically, the MVC should be at the abrupt stop of the pre ejection displacement, i.e. where the velocity trace crosses the zero line after the spike due to the sudden increase in resistance to movement at the closure ov the valve as the cusps stay in the stationary blood stream :

Blown up image of the pre ejection period, displacement to the left, velocity to the right. The logical time for the MVC is when the apical displacement stops abruptly. This is equivalent with the velocity spike retuning to zero, as can be seen with the relation to ECG. As we see, there is a slight initial velocity, and then a break point in the velocity curve, concomitant with the onset of shortening as seen by the displacement curve, corrsponding to the second spike as seen below.

Thus it's the MVC that is actually terminating the pre ejection longitudinal motion /volume reduction.

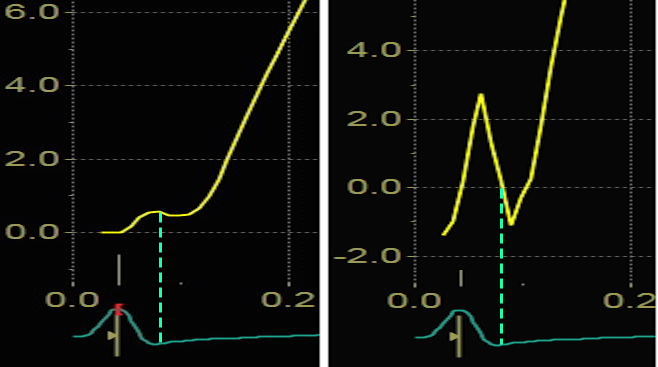

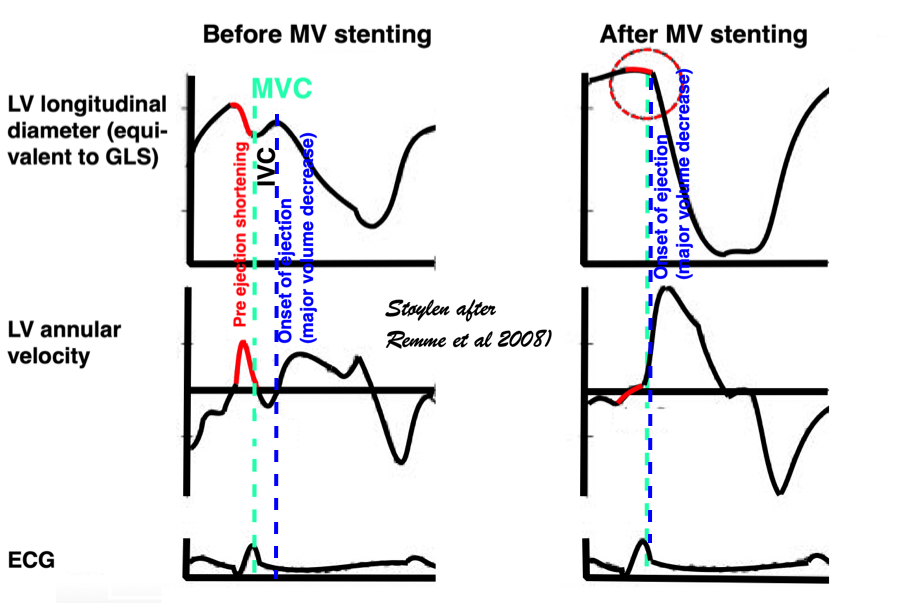

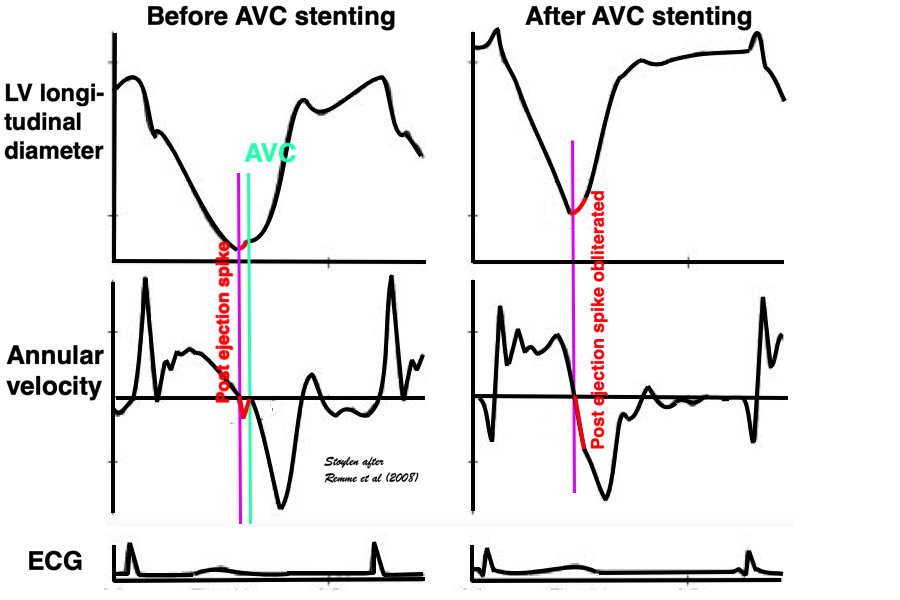

An experimental study, where the MV was stented open, confirmed this, showing that while shortening started at the same time in the stented situation, the motion (and strain) continued directly into the ejection phase, without the abrupt stop after pre ejection velocity, showing that the start of pre ejection shortening is the true electromechanic activation, while it is the MVC itself that terminates the pre ejection spike (117):

Representation of the findings in the experimental study, showing that as onset of contraction results in shortening, this is interrupted by MVC (onset of IVC), and the velocity spike returns to zero. When mitral valve is stented, this results in a smooth non-interrupted transition to ejection velocities, so the pre ejection strain and velocity (red part of curves) are nearly obliterated, and the onset of the ejection phase the major volume rediction seen by the major downward stroke of the strain curve and the upward stroke of the velocity curve) is starting at the point of the previous MVC, thus the ejection phase now starts at the onset of what was IVC without the stent..

Thus, the pre ejection velocity or strain rate spike is not in accordance with the physiological expectations, and peak protosystolic velocity is not a close measure of maximum unloaded shortening velocity / rate.

The reasons for this may be that as an event of very short duration;

The main point is that the peak protosystolic velocity or acceleration is not a contractility measure.

It has been suggested that the pre ejection annular motion is the mechanism for MV closure (117), the apical motion of the annulus on the stationary blood forcing the valves in the basal direction. However, the basal mitral leaflet motion is greater than the apical motion of the annulus, so this is insufficient to explain the closure. In addition, this hypothesis doesn't take the intraventricular flow into consideration.

During pre ejection, concomitant with the QRS, there is an intraventricular vortex that stems from the early and late filling vortices.

At the end of diastolic filling, the flow in the ventricle consists of a vortex formed by merger of the vortices from the early and late filling phases as discussed later. This vortex is counterclockwise seen in the traditional 4-chamber view, with basally directed flow along the septum, and apically directed flow along the lateral wall (118, 119).

|

|

|

Septal colour M-mode showing basally directed flow along the septum during PEP. It can be seen to start at the beginning of MV closure, and is directed towards the anterior mitral leaflet. | Vector flow imaging, showing the intraventricular counterclockwise vortex during pre ejection, already before MVC. The finding is consistent with the colour M-mode findings. Image courtesy of Annichen S Daae. | Lateral colour M-mode showing apically directed flow along the lateral wall during PEP. |

The vortex is the end result of the diastolic filling (118), as discussed later. The basally directed flow along the septum will contribute to two mechanisms:

The true isovolumic contraction time (IVC) is defined from MVC to AVO, and MVC is defined by the true valve closure, while the AVO is marked by the start of LVOT flow:

As shown above, MVC is at the end of pre ejection tissue velocity:

Thus, in this phase there is no volume change, and, hence, no deformation. This phase it on the other hand, the period of most rapid pressure rise, peak dP/dt, which occurs during IVC, close to the AVC (121). This represents the most rapid rate of force development (RFD). Peak dP/dt can be measured from flow velocity if there is a small MR (122).

|

|

Peak rate of pressure rise, which is the closes correlate to the rate of force/tension development. This occurs during IVC | dP/dt can be measured by the velocity increase, if there is a small MR, too small for generating a pressureincrease in the atrium. It is customary measured between 1 and 3 m/s, which is equivalent to a pressure increase of 32 mmHg, and the dP/dt becomes a function of the time interval between then, and is used as proxy for peak dP/dt |

As it occurs before AVO, it is not afterload dependent (121), and is a useful invasive index of contractility. However, as seen fom the length force relation above, this maximal force measure is not preload independent.

During pre ejection, the vortex is seen to persist after MVC, and the septal part aligns with left ventricular outflow (118). This adds momentum and kinetic energy to the ejection flow.

Septal colour M-mode showing basally directed flow along the septum during PEP. It continues until AVO, adding momentum to the ejection, while the lateral, apically directed part of the vortex seem to attenuate.

This means there is a momentum towards the base, aligned with the LVOT even before the AVO. The velocity momentum is equivalent to a partial pressure gradient, and thus contributes to a small reduction in afterload, facilitating the ejection, by conservation of kinetic energy from filling in the vortex.

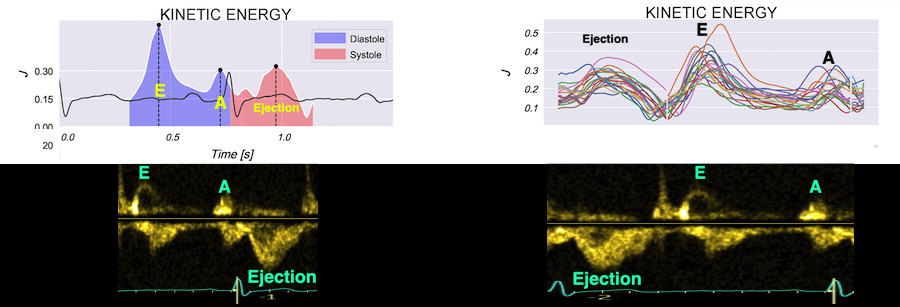

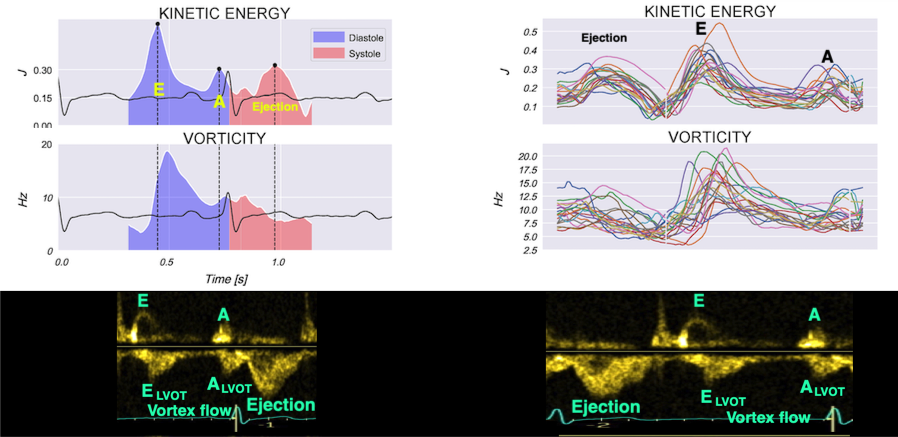

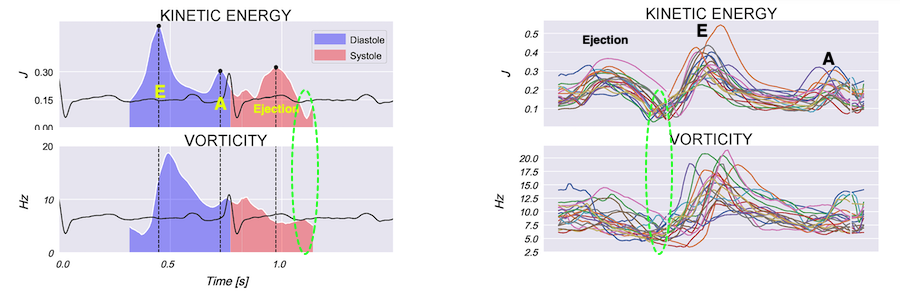

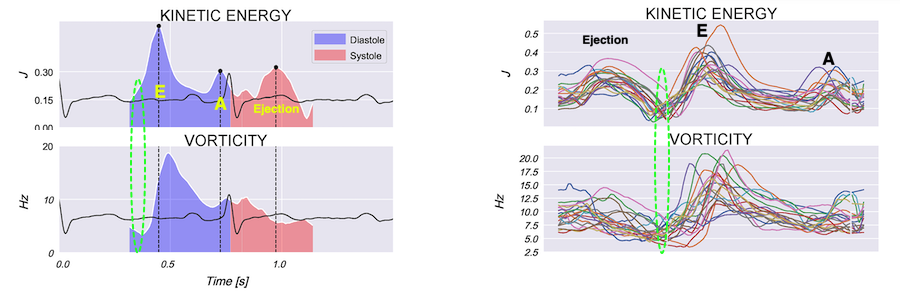

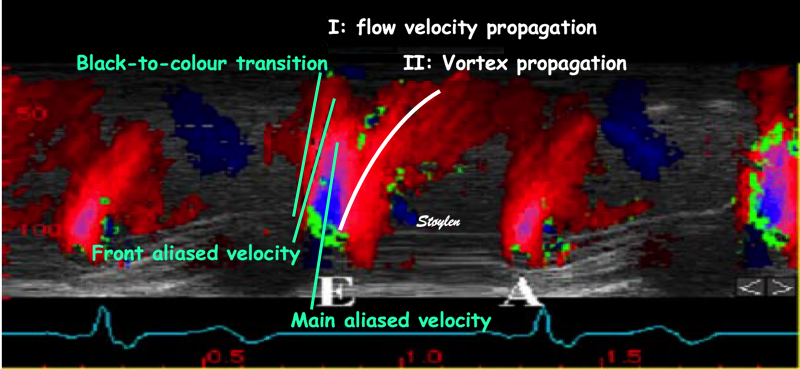

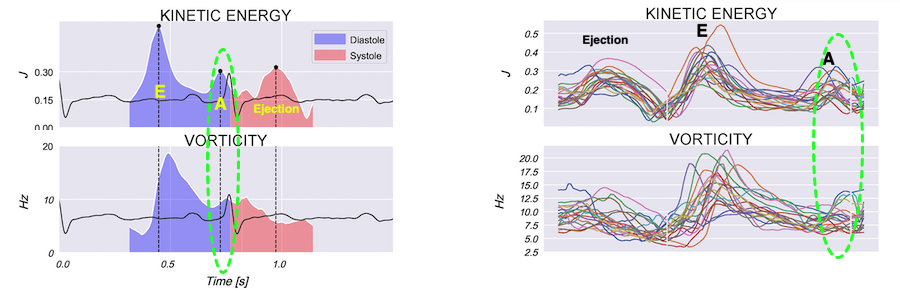

Vorticity is a measure of the rotation of the blood around each point in the image at one timepoint in the cardiac cycle and is a measure of the complexity of the blood flow. The unit of vorticity is Hz. The time trace of vorticity is found by averaging the region of interest (the LV). In our application, this is calculated by the curl or momentum of

the blood velocity field.by the formula:

As it is measured over a 2D area, it may differ from volume based calculations. The main interest is in the changes in vorticity during the heart cycle, and the relation to the kinetic energy.

Vorticity plot, showing that vorticity peaks during pre ejection and declines during ejection, despite the ejection showing higher kinetic energy. A reasonable assumption is that kinetic energy is transferred from the vortex to kinetic energy in ejection flow. Images courtesy of Morten S Wigen.

Vorticity is a quantitative measure. Mean vorticity was found in our study to be 10.0 Hz (9.2 - 11.1) in diastole and 8.6 (7.8 - 10.1) in systole (118). Again vorticity will probably differ between applications. The qualitative description can be seen from the 2D vector flow above, reasoned from the colur flow M-mode above, and even seen from the pulsed wave Doppler flow:

|

|

|

The vortex is present in diastasis, but increases during late filling. Image courtesy of Annichen S Daae | pw Doppler, showing that both early and late inflow are diverted into the LVOT by a slight delay, which visualises the vortices related to the inflow. | This diversion is related to the basal motion of the AV-plane, as seen by the colour M-mode. |

Thus, qualitative clues to the vorticity are present. The presence of vortices in large parts of the heaqrt cucle, is assumed to conserve kinetic energy form one phase, to be utilised in the next, as discussed under the different phases.

It is evident that the kinetic energy is closely related to flow velocity.

The energy unit is J/m, as we do an integration of 2 dimensions only. As we see, there is a close correspondance between the velocity curves and the energy traces.

The kinetic energy per volume of blood is given by the formula:

![]()

where is the density of blood and v is the flow velocity. Blood speckle tracking allows for estimating the total energy, not only the velocity components along the ultrasound beam as in Doppler. But we do not have full volumetric data, we integrate over a 2-D region (the left ventricle), with the resulting unit of J/m.

![]()

The mean energy is found in our study was 0.21 (0.18 - 0.25) J/m in systole and 0.20 (0.17 - 0.23) J/m (118). The values will differ between applications, as the spatial algorithms will vary, and the unit J/m, which is the 2D measure differs from the true volume measure.

When inflowing blood is diverted into a vortex, the kinetic energy is conserved, to the degree that velocity is maintained. The vorticity is thus a measure of energy conservation. Peak vorticity can be seen to coincide with, but slightly later than the peak vortex inflow in LVOT:

There is some kinetic energy at the onset of early filling, which is expected from the mechanics of the IVR. Vorticity at end ejection IVR is at a minimum, although not absolutely zero, some vorticity generated at end ejection is still present. As we see, there is a close correspondance between the velocity curves and the energy traces, and between the vorticity curves and the vortex inflow in LVOT.

Flow velocity depends on the pressure gradients.

Pressure gradients can be estimated from the flow velocity field:

![]()

![]()

is the density of blood, about 1060 kg/m3 , (vx, vy) is the velocity vector and

is the blood viscosity; about 0.004 Pa/s.

Intraventricular pressure gradients were calculated along a manually defined path from base to apex (118):

![]()

Of course, calculating pressure gradients from flow, doesn't explain flow pattern, as the pressure gradients are derived from the flow pattern at the outset. Thus, thie explanation would be tautological, it is just a description of flow velocity in terms of pressure.

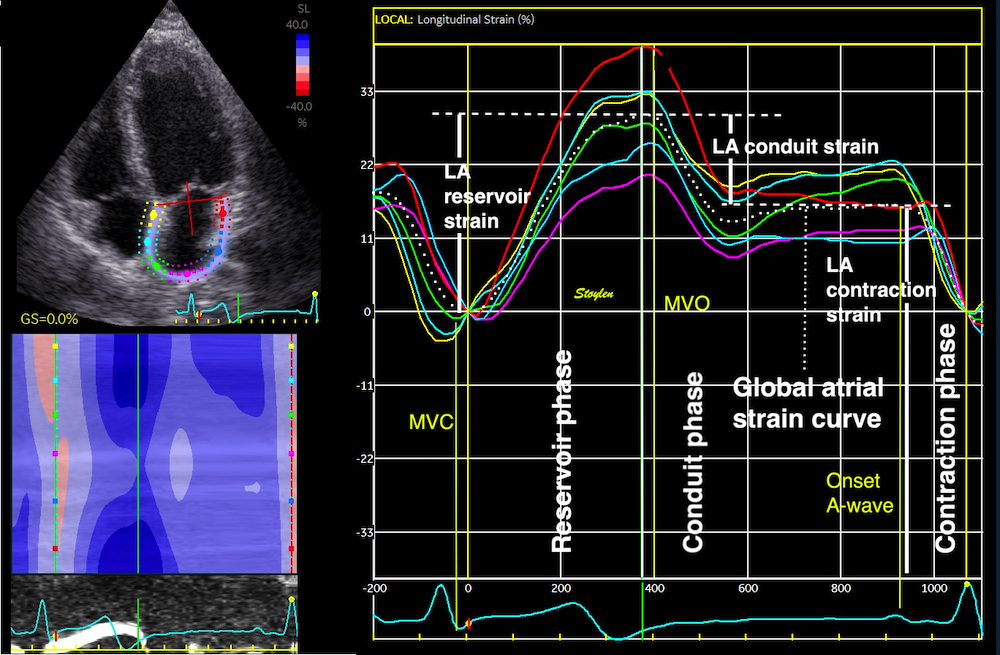

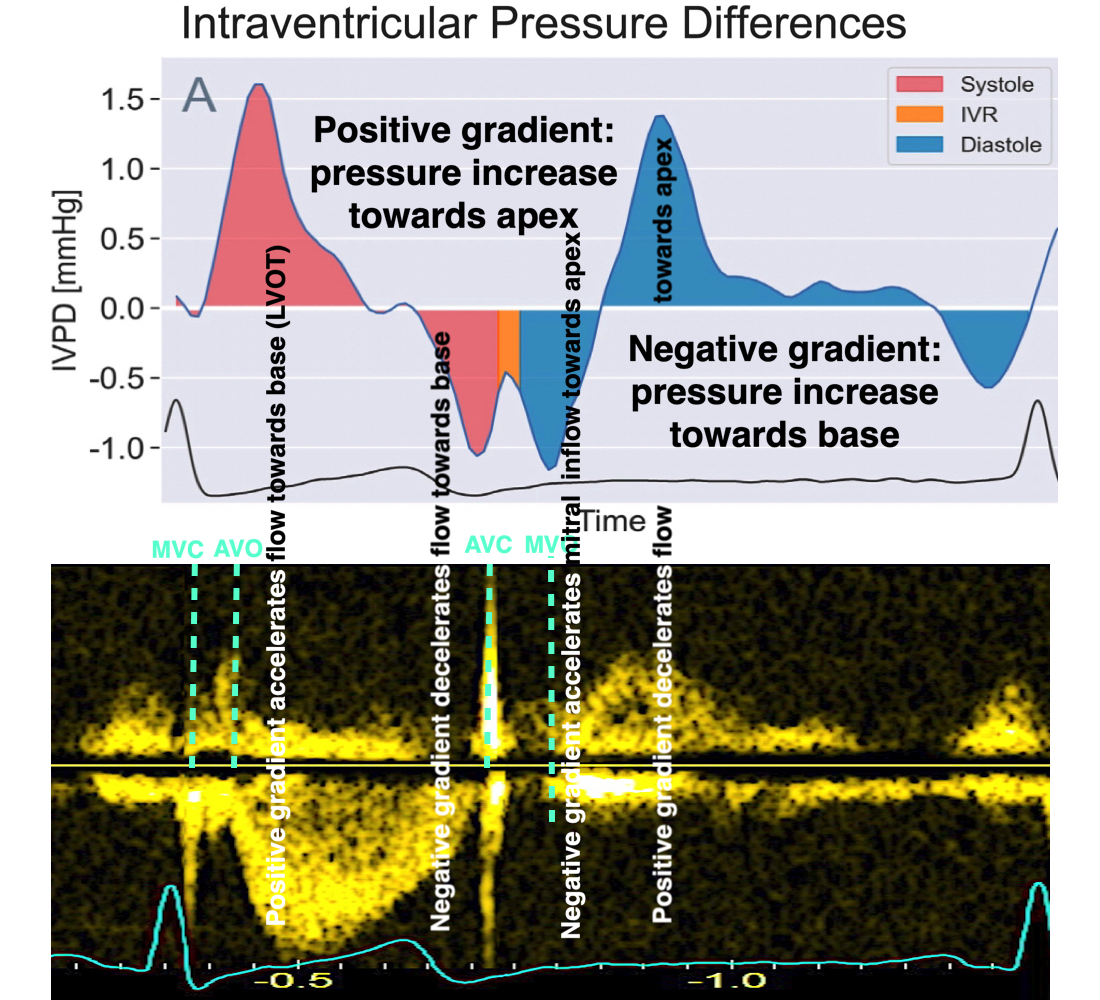

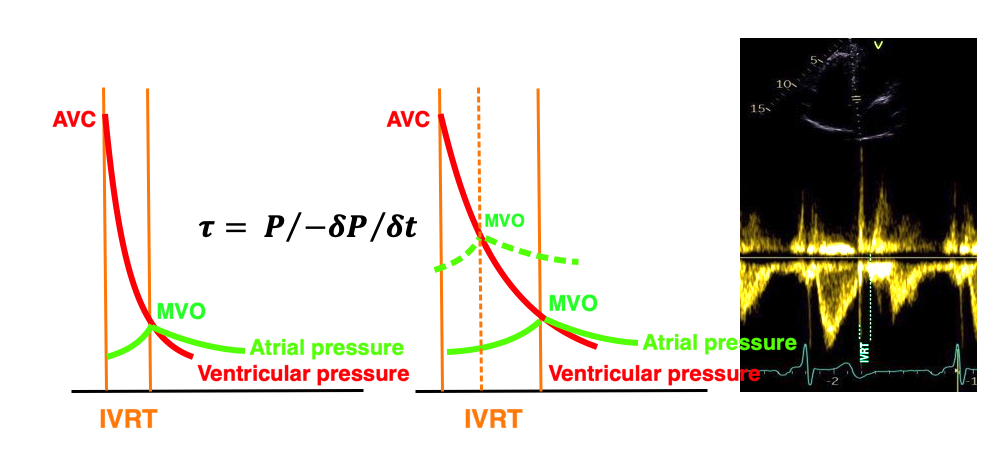

Positive intraventricular pressure gradients (pressure increase) towards the apex will accelerate blood flow towards the base/LVOT (ejection), and decelerate blood flow towards the apex (inflow). Negative intraventricular pressure gradients (pressure decrease) towards the apex will accelerate blood flow towards the apex (inflow) and decelerate blood flow towards the base/LVOT (ejection). There is a correspondence between velocity, as velocity increases, pressure falls, as velocity decreases, pressure increases.